Causes of congenital abnormalities, the majority being of unknown etiology.

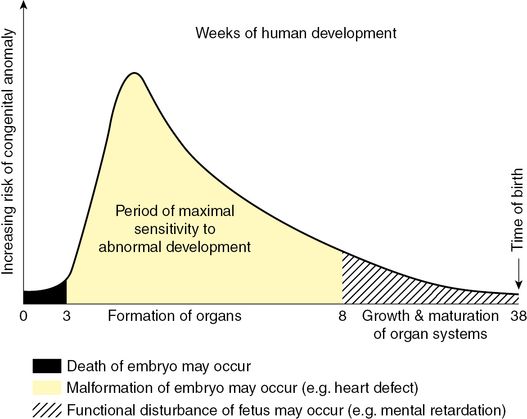

The susceptibility of an embryo or fetus for a teratogenic response is related to various factors, including the stage of development at the time of exposure, the amount of drug exposure, the chemical composition of the drug, the genetic make-up of the mother and other concurrent exposures. Exposure to a toxin during the pre-embryonic phase (up to 17 days postconception) when the cells are rapidly multiplying, either results in a miscarriage owing to death of the embryo or survival of a fetus without any harmful consequences: the ‘all or nothing’ effect[2]. Exposure to a drug during the embryonic phase from 18 days to 8 weeks postconception can result in permanent organ damage (teratogenicity). Beyond 8 weeks, if the fetus is exposed to drugs, it is unlikely to result in significant organ damage, although certain subtle changes in the growing organs, such as the brain, kidneys or gut, may go undetected until late in life. As the gestational age of exposure to a drug is the single most important determinant of the teratogenic potential, it becomes crucial to determine the correct gestational age of the fetus to be able to counsel about the potential risks involved (Figure 17.2)[1].

Schematic illustration showing the increasing risk of birth defects developed during organogenesis.

Counseling and management in pregnancy

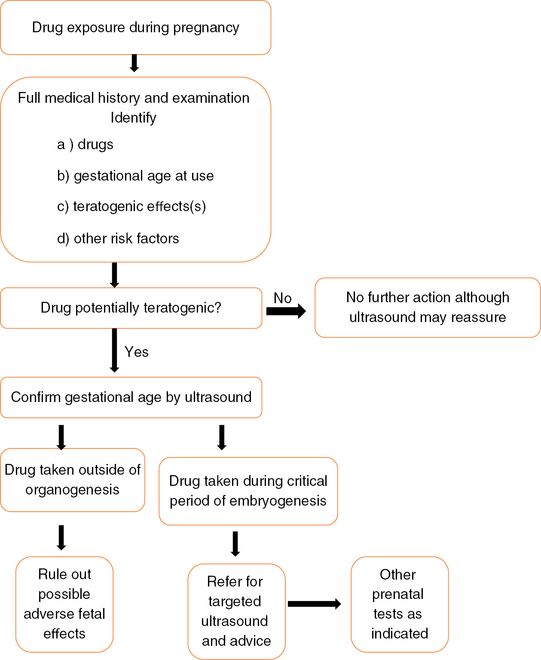

Good knowledge of basic embryology, as well as the physiologic changes encountered in pregnancy, is vital to aid appropriate counseling. As most women attend for an antenatal booking visit around 8–10 weeks of gestation, the majority of the vital organogenesis will have already occurred, and thus it is ideal for women to have preconception counseling about the potential benefits versus risks of medication. Clinical condition permitting, nonessential drugs should be discontinued and appropriate medication with the least teratogenic potential should be selected for treatment. Counseling for exposure to drugs or exogenous agents during pregnancy should be based on the principles discussed above, and patients should be made aware of the background risk of congenital anomalies to enable them to understand that even if a particular drug is considered to be safe based on animal or human studies, one can never guarantee that the fetus will not have any congenital abnormality. The flow diagram (Figure 17.3) below serves as a simplistic guide for counseling a drug-exposed pregnant woman[3].

Flow diagram for counseling a drug-exposed pregnant woman.

In cases where drugs are thought to be linked with congenital anomalies, a detailed ultrasound scan should be offered to check normality of the fetus. The woman must be informed beforehand of the limitations of scanning and that functional abnormalities, such as mental restriction, are not detectable on ultrasound scan.

In the UK, a clinician is immune from civil liability for the adverse effects on the fetus of a drug appropriately prescribed in pregnancy if it is in-line with established medical practice (Congenital Disabilities [Civil Liability] Act 1976). In situations where the clinician is confronted with having to offer advice to women who have inadvertently taken drugs for minor illnesses in pregnancy, it is best to base the advice on current information attained from the UK Teratology Information Service (UKTIS)[4].

Specific medications and pregnancy

Analgesics in pregnancy

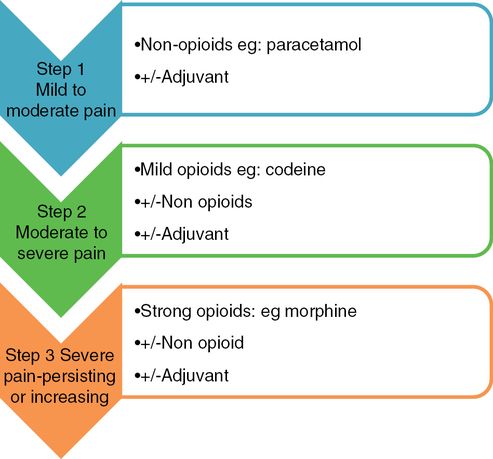

Analgesics are one of the most commonly used class of medications in pregnancy, either prescribed or bought over the counter. Although there are no clinical trials to recommend its applicability and safety, if used with caution, the World Health Organization analgesic ladder (Figure 17.4) may serve as a simplistic model for control of pain during first two trimesters of pregnancy[2].

The World Health Organization analgesic pain relief ladder.

In-utero exposure to paracetamol has not been known to be associated with an increased risk of congenital abnormalities. Paracetamol usage in therapeutic dosages or paracetamol poisoning in pregnancy per se is not an indication for termination of pregnancy or any additional fetal investigations[4].

Aspirin, a commonly used nonselective nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), has been shown to be teratogenic in animal studies when taken in high doses (>300 mg/day) and when consumed in analgesic doses, particularly in late gestation, may have adverse effects including increased risk of maternal and neonatal bleeding due to its antiplatelet effects, premature closure of ductus arteriosus (DA) in utero, and thus is best avoided, particularly in the third trimester. However, aspirin exposure at any stage of pregnancy is not in itself a ground for termination of pregnancy or for any further diagnostic tests. Low-dose aspirin, commonly used for its antiplatelet effect in pregnancy is not known to cause any adverse fetal or maternal effects.

NSAIDs should generally be avoided during the third trimester due to their association with an increased risk of premature closure of DA and oligohydramnios. It is advised that any NSAID exposure after 30 weeks of pregnancy should be monitored by fetal echocardiogram and serial scans for early detection of ologohydramnios. However, inadvertent exposure to NSAIDs at any stage in pregnancy is not an indication for termination of pregnancy in the absence of other indications. Ibuprofen is the preferred NSAID if clinically indicated in the first two trimesters of pregnancy[4].

Opioids are considered reasonably safe for use during pregnancy and are commonly prescribed for pain relief as second-line treatment. If used regularly in the third trimester close to delivery, one should ensure close monitoring of the newborn to detect opioid withdrawal symptoms.

Anticonvulsant drugs in pregnancy

Evidence suggests that congenital malformations linked with epilepsy are perhaps a combination of exposure of anticonvulsants in an individual who may be genetically susceptible. Polytherapy in contrast to monotherapy is known to increase the risk of anomalies. Kaneko et al. reported a 6.5% malformation rate with multiple drugs compared to 15.6% amongst women on a single drug[5]. The most common congenital malformations associated with the intake of antiepileptics, particularly first-generation drugs such as phenytoin and phenobarbitone, are neural tube defects (spina bifida and hydrocephalus), cardiac and skeletal malformations and cleft lip and palate. Fetal anticonvulsant syndrome, characterized by midfacial abnormalities such as wide-spaced eyes, depressed nasal bridge, low-set ears and hypoplasia of distal digits, has been associated with the use of these antiepileptic drugs. Second-generation drugs, such as sodium valproate and carbamazepine, have also been associated with neural tube defects, with a quoted risk of about 2% for spina bifida with valproate and 1% with carbamazepine[2]. A statistically significant association has been noted with cleft lip and/or palate and use of valproate and carbamazepine in pregnancy, the risk being more from valproate usage.

Lamotrigine, increasingly used for monotherapy, has been found to have a major malformation rate of 2.9% in the UK Registry, with a clear dose–response effect similar to valproate exposure[2]. The available published data on levetiracetam administration during pregnancy suggests an overall risk (2.2%) of major congenital malformations, which is well within the background risk (1–3%), the risk being lower (1.3%) with monotherapy compared to polytherapy (4%)[6]. There is no known effect on long-term developmental outcome, and further study results are awaited before labeling it as one of the safest antiepileptic in pregnancy.

Supplementation with high-dose folic acid (5 mg/day) is recommended for patients on anticonvulsants in the preconception period and throughout pregnancy.

Anticoagulants in pregnancy

Low molecular weight heparins (LMWH), such as enoxaparin, dalteparin and tinzaparin, are much more commonly used in pregnancy in UK and are overall known to be as efficacious and safe as unfractionated heparin. Danaparoid sodium is a LMWH with very little cross-reactivity with other heparins, and thus may be used as an alternative in pregnant women allergic to heparins or who develop heparin induced thrombocytopenia, an antibody-mediated reaction, which usually develops 5–10 days after initiation of heparin treatment. Any further treatment with heparin is contraindicated as there is a potential risk of life-threatening thrombus formation in this condition[7]. Heparins, however, do not cross the placenta due to their large molecular size, and thus there are no known risks to the fetus with their usage.

Warfarin is a coumarin anticoagulant that acts by blocking the activation of vitamin K-dependent clotting factors across the placenta and is a known teratogen. Studies looking at exposure to warfarin in first trimester of pregnancy have reported a risk as high as 30% of warfarin embryopathy or fetal warfarin syndrome (FWS), whilst more recent reports suggest a risk of 6–10%. FWS is characterized by nasal hypoplasia, stippled chondral calcification (chondrodysplasiapunctata) and scoliosis and fetal bleeding complications. This risk may be dose-dependent with doses higher than 5 mg/day carrying a higher risk. Exposure in later gestations may still be associated with central nervous system (CNS) and eye anomalies[4]. Warfarin exposure should be avoided in pregnancy and the anticoagulant should be changed to a LMWH prepregnancy or as soon as pregnancy is suspected.

The only exceptions are women with prosthetic heart valves in whom thromboembolic prophylaxis may need to be achieved with warfarin even in early pregnancy. Use of LMWH is not considered adequate in this situation[8]. While inadvertent warfarin exposure would not be regarded as medical grounds for termination of pregnancy, detailed ultrasound scans to screen the exposed fetus for any major structural malformations should be requested from the fetal medicine department[4].

Antiasthmatics in pregnancy

Treatment of asthma during pregnancy is no different from that in nonpregnant woman and the majority of the antiasthmatic drugs are considered safe during pregnancy. There is conflicting evidence about the safety of systemic steroids such as prednisolone in the first trimester as these may be associated with an increased risk of oral clefts[9]. Topical and inhaled or nebulized exposure is not known to carry any increased risks. It is, however, recommended that steroids in any form – inhaled, nebulized, oral or parenteral – should not be withheld in pregnancy as inadequate treatment is likely to lead to exacerbation of asthma, putting the mother and fetus both at increased risks. Maternal folate supplementation during early pregnancy may reduce the risk of oral clefts according to some studies[4].

Beta-agonists, such as salbutamol and terbutaline, are also considered safe in pregnancy and no adverse fetal or neonatal effects have been reported with their usage in pregnancy.

Antibiotics in pregnancy

It is advisable to treat pregnant women with the standard adult doses of antibiotics whenever clinically indicated as inadequate treatment is more likely to cause maternal and fetal harm by its inability to control infectious illness during pregnancy (Table 17.1). Penicillins or cephalosporins may be commenced when urgent treatment is indicated for maternal infections while awaiting results of culture and sensitivity. In cases of preterm premature rupture of membranes, the prophylactic antibiotic of choice is erythromycin, while co-amoxiclav is best avoided due to increased risk of necrotizing enterocolitis[10]. A single dose of intravenous antibiotic in the form of cefuroxime with or without metronidazole is recommended as prophylaxis during cesarean sections and should be administered early enough for the antibiotic to be present in the blood circulation at the time of surgical incision[11]. This has not demonstrated any harmful effects on the baby.

| Antibiotic | Effects in pregnancy |

|---|---|

| Penicillins: amoxicillin, ampicillin, benzylpenicillin, co-amoxiclav, flucloxacillin | No evidence of any increase in risk of congenital anomalies with therapeutic doses. |

| Cephalosporins: cephalexin, cefaclor, cefadroxil, cefixime, cefuroxime, ceftriaxone | Majority of studies do not suggest increased risk of congenital malformations. Two small studies found an increases risk of cardiovascular defects and oral clefts but causal link with cephalosporins is unproven. |

| Tetracyclines: tetracycline, doxycycline, minocycline, oxytetracycline | Discoloration of teeth and bones as well as impaired bone growth is observed following second- or third-trimester exposure. Hence, should be generally avoided after the first trimester. |

| Aminoglycosides: gentamicin, neomycin | Based on limited data, there is no increased teratogenic risk, but theoretical concerns about fetal ototoxicity and nephrotoxicity exist. |

| Macrolides: erythromycin, clarithromycin, azithromycin | No established causal link with congenital anomalies. |

| Quinolones: ciprofloxacin, nalidixic acid, norfloxacin, ofloxacin | Based on limited data and theoretical risk of arthropathy, these are not generally recommended except for life-threatening conditions not responding to other antibiotics. If indicated, ciprofloxacin is the preferred agent. |

| Chloramphenicol | Based on limited data there is no increased risk. Near-term use may be associated with Grey baby syndrome, although supporting evidence for this is lacking. |

| Triemethoprim | Increased risk of neural tube defects, or-facial clefts and cardiac defects have been reported[4]. Theoretical concerns about folic acid deficiency also exist. |

| Nitrofurantoin | Not associated with increase in congenital malformations based on limited studies. Associated with hemolysis in patients with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency. |

| Metronidazole | Available data do not show any increase in risk of congenital malformations. |

Anti-HIV medications in pregnancy

Highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) usage in pregnancy has been reported to be associated with increased risk of gestational diabetes and preterm delivery. There are case reports of increased risk of congenital malformations following in-utero exposure to didanosine and efavirez. However, no other antiretrovirals have been known to be teratogenic[12].

Antiemetics in pregnancy

If nausea and vomiting in pregnancy are not controlled with conservative measures, drug treatment may be required. There is no evidence of teratogenesis with the use of commonly used antiemetics such as antihistamines, phenothiazines and pyridoxine[13,14] Dopamine antagonists like metoclopramide[15] and 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT3) antagonists such as ondansetron, although considered safe[16] and effective, are recommended as second-line therapy due to limited data.

Antihypertensive drugs during pregnancy

Labetolol, a combined alpha-beta adrenergic blocker, is offered as first-line treatment for hypertension in pregnancy[17]. Labetolol crosses the placenta and maternal serum and amniotic fluid levels are approximately similar nearly 1–3 h after a single intravenous dose[18]. Labetolol usage is not known to alter uteroplacental blood flow despite a reduction in maternal blood pressure, and although there are occasional observations of neonatal bradycardia and hypotension following treatment with labetolol of maternal hypertension near delivery, overall there is no evidence of clinically significant beta-blocker effect in mature infants. While there is limited evidence to prove its safety in the first trimester, there are no published reports of fetal malformations attributable to labetolol specifically in the available literature. Although fetal growth restriction is a potential side effect of all beta-blockers, benefits of controlling maternal hypertension with labetolol outweighs any potential small risks.

Methyldopa, a centrally acting antiadrenergic medication, has been the most frequently used medication for treatment of hypertension in pregnancy. Methyldopa crosses the placenta to achieve fetal concentrations similar to maternal serum levels, but there is no evidence of any risks to the fetus known with its usage in pregnancy.

Nifedipine, a calcium-channel blocker, is used for treatment of hypertension and increasingly for tocolysis in pregnancy. No increase in the risk of major congenital malformations is reported with its usage.

Exposure to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-I) and angiotensin–ll receptor blockers in the first trimester of pregnancy has been associated with an increased risk of congenital abnormalities, including cardiovascular, renal and CNS malformations, and therefore it is advisable to substitute these with an alternative antihypertensive treatment for managing hypertension prepregnancy[4]. ACE-I fetopathy, characterized by oligohydramnios, renal tubular dysgenesis, lung hypoplasia, persistent ductus arteriosus, mild-to-moderate growth restriction and fetal/neonatal death, has been observed following exposure to ACE-I in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy[4]. Exposure to ACE-I in pregnancy should be considered an indication for a detailed structural anomaly fetal scan, and careful monitoring of the pregnancy with advice from maternal and/or fetal medicine specialist, as well as UKTIS, is recommended[4].

There may be an increased risk of congenital abnormality and neonatal complications if thiazide diuretics are taken during pregnancy. Hence, alternative antihypertensive treatment should be considered for women in the reproductive age group on these medications if contemplating pregnancy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree