Although obstetricians-gynecologists have focused on the management of abnormal gynecologic conditions, they also have a traditional role of providing primary and preventive care to women, particularly for women of reproductive age. The obstetrician-gynecologist often serves as a woman’s point of entry into the health care system, her primary care clinician, and a source of continuity of care (1). Primary care emphasizes health maintenance, preventive services, early detection of disease, and availability and continuity of care. The value of preventive services is apparent in such trends as the reduced mortality rate from cervical cancer that resulted, in large part, from the increased use of cervical cytology testing. Neonatal screening for phenylketonuria (PKU) and hypothyroidism are examples of effective mechanisms for prevention of mental retardation. Women often regard their gynecologist as their primary care provider; indeed, many women of reproductive age have no other physician. Obstetricians-gynecologists estimated that at least a third of their nonpregnant patients rely on them for primary care (2). As primary care physicians, obstetricians-gynecologists provide ongoing care for women through all stages of their lives—from reproductive age to postmenopause. In this role, some gynecologists include as a routine part of their practices screening for certain medical conditions, such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and thyroid disease, and management of those conditions in the absence of complications.

Some traditional aspects of gynecologic practice, such as family planning and preconception counseling, are recognized as effective preventive health measures, although clear and coherent national guidelines and goals for preventing unintended pregnancies have not been a high priority in the United States (3). Preventive medical services encompass screening and counseling for a broad range of health behaviors and risks, including sexual practices; prevention of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs); use of tobacco, alcohol, and other drugs; diet; and exercise.

The Institute of Medicine defined primary care as “the provision of integrated, accessible health care services by clinicians who are accountable for addressing a large majority of personal health care needs, developing a sustained partnership with patients, and practicing in the context of family and community” (4). Integrated care is further defined as being comprehensive, coordinated, and continuous. The definition states that primary care clinicians have the appropriate training to manage most problems that afflict patients (including physical, mental, emotional, and social concerns) and to involve other practitioners for further evaluation or treatment when appropriate. Using data from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Surveys, physician specialty groups were analyzed in a study to determine how well these Institute of Medicine primary care definitions applied to the care delivered by each specialty (5). In this analysis, obstetrics and gynecology as a specialty demonstrated some characteristics of primary care that applied to the traditional specialties of internal medicine, family and general physicians, and pediatrics. As a category, however, obstetrics and gynecology was more closely related to medical and surgical subspecialties (5). This analysis would be accepted by many practicing obstetricians and gynecologists who state that the specialty provides both primary and specialty care.

The Institute of Medicine definition includes referral, coordination, and follow-up care, but specifically does not include the function of “gatekeeper” as essential for a primary care clinician. As the US health care system has evolved, health maintenance organizations and insurers have responded to women’s resolute support of direct access to obstetricians-gynecologists, a concept also strongly supported by the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (6).

There is an increasing emphasis on women’s health and gender-specific medicine. Physicians have become more knowledgeable about the differences in pathophysiologic aspects of diseases in women compared with men and thus better equipped to manage them. One example is an increasing emphasis on women’s cardiovascular health with preventive care and screening for risk factors.

Gynecologist as Primary Care Provider

The obstetrician-gynecologist frequently serves as a primary medical resource for women and their families, providing information, guidance, and referrals when appropriate. Routine health care assessments for healthy women are based on age groups and risk factors. Health guidance takes into account the leading causes of morbidity and mortality within different age groups. Patient counseling and education require an ability to assess individual needs, to assess stages of readiness for change, and to use good communication skills, including motivational interviewing to encourage behavioral changes and ongoing care (7). A team approach to care is frequently helpful, utilizing the expertise of medical colleagues, such as nurses; advanced practice nurses, including nurse midwives and nurse practitioners; health educators; other allied health professionals, such as dieticians or physical therapists; relevant social services; and other physician specialists. All clinicians, regardless of the extent of their training, have limitations to their knowledge and skills and should seek consultation at appropriate times for the benefit of their patients in providing both reproductive and nonreproductive care.

The National Ambulatory Care Surveys from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention include obstetrician-gynecologists among primary care specialties as opposed to medical or surgical subspecialties (8). Women’s needs for primary care vary across their lifespan. One survey of women’s satisfaction with primary care found that women in their early reproductive years (ages 18–34) were more satisfied with care coordination and comprehensiveness when their regular provider was a reproductive health specialist, primarily an obstetrician-gynecologist physician as compared to a generalist, a generalist clinician plus an obstetrician-gynecologist, or no regular provider (9). The scope of services provided by obstetricians-gynecologists varies from one practice or clinician to another and may include more or fewer aspects of well-woman and reproductive health care. It is important to establish with each patient whether she has a primary care clinician and who will be providing primary care and preventive health services (1).

Guidelines for primary and preventive services are issued by a number of medical bodies including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American Academy of Family Physicians, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), and the American Medical Association (1,10–14). The guidelines from various organizations differ somewhat in their specific details, and a national guideline clearinghouse for evidence-based clinical practice guidelines, sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), is available to provide comparisons between guidelines for a given medical condition or intervention (15).

In 2006 in the United States, there were approximately 660 million visits by women to ambulatory medical care providers (16). In the past, approximately eighteen percent of the visits were made to gynecologists (17). Less than a third of ambulatory visits were made by individuals between the ages of 15 and 44 years, and this percentage is declining with an aging population (16). Normal pregnancy and gynecologic examination were among the most common reasons for care.

When asked to characterize the nature of an office or clinic visit, obstetricians-gynecologists may or may not identify themselves as primary care providers, depending on a number of variables (18). Those variables may include the patient’s age, pregnancy status, whether it is a new versus a return visit, the diagnosis, insurance or referral status, and even geographic practice region. Primary and preventive services clearly within the realm of obstetricians and gynecologists include cervical cytology testing, pelvic examination and breast examination, and family planning services including contraception. When compared with other physicians, obstetricians-gynecologists are more likely than other physicians to perform cervical cytology testing, pelvic examination, and breast examination.

Approaches to Preventive Care

In health care, the focus is shifting from disease to prevention. Efforts are under way to promote effective screening measures that can have a beneficial effect on public and individual health. Following is a brief description of programs developed by American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the USPSTF, and the American Medical Association to provide guidelines for preventive care.

Guidelines for Primary and Preventive Care

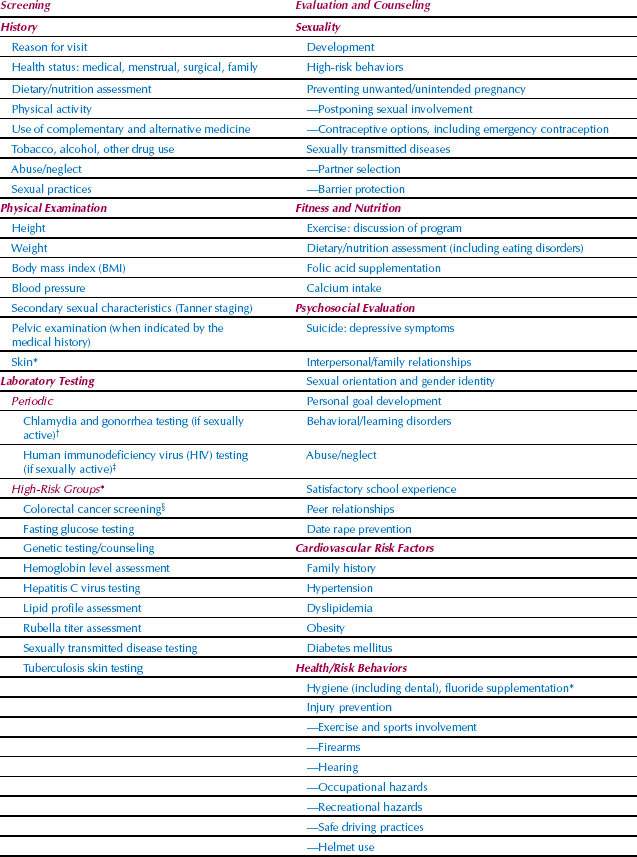

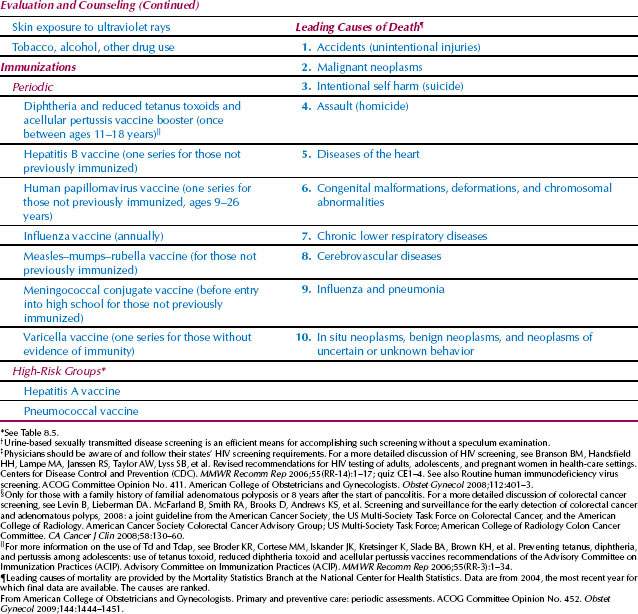

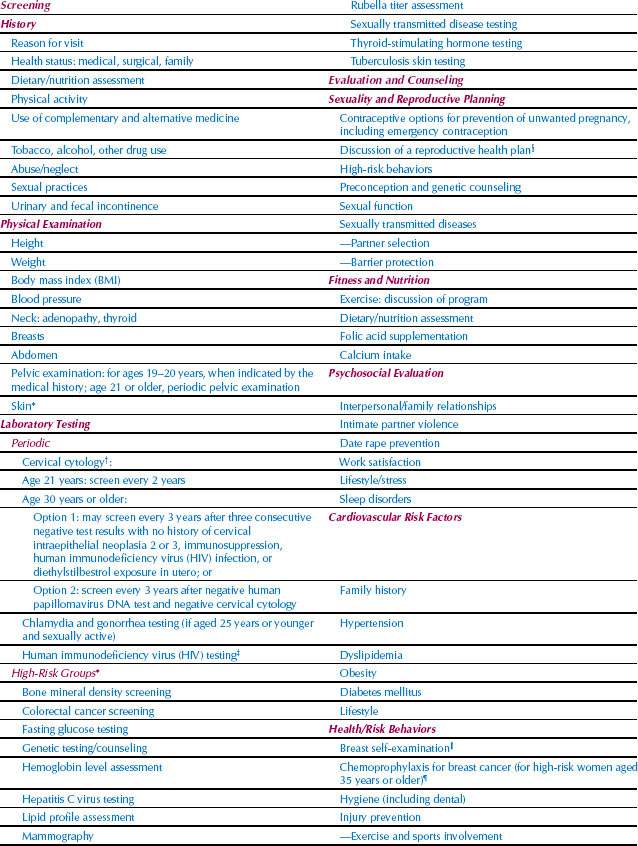

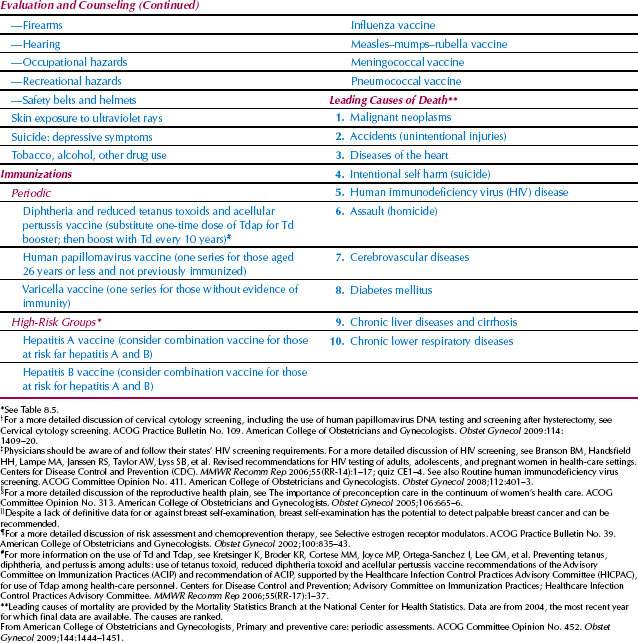

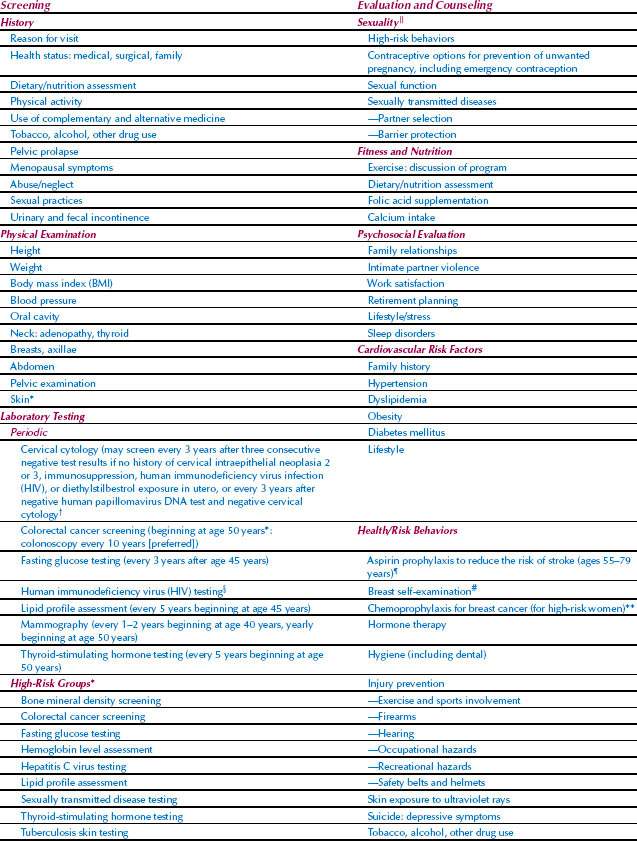

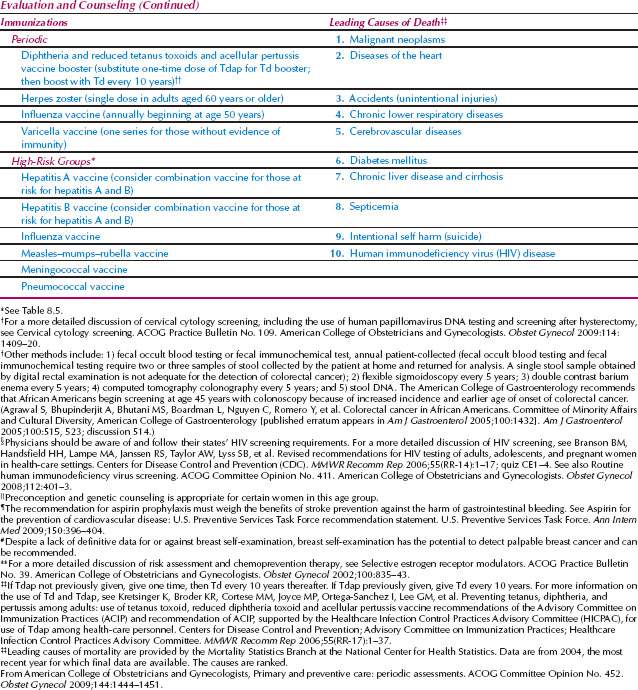

The initial evaluation of a patient involves a complete history, physical examination, routine and indicated laboratory studies, evaluation and counseling, appropriate immunizations, and relevant interventions. Risk factors should be identified and arrangements should be made for continuing care or referral, as needed. The ACOG recommendations for periodic evaluation, screening, and counseling by age groups, and the leading causes of death and morbidity within different age groups are shown in Tables 8.1 through 8.4 (10). These tables include recommendations for patients who have high-risk factors that require targeted screening or treatment; patients should be made aware of any high-risk conditions that require more specific screening or treatment (Table 8.5). Recommendations for immunizations, indicated according to age group, are available from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The CDC recommends HIV screening for pregnant women, adults, and adolescent patients in all health care settings after the patient is notified that testing will be performed, unless the patient declines (opt-out screening) (19). Subsequent care should follow a specific schedule, yearly or as appropriate, based on the patient’s needs and age.

Guide to Clinical Preventive Services

The USPSTF was commissioned in 1984 as a 20-member nongovernmental panel of experts in primary care medicine, epidemiology, and public health. The USPSTF, comprising primary care providers, now includes nonfederal experts in prevention and evidence-based medicine (such as internists, pediatricians, family physicians, gynecologists-obstetricians, nurses, and health behavior specialists); the task force conducts and publishes scientific evidence reviews on a variety of preventive health services with administrative and research support from the AHRQ. Initial and subsequent reviews and recommendations are being revised and periodically released on the Web site sponsored by the AHRQ (15). The charge to the panel was to develop recommendations for the appropriate use of preventive interventions based on a systematic review of evidence of clinical effectiveness. The panel was asked to rigorously evaluate clinical research to assess the merits of preventive measures, including screening tests, counseling, immunizations, and medications.

The task force uses systematic reviews of the evidence on specific topics in clinical prevention that serve as the scientific basis for recommendations. The task force reviews the evidence, estimates the magnitude of benefits and harms, reaches consensus about the net benefit of a given preventive service, and issues a recommendation that is assigned a grade from “A” (strongly recommends), to “B” (recommends), “C” (no recommendations for or against), “D” (recommends against), to “I” (insufficient evidence to recommend for or against) (Table 8.6). The grading system includes suggestions for practice, recommending that the service should be provided, discouraged, or that the uncertainty about the balance of benefits versus harms should be discussed. The levels of certainty regarding net benefit are ranked from high to moderate to low. The task force evaluates services based on age, gender, and risk factors for disease, making recommendations about which preventive services should be included in routine primary care for which populations. Primary preventive measures are those that involve intervention before the disease develops, for example, quitting smoking, increasing physical activity, eating a healthy diet, quitting alcohol and other drug use, using seat belts, and receiving immunizations. Secondary preventive measures are those used to identify and treat asymptomatic persons who have risk factors or preclinical disease but in whom the disease itself has not become clinically apparent. Examples of secondary preventive measures are well known in gynecology, such as screening mammography and cervical cytology testing.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>