CHAPTER 14 Pregnancy: Second Trimester

HEARTBURN (GASTROESOPHAGEAL REFLUX) IN PREGNANCY

Heartburn is caused by a reflux of gastric acids into the lower esophagus, usually occurring after meals or when lying down.1 The gastric acids irritate the esophagus, causing a burning sensation behind the sternum that may extend into the neck and face, and may be accompanied by regurgitation, nausea, and hypersalivation. Inflammation and ulceration of the esophagus may result.2 Up to two-thirds of women experience heartburn during pregnancy.3 Only rarely it is an exacerbation of pre-existing disease. Symptoms may begin as early as the first trimester and cease soon after birth. Most women first experience reflux symptoms after 5 months of gestation; however, many women report the onset of symptoms only when they become very bothersome, long after the symptoms actually began.3 The prevalence and severity of heartburn progressively increases during pregnancy.4

The exact causes(s) of reflux during pregnancy include relaxed lower esophageal tone, secondary to hormonal changes during pregnancy, particularly the influence of progesterone, and mechanical pressure of the growing uterus on the stomach which contributes to reflux of gastric acids into the esophagus.3 However, some studies have demonstrated that, in spite of increased intra-abdominal pressure as the uterus expands as pregnancy progresses, the high abdominal pressure and the low pressure in the esophagus are maintained by a compensatory increase in lower esophageal sphincter (LES) pressure, supporting the finding by Lind et al. that the LES pressure rose in response to abdominal compression in pregnant women without heartburn.3 Other possible contributing factors include an alteration in gastrointestinal transit time. For example, some studies have suggested that ineffective esophageal motility (decreased amplitude of distal esophageal contractions) is the most common motility abnormality in GERD.5

CONVENTIONAL TREATMENT APPROACHES

Medical treatment in pregnancy focuses on symptomatic relief. Complications due to reflux in pregnancy are rare because of its short duration, and thus upper endoscopy and other diagnostic tests are not typically indicated.3 Complications, however, can include esophagitis, bleeding, and stricture formation. Care should follow a “step-up algorithm” (start with simple and noninterventional strategies and add on as needed) beginning with lifestyle modifications and dietary changes. Antacids or sucralfate are considered the first-line drug therapies. If symptoms persist, histamine-2-receptor (H2) antagonists can be used. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are reserved for women with intractable symptoms or complicated reflux disease. Promotility agents may also be used. All but omeprazole are FDA category B drugs during pregnancy. Most drugs are excreted in breast milk. Of systemic agents, only the H2 receptor antagonists, with the exception of nizatidine, are safe to use during lactation.3

There are limited data regarding the safety of antacids during pregnancy, and teratogenicity is a significant concern.3 One retrospective case controlled study in the 1960s reported a significant increase in major and minor congenital abnormalities in infants exposed to antacids during the first trimester of pregnancy.3 Analysis of individual antacids has shown no such associations, and most aluminum-, magnesium-, and calcium-containing antacids are considered acceptable in normal therapeutic doses during pregnancy.3 One study “found a higher rate of congenital anomalies in children of women who took an antacid in the first trimester.”6 Side effects of antacids are diarrhea, constipation, headaches, and nausea. Compounds containing magnesium trisilicate can lead to fetal nephrolithiasis, hypotonia, respiratory distress, and cardiovascular impairment if used long-term and in high doses. Magnesium sulfate can slow or arrest labor and may cause convulsions. Magnesium-containing antacids should be avoided during the last few weeks of pregnancy. Antacids containing sodium bicarbonate should not be used during pregnancy because they can cause maternal or fetal metabolic alkalosis and fluid overload. Pregnant women receiving iron for iron deficiency anemia should be monitored carefully when antacids are used, because normal gastric acid secretions facilitate the absorption of iron, and iron and antacids should be taken at different times during the day to avoid problems.3 There are also little data to support the efficacy of antacids during pregnancy.6

Medications for treating GERD are not routinely or rigorously tested in randomized, controlled trials in pregnant women because of ethical and medicolegal concerns. Most recommendations arise from case reports and cohort studies by physicians, pharmaceutical companies, or the FDA. Voluntary reporting by the manufacturers suffers from an unknown duration of follow up, absence of appropriate controls, and possible reporting bias.3

Some believe that over-the-counter antacids should be avoided in pregnancy because they can lead to an excess intake of aluminum and salt and interfere with absorption of potassium, phosphorus, and calcium and drugs such as anticoagulants, salicylates, and vitamin E.7 One small double-blind randomized control trial in pregnancy was identified for H2-blockers. It found that 150 mg of Ranitidine taken twice daily improved symptoms over a placebo by 44% and supposedly demonstrated no risk. However, it mirrored the antacid alone group, which also had reduced symptoms of 44%.8

BOTANICAL TREATMENT

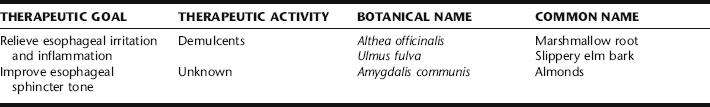

Herbal treatment for heartburn during pregnancy focuses on simple lifestyle and dietary modification, and the use of gentle herbs to soothe and protect the esophageal epithelium (Table 14-1). A mild antacid herb may also be included in more bothersome cases. Nervines (e.g., chamomile, skullcap, or passion flower) can be added to a protocol if heartburn is causing sleeping problems or if stress is contributing to digestive difficulties. Herbs for treating heartburn are best taken as teas or lozenges (e.g., slippery elm bark lozenges) rather than as tinctures, both to bathe the alimentary canal as they are ingested, and avoid the potentially irritating effects of alcohol in the tinctures. Further, demulcent herbs are best extracted in water for maximum efficacy (see Chapter 3).

General Recommendations for Preventing/Relieving Heartburn

Other practices may help to improve symptoms:

Interestingly, almost no clinical trials have been conducted demonstrating beneficial effects of eliminating offending foods or practices, including those listed in the preceding, with the exception of elevation of the head of the bed.12 Nonetheless, many women report improvement with a combination of these changes.

Discussion of Botanicals

Almonds

Chewing raw almonds is a treatment relied on by many midwives for the reduction of heartburn. Instruct clients to thoroughly chew 8 to 10 raw almonds and swallow. This may be repeated several times daily. Almonds are nutritive and there are no expected side effects or contraindications to the use of this food.

Marshmallow Root

Marshmallow root has similar properties to slippery elm—it is mucilaginous, soothing, and anti-inflammatory to epithelial surfaces. Evidence for the use of this herb stems largely from traditional use. Though this herb has been used for centuries, there are remarkably few clinical trials evaluating its safety or efficacy. It has no known expected toxic effects; however, it has been shown to lower blood sugar in animal studies. Caution should be observed when using this herb in combination with blood sugar lowering medications, though the risk is theoretical. It has been suggested theoretically that this herb might interfere with drug absorption. Although this has never been demonstrated clinically, it may be prudent to avoid taking this herb at the same time as taking other medicinal agents, and instead take marshmallow root and other medications several hours apart.13 Herbalists, however, commonly combine marshmallow with other herbs for the digestive tract. Unlike slippery elm, marshmallow is not available in convenient lozenges; therefore, it must be prepared as an infusion, and sipped as needed throughout the day or during an acute episode of heartburn.

Slippery Elm

Ulmus rubra is a nutritive demulcent, rich in mucilaginous polysaccharides. Slippery elm’s emollient actions have led to its traditional use for centuries for soothing irritated tissue, coating, and protecting the digestive tract.13 Its high calcium content may have some antacid effects. The herb may be taken as a tea; however, it has a thick, mucus-like consistency that can be unpleasant to women with NVP. To avoid this, one to two teaspoons of slippery elm can be added to oatmeal instead; it is has a pleasant, slight maple syrup–like flavor and is easy to take this way. The easiest and most effective way to use the herb is in the form of slippery elm lozenges, which may be purchased in a conveniently prepared form (e.g., Thayer Slippery Elm Lozenges), are quite palatable, and may sucked on as needed up to 8 to 12 per day. Supporting evidence for the herb’s benefits is drawn from traditional use, and extrapolation from effects of the mucilaginous constituent of the herb. There is no known toxicity, and in fact slippery elm has been used in some baby foods and adult nutritional foods.13

IRON DEFICIENCY ANEMIA

Iron is essential to multiple metabolic processes, including oxygen transport (e.g., critical to muscle and brain functioning), DNA synthesis, and electron transport. Iron balance in the body is carefully regulated to guarantee that sufficient iron is absorbed in order to compensate for body losses of iron. Either inadequate intake of absorbable dietary iron or excessive loss of iron from the body can cause iron deficiency. Menstrual losses are highly variable, ranging from 10 to 250 mL (4 to 100 mg of iron) per menses. Women require twice the iron intake of men to maintain normal stores, and can expect to lose approximately 500 mg of iron with each pregnancy without careful attention to adequate dietary intake and supplementation.14 Iron deficiency anemia occurs when all of the body’s iron stores have been entirely depleted. This chapter focuses on the iron needs of the pregnant and lactating woman.

Iron deficiency is the most common nutritional deficiency worldwide, affecting 20% of the world’s population. It is considered the most common health problem faced by women worldwide, adjusted for all ages and economic groups.15 Poor socioeconomic status does, however, further increase the risk of iron deficiency anemia.16 It is estimated that worldwide, 20% to 50% of all maternal deaths are related to iron deficiency anemia.17

During pregnancy the blood volume expands by about 35% to 50%, with additional iron required to meet the needs of the fetus, placenta, and increased maternal tissue. In the second and third trimesters, iron requirements increase to three times the nonpregnant needs. Women who do not supplement iron during pregnancy are usually unable to maintain adequate iron stores throughout and are at increased risk for developing iron deficiency anemia. Women who have a history of iron deficiency anemia prior to pregnancy, low iron stores at the onset of pregnancy, or those with heavy menstrual blood loss, are at further risk for anemia during pregnancy.14,18 Iron deficiency anemia decreases quality of life to due to symptoms of fatigue, weakness, loss of appetite, and increased susceptibility to infection (see Symptoms), and increases the risk of a number of problems including severe anemia from normal blood loss during labor requiring blood transfusions. Fetal iron stores in the first 6 months of life are dependent upon maternal stores during pregnancy.18 Postpartum anemia is a contributing factor to postpartum depression.18

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree