CHAPTER 8 Principles of surgery and management of intraoperative complications

Opening and Closing the Abdomen

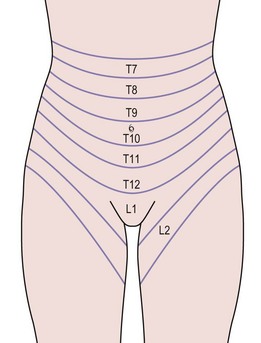

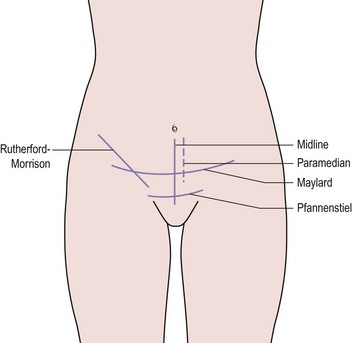

The layers of the anterior abdominal wall include skin, subcutaneous fat, rectus sheath and oblique abdominal muscles, transversalis fascia and peritoneum. Within these structures lie segmental arteries, veins and nerves that supply the dermatomes and myotomes, and also the epigastric vessels (Figure 8.1). Abdominal incisions have been developed that preserve function as well as possible and which heal rapidly with good strength. Commonly used incisions are shown in Figure 8.2.

It should not be forgotten that inappropriate wound closure technique can increase the risk of pulmonary complications and death (Niggebrugge et al 1999). While some surgeons prefer to use electrocautery rather than a cold scalpel to open the wound, there seems to be no difference in the early or late complications in midline incisions (Franchi et al 2001).

Incisions

The vertical midline incision avoids all major nerves, vessels and muscles by dividing the rectus sheath. It gives good access to the whole of the abdomen except the subdiaphragmatic areas, and is a very fast incision to make. Its principal drawback is that it heals slowly and suffers from a high incidence of wound dehiscence and incisional hernia. The development of improved sutures and technique has dramatically reduced these complications. A midline incision should always be closed using the ‘mass closure’ technique. This involves 1-cm-deep bites of the rectus muscle and peritoneum in a continuous closure, with sutures placed 1 cm apart. The suture material used does not affect the rates of dehiscence or infection, but incisional hernia is more common if braided absorbable material is used (Rucinski et al 2001). The same meta-analysis showed that incision pain and suture sinus formation are more common after non-absorbable material is inserted. Absorbable monofilament used in a continuous mass closure gave the best results.

The Maylard incision involves dividing all layers in the line of the skin incision and also divides the inferior epigastric vessels. The rectus sheath is not separated from the muscle and closure is in layers, leaving the muscle to be drawn together by the sheath. This incision provides improved access to the pelvic side wall when compared with the Pfannenstiel incision, and is useful for oncological surgery. Many centres now use this incision or a Pfannenstiel incision for radical hysterectomy (Orr et al 1995, Scribner et al 2001).

Drains

Drains are used either therapeutically, to remove pus, infected material and products from an abscess, or to prevent accumulation of blood, pus, urine, lymph, bile or intestinal secretions. There is little evidence to support the use of prophylactic drains. In abdominal incisions, drains have been used in an attempt to reduce the incidence of haematoma and wound infection. Unfortunately, they tend to introduce organisms into an otherwise clean area and increase the incidence of wound infection (Cruise and Foord 1973). In addition, pelvic drains do not reduce infection following radical pelvic surgery (Orr et al 1987). Careful attention to haemostasis is preferable and drains should be avoided in most closures.

Closure of peritoneum

This practice has been questioned recently. Research in animal models has suggested that closure of the peritoneum increases rather than decreases peritoneal adhesions. Human studies support this finding, showing that closure of the pelvic peritoneum does not reduce the incidence of postoperative adhesions or obstruction (Table 8.1; Tulandi et al 1988). The peritoneum spreads rapidly across any raw areas left after surgery, although devascularized tissue, such as pedicles, are a focus for adhesion formation. Practice still varies with regard to peritoneal closure, although it probably results in increased adhesion formation (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists 1998). However, if a suction drain is used in the wound, the peritoneum must be closed to avoid drawing the bowel into the wound.

Table 8.1 The effect of peritoneal closure on wound infection and adhesion formation.

| Closed (%) | Not Closed (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Wound infection | 3.6 | 2.4 |

| Adhesions | 22.2 | 15.8 |

| Obstruction | 1.6 | 0 |

Source: From Tulandi T, Hum HS, Gelfand MM 1988 Closure of laparotomy incisions with or without peritoneal suturing and second look laparoscopy. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 158:536, with permission of Elsevier.

Ureteric Damage

The ureter at the pelvic brim and ovarian fossa

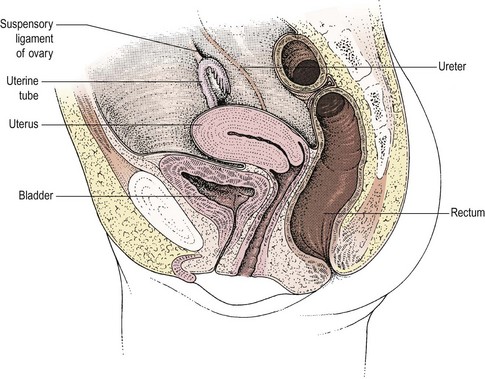

At the pelvic brim, the infundibulopelvic ligament with the ovarian vessels also crosses the iliac vascular bundle, usually 1–2 cm distal to the bifurcation of the common iliac artery and the ureter (Figure 8.3). At this point, the ureter and the ovarian vessels are running in parallel in a similar plane and may be confused if care is not taken. Occasionally, the ureter may be duplex. Where the ureter runs lateral to the ovary, it will almost inevitably be associated with any inflammatory or malignant mass. Happily, it will lie on the lateral aspect of the mass where it can be identified and dissected free, usually without difficulty, although in patients with endometriosis, the ureter may be fixed in dense fibrosis.

The lower ureter

The third position where the ureter is at risk is in the ureteric tunnel, where the ureter crosses beneath the uterine artery but superior to the cardinal ligament and approximately 1–1.5 cm lateral to the angle of the vagina (Figure 8.4

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree