Few randomized trials evaluate preconceptional counseling efficacy, in part because withholding such counseling would be unethical. Also, because pregnancy outcomes are dependent on the interaction of various maternal, fetal, and environmental factors, it is often difficult to ascribe salutary outcomes to a specific intervention (Moos, 2004). There are, however, prospective observational and case-control studies that demonstrate the successes of preconceptional counseling. Moos and coworkers (1996) assessed the effectiveness of a preconceptional counseling program administered during routine health care provision to reduce unintended pregnancies. The 456 counseled women had a 50-percent greater likelihood of subsequent pregnancies that they considered “intended” compared with 309 uncounseled women. Moreover, the counseled group had a 65-percent higher rate of intended pregnancy compared with women who had no health care before pregnancy. There are interesting ethical aspects of paternal lifestyle modification reviewed by van der Zee and associates (2013).

COUNSELING SESSION

Gynecologists, internists, family practitioners, and pediatricians have the best opportunity to provide preventive counseling during periodic health maintenance examinations. The occasion of a negative pregnancy test is also an excellent time for education. Jack and colleagues (1995) administered a comprehensive preconceptional risk survey to 136 such women, and almost 95 percent reported at least one problem that could affect a future pregnancy. These included medical or reproductive problems—52 percent, family history of genetic disease—50 percent, increased risk of human immunodeficiency virus infection—30 percent, increased risk of hepatitis B and illegal substance abuse—25 percent, alcohol use—17 percent, and nutritional risks—54 percent. Counselors should be knowledgeable regarding relevant medical diseases, prior surgery, reproductive disorders, or genetic conditions and must be able to interpret data and recommendations provided by other specialists. If the practitioner is uncomfortable providing guidance, the woman or couple should be referred to an appropriate counselor.

Women presenting specifically for preconceptional evaluation should be advised that information collection may be time consuming depending on the number and complexity of factors that require assessment. The intake evaluation includes a thorough review of the medical, obstetrical, social, and family histories. Useful information is more likely to be obtained by asking specific questions regarding each history and each family member than by asking general, open-ended questions. Some important information can be obtained by questionnaires that address these topics. Answers are reviewed with the couple to ensure appropriate follow-up, including obtaining relevant medical records.

MEDICAL HISTORY

With specific medical conditions, general points include how pregnancy will affect maternal health and how a high-risk condition might affect the fetus. Afterward, advice for improving outcome is provided. Detailed preconceptional information regarding a few conditions is found in the next sections as well as in the other topic-specific chapters of this text.

Diabetes Mellitus

Diabetes Mellitus

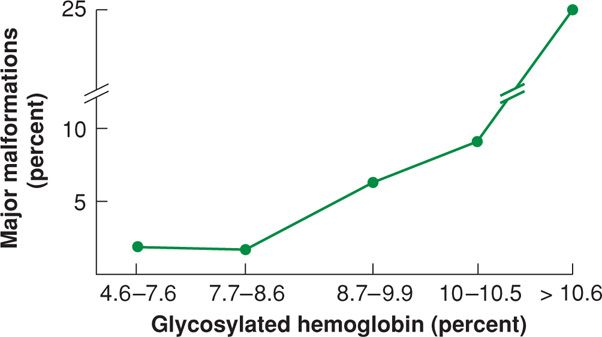

Because maternal and fetal pathology associated with hyperglycemia is well known, diabetes is the prototype of a condition for which preconceptional counseling is beneficial. Diabetes-associated risks to both mother and fetus are discussed in detail in Chapter 57 (p. 1125). Many of these complications can be avoided if glucose control is optimized before conception. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2012b) has concluded that preconceptional counseling for women with pregestational diabetes is both beneficial and cost-effective and should be encouraged. The American Diabetes Association has promulgated consensus recommendations for preconceptional care for diabetic women (Kitzmiller, 2008). These guidelines advise that a thorough inventory of disease duration and related complications be obtained and clinical and laboratory examination for end-organ damage be completed. Perhaps most importantly, they encourage a preconceptional goal of the lowest hemoglobin A1c level possible without undue hypoglycemic risk to the mother. In addition to assessing diabetic control during the preceding 6 weeks, hemoglobin A1c measurement can also be used to compute risks for major anomalies (Fig. 8-1). Although these data are from women with severe overt diabetes, the incidence of fetal anomalies in women who have gestational diabetes with fasting hyperglycemia is increased fourfold compared with that in normal women (Sheffield, 2002).

FIGURE 8-1 Relationship between first-trimester glycosylated hemoglobin values and risk for major congenital malformations in 320 women with insulin-dependent diabetes. (Data from Kitzmiller, 1991.)

Such counseling has been shown to be effective. In one review, Leguizamón and associates (2007) identified 12 studies that included more than 3200 pregnancies in women with insulin-dependent diabetes. Of the 1618 women without preconceptional counseling, 8.3 percent had a fetus with a major congenital anomaly, and this compared with a rate of 2.7 percent in the 1599 women who did have counseling. Tripathi and coworkers (2010) compared outcomes in 588 women with pregestational diabetes in whom about half had preconceptional counseling. Those women who received counseling had improved glycemic control before pregnancy and in the first trimester, had higher folate intake rates preconceptionally, and experienced lower rates of adverse outcomes—defined as a perinatal death or major congenital anomaly. These cited benefits are accompanied by reduced health-care costs in diabetic women. From their review, Reece and Homko (2007) found that each $1 expended for a preconceptional care program saved between $1.86 and $5.19 in averted medical costs. Despite such benefits, the proportion of diabetic women receiving preconceptional care is suboptimal. In their study of approximately 300 diabetic women in a managed-care plan, Kim and colleagues (2005) found that only about half had preconceptional counseling. Counseling rates are undoubtedly much lower among uninsured and indigent women.

Epilepsy

Epilepsy

Women who have epilepsy have an undisputed two- to threefold risk of having infants with structural anomalies compared with unaffected women (Wide, 2004). Some early reports indicated that epilepsy conferred an increased a priori risk for congenital malformations that was independent of any effects of anticonvulsant treatment. Although more recent publications have largely failed to confirm this increased risk in untreated women, it is difficult to refute entirely because women who are controlled without medication generally have less severe disease (Cassina, 2013). Fried and associates (2004) conducted a metaanalysis of studies comparing epileptic women, both treated and untreated, with controls. In this study, increased malformation rates could only be demonstrated in the offspring of women who had been exposed to anticonvulsant therapy. Veiby and coworkers (2009) used the Medical Birth Registry of Norway to compare pregnancy outcomes in 2861 deliveries by epileptic women with 369,267 control deliveries. They identified an increased malformation risk only in women who were exposed to valproic acid (5.6 percent) and polytherapy (6.1 percent). Untreated women had anomaly rates that were similar to those of nonepileptic controls.

Ideally, seizure control is optimized preconceptionally. Vajda and colleagues (2008) reported data from the Australian Register of Antiepileptic Drugs in Pregnancy. The risk of seizures during pregnancy was decreased by 50 to 70 percent if there were no seizures in the year preceding pregnancy. There were no further advantages that accrued if the seizure-free period exceeded a year.

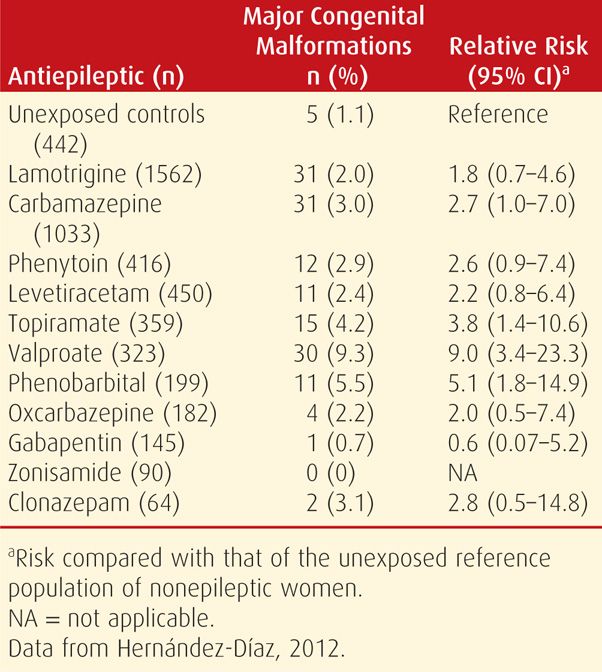

Efforts should attempt to achieve seizure control with monotherapy and with medications considered less teratogenic (Aguglia, 2009; Tomson, 2009). As discussed in detail in Chapter 60 (p. 1190) and shown in Table 8-2, some one-drug regimens are more teratogenic than others. Valproic acid, in particular, should be avoided if possible, as this medication has consistently been associated with a greater risk for major congenital malformations than other antiepileptic drugs (Jentink, 2010). According to Jeha and Morris (2005), the American Academy of Neurology recommends consideration of antiseizure medication discontinuation before pregnancy in suitable candidates. These are women who satisfy the following criteria: have been seizure-free for 2 to 5 years, display a single seizure type, have a normal neurological examination and normal intelligence, and show electroencephalogram results that have normalized with treatment.

TABLE 8-2. First-Trimester Antiepileptic Monotherapy and the Associated Congenital Malformation Risk

Epileptic women should be advised to take supplemental folic acid. However, it is not entirely clear that folate supplementation reduces the fetal malformation risk in pregnant women taking anticonvulsant therapy. In one case-control study, Kjær and associates (2008) reported that the congenital abnormality risk was reduced by maternal folate supplementation in fetuses exposed to carbamazepine, phenobarbital, phenytoin, and primidone. Conversely, from the United Kingdom Epilepsy and Pregnancy Register, Morrow and coworkers (2009) compared fetal outcomes of women who received preconceptional folic acid with those who did not receive it until later in pregnancy or not at all. In this study, a paradoxical increase in the number of major congenital malformations was observed in the group who received preconceptional folate. These investigators concluded that folate metabolism may be only a part of the mechanism by which malformations are induced in women taking these medications.

Immunizations

Immunizations

Preconceptional counseling includes assessment of immunity against common pathogens. Also, depending on health status, travel plans, and time of year, other immunizations may be indicated as discussed in Chapter 9 (Table 9-9, p. 186). Vaccines that contain toxoids—for example, tetanus, or that consist of killed bacteria or viruses—such as influenza, pneumococcus, hepatitis B, meningococcus, and rabies—have not been associated with adverse fetal outcomes and are not contraindicated preconceptionally or during pregnancy. Conversely, live-virus vaccines—including varicella-zoster, measles, mumps, rubella, polio, chickenpox, and yellow fever—are not recommended during pregnancy. Moreover, 1 month or longer should ideally pass between vaccination and conception attempts. That said, inadvertent administration of measles, mumps, rubella (MMR) or varicella vaccines during pregnancy should not generally be considered indications for pregnancy termination. Most reports indicate that the fetal risk is only theoretical. Immunization to smallpox, anthrax, and other bioterrorist diseases should be discussed if clinically appropriate (Chap. 64, p. 1258). Based on their study of approximately 300 women who received smallpox vaccination near the time of conception, Ryan and colleagues (2008) found that rates of pregnancy loss, preterm birth, and birth defects were not higher than expected.

GENETIC DISEASES

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2013) estimate that 3 percent of neonates born each year in the United States will have at least one birth defect. Importantly, such defects are the leading cause of infant mortality and account for 20 percent of deaths. The benefits of preconceptional counseling usually are measured by comparing the incidence of new cases before and after initiation of a counseling program. Congenital conditions that clearly benefit from patient education include neural-tube defects, phenylketonuria, thalassemias, and other genetic diseases more common in individuals of Eastern European Jewish descent.

Family History

Family History

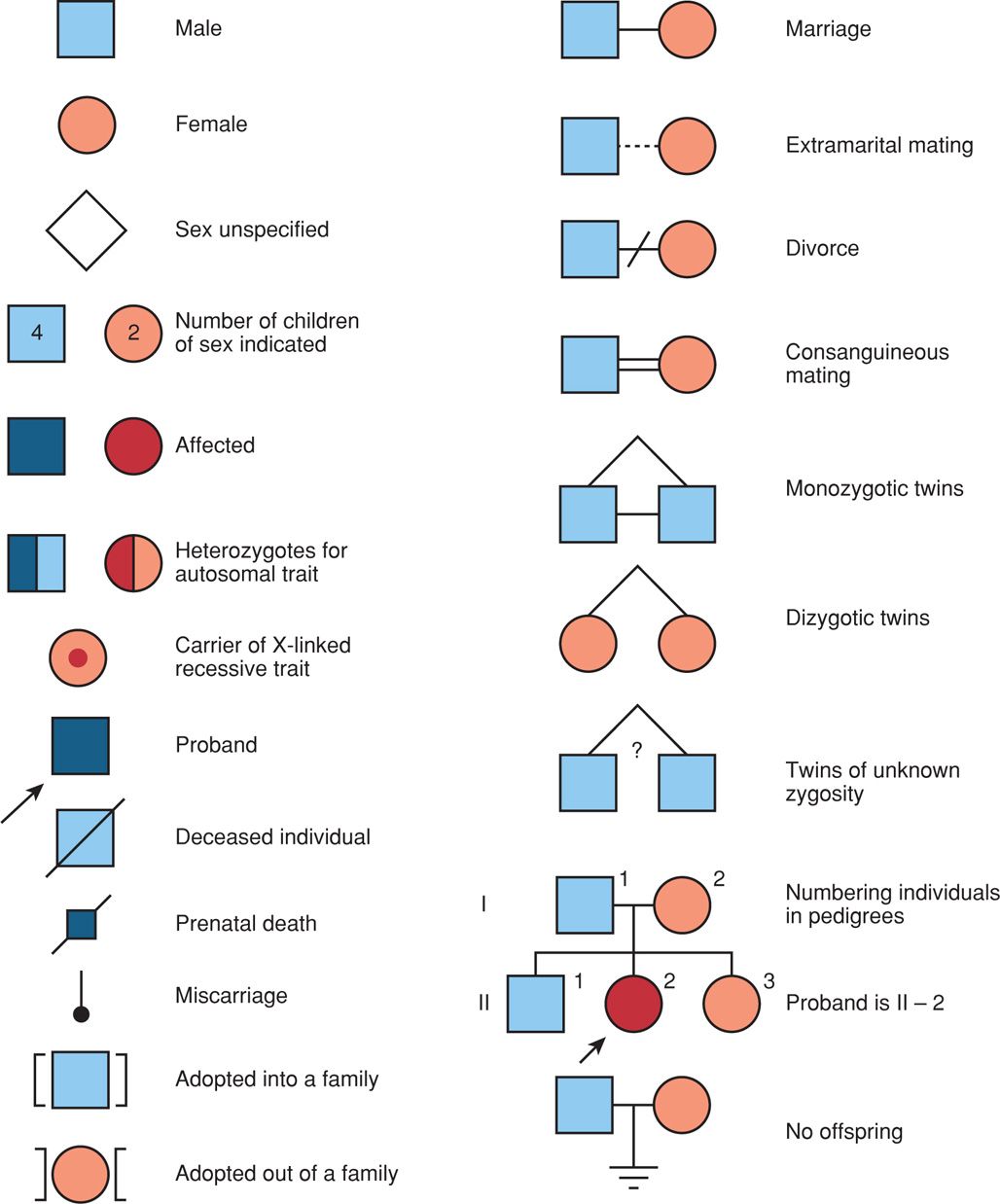

Pedigree construction using the symbols shown in Figure 8-2 is the most thorough method for obtaining a family history as a part of genetic screening. The health and reproductive status of each “blood relative” should be individually reviewed for medical illnesses, mental retardation, birth defects, infertility, and pregnancy loss. Certain racial, ethnic, or religious backgrounds may indicate increased risk for specific recessive disorders.

FIGURE 8-2 Symbols used for pedigree construction. (Redrawn from Thompson, 1991.)

Although most women can provide some information regarding their history, their understanding may be limited. For example, several studies have shown that pregnant women often fail to report a birth defect in the family or they report it incorrectly. Thus, any disclosed defect or genetic disease should be confirmed by reviewing pertinent medical records or by contacting affected relatives for additional information.

Neural-Tube Defects

Neural-Tube Defects

The incidence of neural-tube defects (NTDs) is 0.9 per 1000 live births, and they are second only to cardiac anomalies as the most frequent structural fetal malformation (Chap. 14, p. 283). Some NTDs, as well as congenital heart defects, are associated with specific mutations. One example is the 677C → T substitution in the gene that encodes methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase. For this and similar gene defects, the trial conducted by the Medical Research Council Vitamin Study Research Group (1991) showed that preconceptional folic acid therapy significantly reduced the risk for a recurrent NTD by 72 percent. More importantly, because more than 90 percent of infants with NTDs are born to women at low risk, Czeizel and Dudas (1992) showed that supplementation reduced the a priori risk of a first NTD occurrence. It is currently recommended, therefore, that all women who may become pregnant take 400 to 800 μg of folic acid orally daily before conception and through the first trimester (U.S Preventive Services Task Force, 2009). Folate fortification of cereal grains has been mandatory in the United States since 1998, and this practice has also resulted in decreased neural-tube defect rates (Mills, 2004). Despite the demonstrated benefits of folate supplementation, only half of women have taken folic acid supplementation periconceptionally (de Jong-van den Berg, 2005; Goldberg, 2006). The strongest predictor of use appears to be consultation with a health-care provider before conception.

Phenylketonuria

Phenylketonuria

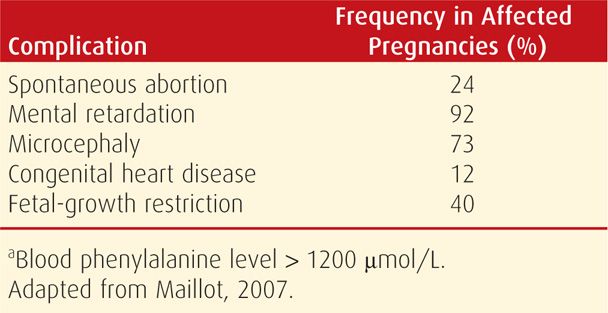

This inherited phenylalanine metabolism defect exemplifies diseases in which the fetus may not be at risk to inherit the disorder but may be damaged by maternal disease. Specifically, mothers with phenylketonuria (PKU) who eat an unrestricted diet have abnormally high blood phenylalanine levels. This amino acid readily crosses the placenta and can damage developing fetal organs, especially neural and cardiac tissues (Table 8-3). With appropriate preconceptional counseling and adherence to a phenylalanine-restricted diet before pregnancy, the incidence of fetal malformations is dramatically reduced (Guttler, 1990; Hoeks, 2009; Koch, 1990). It is recommended, therefore, that the phenylalanine concentration be normalized 3 months before conception and that these levels be maintained throughout pregnancy (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2009b).

TABLE 8-3. Frequency of Complications in the Offspring of Women with Untreated Phenylketonuriaa (Blood Phenylalanine > 1200 μmol/L)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree