Introduction

Amenorrhea is defined as the absence or the abnormal cessation of menses. The term primary amenorrhea refers to the failure to menstruate by age 15 in the presence of normal secondary sex characteristics or within 5 years after breast development if thelarche occurs before age 10. Other clinical situations which require investigation include failure to initiate breast development or absence of other secondary sex characteristics by age 13.

The causes of primary amenorrhea are numerous and may be physiologic, endocrine or anatomic. Pregnancy is an example of a physiologic cause of both primary and secondary amenorrhea. Endocrine causes include failed maturation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis or gonadal failure as seen in Turner’s syndrome. Gonadal failure accounts for over 40% of cases of primary amenorrhea. Anatomic causes include obstruction of the lower reproductive tract as in mullerian agenesis or Mayer Rokitansky Kuster Hauser syndrome (MRKH). This accounts for another 15% of primary amenorrhea. Another 10% of primary amenorrhea will be due to constitutional delay. Finally, in rare cases, polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) may present as primary amenorrhea, as metabolic syndrome and obesity are now epidemic in the adolescent population. PCOS is the subject of Chapter 93. This chapter will focus on the endocrine causes of primary amenorrhea.

In order to understand how primary amenorrhea is evaluated, it is necessary to understand the basic embryology of sex development, how the internal and external genitalia form and under what influences. Prior to 6–9 weeks of gestation, the fetus contains bipotential gonads, and both the mullerian and wolffian ducts. The SRY region on the Y-chromosome then acts on the bipotential gonad to differentiate into a testis instead of an ovary (the default). Once formed, the testes secrete two substances. The first is testosterone, which causes further growth of the wolffian ducts and testicular descent. Eventually the wolffian ducts become the seminal vesicles, the vas deferens, and the epididymis. Testosterone is converted into dihydrotestosterone which is responsible for male secondary sex characteristics such as changes in voice, penile growth, and pubic hair growth. The second substance secreted by the testis is mullerian inhibiting substance (MIS), which causes regression of the mullerian ducts.

In women, with the absence of the SRY gene, the germ cells in the bipotential gonad develop into the ovaries and there is no MIS to inhibit the growth of the mullerian ducts. Since there is nothing to support wolffian duct development, they regress. The mullerian ducts eventually become the fallopian tubes, uterus, and the upper third of the vagina. The lower two-thirds of the vagina is formed from the urogenital sinus. The estrogen secreted by the ovaries supports female secondary characterstics such as breast development at puberty.

Keeping this embryology in mind, when encountering a patient with primary amenorrhea, the history should focus around several key questions. Is there a history of abnormal or delayed growth as a child? This might suggest an endocrine cause at the level of the hypothalamus or pituitary. Any history of pelvic pain and is it cyclic? This would suggest lower genital tract outflow obstruction. Any history of breast discharge, headache or visual symptoms suggesting a prolactinoma? It is important to ask about activity and nutritional status since extremes of weight are associated with hypothalamic amenorrhea. Any history of childhood cancers, chemotherapy or pelvic radiation? These treatments are associated with gonadal failure from accelerated oocyte loss. Finally, it is important to take a complete history, focusing on present systemic illnesses, family history and reproductive history, as well as any medications that the patient is currently taking.

Physical exam should focus on the presence or absence of secondary sex characteristics. Breast development (Tanner staging) reflects estrogen status while pubic hair growth reflects androgen exposure. Bodyweight and height should be noted. A careful skin exam could reveal hirsutism, virilism, neurofibromas, café-au-lait spots, acne, acanthosis, myxedema, striae on the abdomen or male-pattern hair distribution. Head and neck exam should rule out the presence of exophthalmos, cleft lip or palate. Abdominal exam should include the presence or absence of palpable abdominal masses, and an inguinal exam. Finally, careful examination of the external genitalia should be performed since it will be abnormal in 15% of women with primary amenorrhea. Ultrasound should then be performed to look for the presence of a uterus.

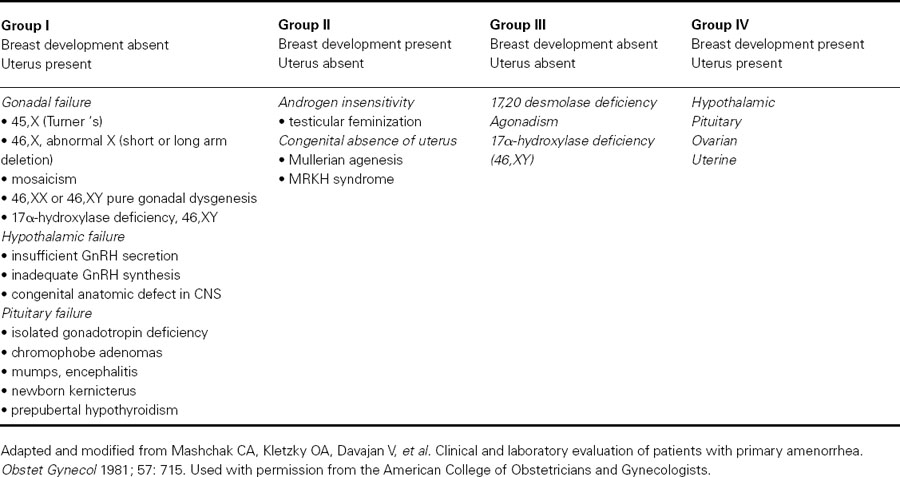

Based on the presence or absence of a uterus and breast development, there are four distinct phenotypes of individuals with primary amenorrhea (see Table 89.1).

- Group I: absent breast development but uterus present

- Group II: breast development present but uterus absent

- Group III: absence of both breast and uterus

- Group IV: presence of both breast development and uterus

Table 89.1 Classification of disorders with primary amenorrhea according to breast and uterine development

Individuals with primary amenorrhea who lack breast development but who have a uterus have a defect in estrogen action somewhere along the HPO axis, either at the level of the hypothalamus/pituitary (hypothalamic hypogonadism) or at the level of the ovary (hypergonadotropic hypogonadism). These two etiologies can be differentiated by measuring serum FSH and LH. Serum gonadotropin levels are low in hypothalamic/pituitary causes, while they are elevated in primary gonadal disorders.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree