CHAPTER 7 Preoperative care

Choosing the Operation

Choosing the optimum surgical procedure is a crucial first step in the preoperative care of patients. All management options should be carefully considered after full and thorough assessment of the patient’s gynaecological as well as other coexisting medical conditions. All treatment options should be explored including no treatment, non-surgical alternatives or more conservative surgery. For example, a patient requesting sterilization should be informed about reversible long-term contraception, and she and her partner should be informed about vasectomy. Likewise, a patient requesting hysterectomy for menorrhagia should be informed of the reversible progestogen-releasing intrauterine system or less invasive endometrial ablation. It is the clinician’s duty to make the patient fully aware of all her options. All the pros and cons and implications of various treatments as well as no treatment should be fully explained to patients. The final decision on the optimum treatment should be mutually agreed between the surgeon and the patient, taking into consideration her wishes and social circumstances (General Medical Council 2008). Quite often, patients do not remember all the information given to them verbally during their consultation. It is therefore important to hand them printed leaflets containing more detailed information on their intended procedure, as well as other relevant treatments. These should also be available in languages other than English depending on the local demographics. With the availability of information on the Internet, patients are very likely to read up on their intended procedures from various unknown Internet sources. Clinicians should therefore direct their patients towards trusted websites offering unbiased information, such as that of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists which provides specific information leaflets for patients.

Consent

Valid consent

It is a legal requirement and an ethical principle to obtain valid consent before starting any treatment or investigation. Although verbal consent is acceptable for most investigations and medical treatments, it is necessary to obtain written and signed consent before any surgical intervention under anaesthesia, with the exception of some emergency situations. For consent to be valid, it must be given voluntarily by an appropriately informed person (either the patient or someone with parental responsibility if the patient is under 16 years of age) who has the capacity to consent to the intervention. The woman must be informed regarding the nature of her condition. Written information should be given, especially as patients are often admitted on the day of surgery and have less time to ask questions. As discussed above, the patient must also be aware of the alternatives to surgery and the option of no treatment. The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, the General Medical Council and the Department of Health all place importance and have provided guidance on valid consent (Department of Health 2001, General Medical Council 2008, Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists 2008a).

Consent and operative risks

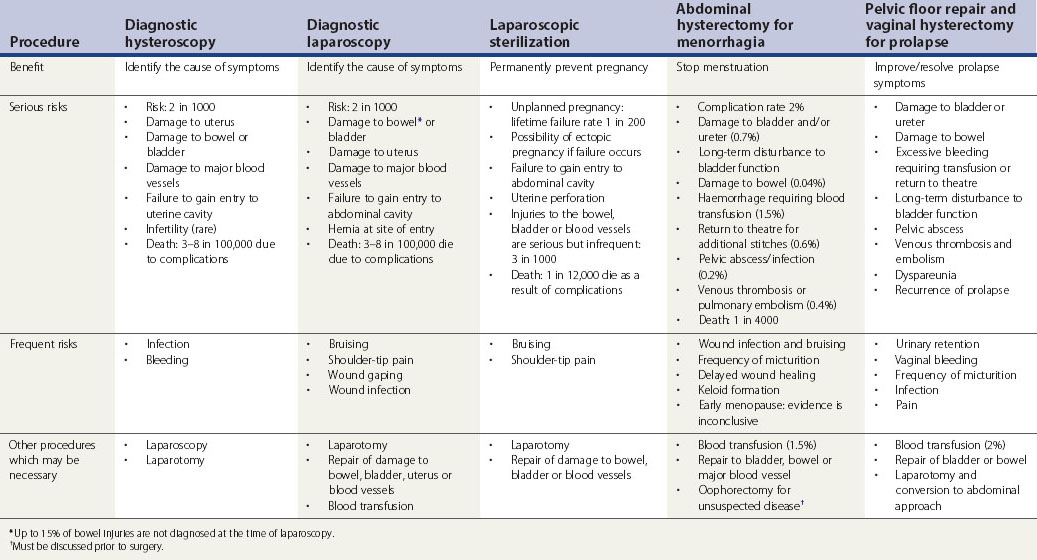

Patients should be informed of frequent and established serious adverse outcomes related to the procedure. The likelihood of complications associated with the intended surgical procedure should be presented in a fashion comprehensible to the patient. The discussion should include all possible intraoperative risks as well as short- and long-term postoperative complications. Table 7.1 summarizes the risks associated with common gynaecological operations as detailed by the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (2004a–c, 2008a–d).

Consent for additional procedures

It is always good practice to discuss, and include in the consent, any possible additional procedures that may be required during the intended operation. Generally, any additional surgical treatment which has not previously been discussed with the woman should not be performed, even if this means a second operation (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists 2008a). One must not exceed the scope of authority given by the woman, except in a life-threatening emergency. There are three different situations where an additional procedure may be necessary during the course of an elective surgery. Firstly, when a minor pathology related to the patient’s symptoms is detected such as endometriosis or adhesions in women undergoing laparoscopy for pelvic pain or infertility. In this situation, treatment can be performed if the patient has been made aware of this possibility and has consented for additional minor treatment. The second situation arises when a more complex disease is detected such as a pelvic mass, suspicious looking ovary, severe endometriosis or severe adhesions. Surgery in these situations should be deferred to a second operation after adequate counselling of the patient. In particular, oophorectomy for unexpected disease detected at surgery should not normally be performed without previous consent. The third situation involves intraoperative complications such as injury to the bowel or urinary tract that could lead to serious consequences if left untreated. Corrective surgery must proceed in these cases, and full explanation should be given as soon as practical following surgery.

Who should obtain the consent?

It is the responsibility of the clinician undertaking the surgical procedure to obtain consent. However, if this is not possible, it may be delegated to another doctor who is adequately trained and has sufficient knowledge of the procedure to be performed (General Medical Council 2008). The consent, however, remains the responsibility of the surgeon performing the operation. The clinician obtaining the consent should see the patient on her own first, for at least part of the consultation. She should then be allowed the company of a trusted friend or relative for support if she wishes. If consent is taken on the day of surgery, enough time should be allowed for discussion (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists 2008a).

Additional consents

Duration of consent

The consent will remain valid indefinitely unless withdrawn. However, if new information is available between the consent and the procedure (e.g. new evidence of risk or new treatment options), the doctor should inform the patient and reconfirm the consent. It is also wise to refresh the consent form if there is a significant amount of time between consent and the intervention (Department of Health 2001).

Consent of special groups of patients

Jehovah’s Witnesses

Jehovah’s Witnesses are an Adventist sect of Christianity founded in the USA in the late 19th Century. They believe that accepting a blood transfusion, even autologous blood transfusions in which one’s own blood is stored for later transfusion, is a sin. This includes red blood cells, white blood cells, platelets and plasma. Jehovah’s Witnesses are aware of the possible risk to life in refusing blood transfusion and they take full responsibility for this. It is important to respect their wishes and to consider alternative measures to blood transfusion. There are special consent forms for Jehovah’s Witnesses’ refusal of blood products, stating clearly that this may result in the death of the patient. They also specify what blood fractions they might accept (e.g. interferons, interleukins, albumin, clotting factors or erythropoietin) as well as any blood salvage procedures, such as cell saver that recycles and cleans blood from a patient and redirects it to the patient’s body. More information can be found on the official website of Jehovah’s Witnesses (www.watchtower.org).

Adults without capacity

The Mental Capacity Act 2005

Certain procedures such as sterilization, management of menorrhagia and abortion do occasionally arise in women with severe learning disabilities who lack capacity to consent. They give special concern about the best interests and human rights of the person who lacks capacity. They can be referred to court if there is any doubt that the procedure is the most appropriate therapeutic recourse. The least invasive and reversible option should always be favoured (Department of Health 2001).

Children and young people

Finally, refusal of treatment by a competent child and persons with parental responsibility for a child can be over-ruled by a court if this is in the best interests of the child (Department of Health 2001).

Preoperative Assessment

Risk assessment

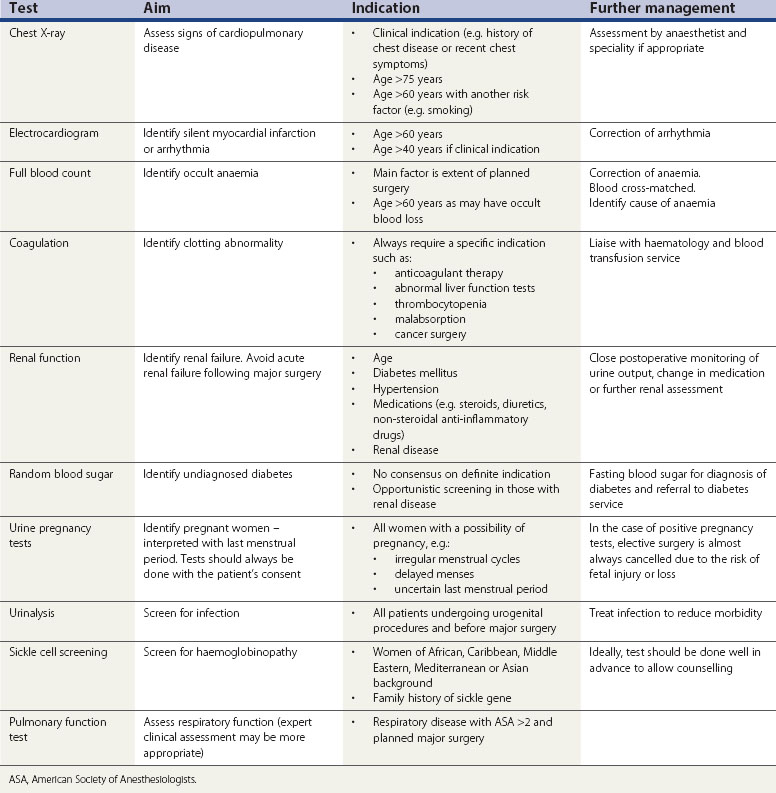

One should start with a thorough assessment of the patient’s risk by way of a full medical and surgical history followed by general examination. This will determine which patients require further investigations. Routine preoperative testing of healthy individuals is of little benefit. Guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2003) conclude that no routine laboratory testing or screening is necessary for preoperative evaluation unless there is a relevant clinical indication. Preoperative testing is a substantial drain on NHS resources, and substantial savings can be achieved by eliminating unnecessary investigations (Munro et al 1997). False-positive results may also cause unnecessary anxiety and result in additional investigations causing a delay in surgery. The indications and aims of common preoperative tests are shown in Table 7.2.