Introduction

Surgical site infection is perhaps one of the most common complications associated with surgical management of patients and accounts for significant morbidity in 8–10% of gynecologic surgical hospitalizations. Despite vigorous preoperative vaginal cleansing, contamination by endogenous bacteria may occur at the time of gynecologic operations. There are many risk factors for surgical site infections. These include but are not limited to hemostatic sutures around crushed tissue, pooling of blood products in open defects, and bacterial contaminants from the vagina. These may all lead to pelvic cellulitis or pelvic abscesses and often require prolonged hospitalization, medical management with antimicrobials, and surgical debridement.

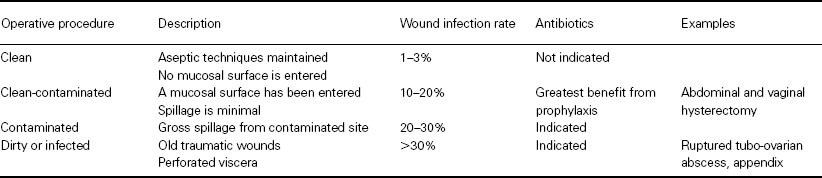

In general, all surgical procedures can be classified based on the type of procedure and the likelihood of subsequent infection (Table 54.1).

Table 54.1 Surgical wound classifications adopted by the American College of Surgeons

Aerobic and anaerobic bacteria are both represented in cultures from postoperative infections. Gram-positive cocci (streptococci and staphylococci) account for most of the organisms isolated. Escherichia coli and Bacteroides are the predominant gram-negative and anaerobic organisms, respectively.

Several measures may be employed in order to prevent and reduce the rates of infection following gynecology. These include: preoperative showering with an antiseptic soap, shaving of the incision site in the operating room, observation of sterile technique by all operating room personnel, adequate bowel preparation, and the use of prophylactic antibiotics as necessary.

The criteria for the use of prophylactic antibiotics in gynecology are as follows.

- The operation should involve a significant risk of postoperative site infection.

- The operation should cause bacterial contamination.

- The antibiotic should be targeted to the presumptive microbial contaminants.

- The antibiotic should be present in the target tissue at the time of the initial incision.

- The benefits of prophylactic antibiotics should outweigh the risks of use.

The use of prophylactic antibiotics has decreased operative site infection following vaginal hysterectomy from 32% to 6.3% [1], whereas for abdominal hysterectomies, infection rates with and without antibiotic prophylaxis have been reported to be approximately 9.0–9.8% and 21–23.4%, respectively [2,3].

A study by Burke showed that there was no benefit in using prophylactic antibiotics if they were administered more than 3 hours after bacterial contamination occurred [4]. Preoperative administration of an antimicrobial agent should precede any elective procedure requiring prophylaxis. A short-term course not to exceed 24 hours postoperatively should be employed unless the surgical procedure is prolonged beyond 3 hours or if there is blood loss in excess of 1500 mL. Additional antibiotic administration should be given in either of these events. Several agents have been used: ampicillin, doxycycline, metronidazole, and a variety of cephalosporins. Cephalothin, cephradine, cefazolin, cefoxitin, ceforanide, cefonicid, cefotetan, cefotaxime, ceftizoxime, and moxalactam provide broad-spectrum coverage and allow for a short period of administration. Metronidazole, considered to be effective only against obligate anerobes, is an acceptable prophylactic agent.

The initial dose of antibiotic is usually administered 30–60 minutes before the initial incision is made in order to attain satisfactory serum and tissue levels although administration (IV or IM) in the operating room following induction is acceptable and may be preferable if a short half-life antibiotic is used. Cefoxitin must be diluted with lidocaine prior to intramuscular injection to reduce pain at the injection site. A normal prothrombin time or 10 mg vitamin K administration is recommended prior to the use of drugs which are known to lead to hypoprothrombinemia and/or platelet dysfunction with or without clinical bleeding. Such drugs include cefamandole, moxalactam, and cefoperazone.

Other factors such as total operative time, estimated blood loss, regrowth of vaginal flora, and associated procedures performed at the time of hysterectomy have all been studied. Those patients who have the greatest amount of surgery performed (e.g. hysterectomy plus urogynecologic corrective procedures) are at highest risk of a postoperative infection. These infections usually occur more than 72 hours after surgery.

Patients with antibiotic allergies may reduce their risks of infection if their surgeon uses a closed T-tube suction drainage in the space between the peritoneum and vaginal cuff for the 36 hours immediately after surgery [5]. Also, a vaginal pack coated with sterile gel rather than antibiotic cream can reduce the amount of blood and blood products that accumulate between the peritoneum and vaginal cuff, thereby reducing a nidus for infection.

It is not advisable to alter the normal flora of the vagina prior to surgery. Preoperative vaginal douching with an iodophor solution the night before surgery has not been shown significantly to reduce the total number of organisms in the vagina. In fact, the number is reduced from 108 to 106–107

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree