84 Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome

Etiology and Pathogenesis

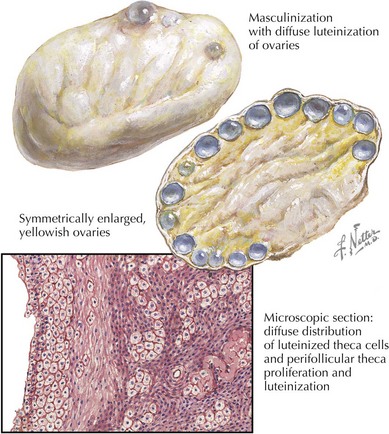

PCOS is thought to result from an interaction involving multiple genetic loci and environmental factors that disrupt several metabolic pathways. Resulting androgen excess can present as hyperandrogenism (Figure 84-1). One androgen pathway involved in PCOS is altered luteinizing hormone (LH) function, which can lead to increased androgen production by ovarian theca cells. This finding is especially common in thin or normal weight women with PCOS. Another potential pathway that leads to elevated androgens involves insulin resistance and compensatory hyperinsulinemia. Elevated insulin levels can also stimulate androgen production by ovarian theca cells while simultaneously inhibiting liver synthesis of sex hormone–binding globulin (SHBG), which in turn results in an increased fraction of bioavailable or free testosterone.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>