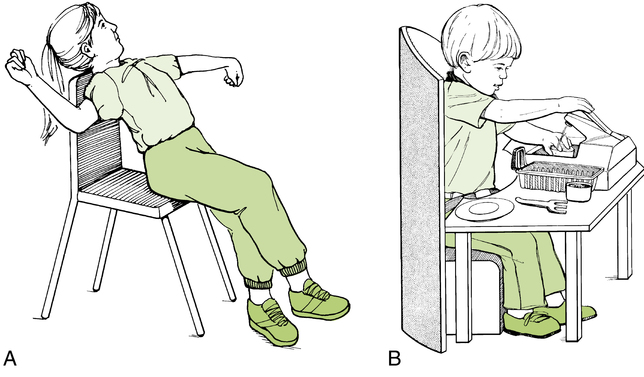

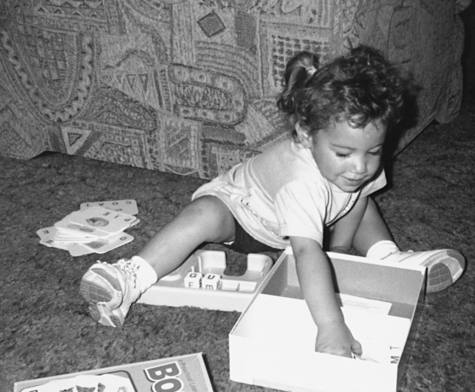

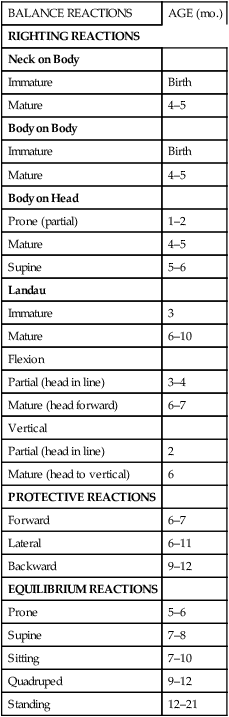

17 LISA BAILLARGEON, KATHERINE MICHAUD, KATIE FORTIER and CHOU-HSIEN LIN After studying this chapter, the reader will be able to accomplish the following: • Describe the variety of positions and transitional movements children use in typical development • Describe the characteristics of developmental positions • Identify equipment that positions children so they may engage in their daily occupations • Identify positioning and handling techniques occupational therapy (OT) practitioners use in intervention with children and adolescents • Explain the key concepts and principles of neurodevelopmental treatment (NDT) • Distinguish between positioning and handling techniques • Understand the application of therapeutic positioning and handling principles and techniques exemplified through case examples Positioning is important toward developing postural stability, but it is also required for children to participate in daily occupations. When the skeletal system is aligned and children are positioned symmetrically, each side of the body develops adequate muscle strength needed for postural stability. Symmetrical alignment helps children maintain the full range of motion (ROM) for movement. Therefore, symmetrical positioning with head, neck, trunk, and pelvis aligned, allows children to move the arms and legs efficiently, bring the hands to midline to work with objects, and maneuver the legs. Positioning children symmetrically provides physical comfort, reduces fatigue, and promotes stability so that they may engage in occupations such as feeding, dressing, and playing. Thus, one of the first principles of positioning is to make sure that children are symmetrical and well aligned. OT practitioners may use positioning devices to support children in symmetrical positions. Often providing external support helps children maintain a position to perform daily occupations (Figure 17-1). Changing positions stimulates different sensory experiences. For example, weight bearing on hands provides infants with tactile sensations and experiences that are important for later hand development. Children develop body awareness as they experience proprioceptive feedback from their muscles and joints about where their bodies are in space. As children develop the ability to sit upright, they see things at different angles; they feel different sensations; and they develop a sense of balance, which helps promote postural stability for mobility and functional activity (Figure 17-2). Maintaining positions requires postural control, which refers to the ability to sustain the necessary trunk control to use the arms, hands, and legs and efficiently carry out skilled tasks, such as playing, coloring, or feeding. See Box 17-1 for a description of the relationship between stability and mobility. Along with adequate muscle tone and skeletal alignment, children need a sense of balance to maintain postural control. Balance, also referred to as postural stability, refers to the ability to maintain the center of gravity over the base of support. The center of gravity is the point where the total body weight is most evenly distributed over the base of support. The center of gravity is also referred to as the center of mass when it relates to the child’s center of distribution. Children must first sense changes in the center of mass before they are able to respond to these changes. Children respond to changes in balance through righting and equilibrium reactions. Righting reactions are those reactions that bring the body back to midline position and are defined as the maintenance of the proper alignment of the head and trunk in space. For example, righting reactions are present as an infant moves his head upright and vertical when tilted to the side (righting the head on the neck). Another example of righting reactions is when the head, trunk, and pelvis rotate on an axis, as seen in rolling to maintain alignment of the body segments (head, trunk, pelvis). This is observed as infants turn their bodies in alignment to roll toward a toy. An infant develops head righting reactions in the first few months of life in response to visual and vestibular sensory input. Equilibrium reactions help one maintain balance when the body’s center of mass is shifted too far over the base of support. Equilibrium reactions may require the use of the head, trunk, arms, and legs to flex or abduct in order to adjust the body’s center of mass over the base of support to prevent a fall. The maturation of equilibrium reactions occurs in an orderly sequence—prone, supine, sitting, quadruped, and standing—as the infant gains antigravity muscle strength and postural control (Figure 17-3). Equilibrium reactions may also involve subtle changes in muscle tone to maintain position. For example, equilibrium reactions can be observed as a child maintains balance when standing on one foot. This involves subtle adjustments in muscle tone to maintain the upright position. Protective extension reactions occur when the body’s center of mass is shifted too far off the base of support and righting and equilibrium reactions cannot bring the body back to midline. They involve extending an arm or a leg forward to “save face” when the change in balance is so extreme that children feel unable to correct their position to avoid falling. Protective extension can be observed as a child quickly places a hand on the floor to catch himself or herself when pushed off balance suddenly. (Refer to Table 17-1 for a description of the development of postural reactions.) TABLE 17-1 From Case-Smith J, O’Brien J: Occupational therapy for children, ed 6, St. Louis, 2010, Mosby. The principles of positioning children include the following: • Providing the child with a variety of positioning options throughout the day • Placing the child in positions that enhance function • Avoiding positions that restrict the child’s movement • Providing positions that are comfortable for the child. • Considering safety when prescribing positions (e.g., do not leave a child unattended in a positioning device) • Ensuring proper skeletal alignment and symmetry during positioning of the child • Recommending positioning equipment that provides external stability to facilitate movement

Positioning and handling: a neurodevelopmental approach

General considerations

Skeletal alignment

Perception and body awareness

Postural control for balance and functional activity

BALANCE REACTIONS

AGE (mo.)

RIGHTING REACTIONS

Neck on Body

Immature

Birth

Mature

4–5

Body on Body

Immature

Birth

Mature

4–5

Body on Head

Prone (partial)

1–2

Mature

4–5

Supine

5–6

Landau

Immature

3

Mature

6–10

Flexion

Partial (head in line)

3–4

Mature (head forward)

6–7

Vertical

Partial (head in line)

2

Mature (head to vertical)

6

PROTECTIVE REACTIONS

Forward

6–7

Lateral

6–11

Backward

9–12

EQUILIBRIUM REACTIONS

Prone

5–6

Supine

7–8

Sitting

7–10

Quadruped

9–12

Standing

12–21

Positioning as a therapuetic tool

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Positioning and handling: a neurodevelopmental approach

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue