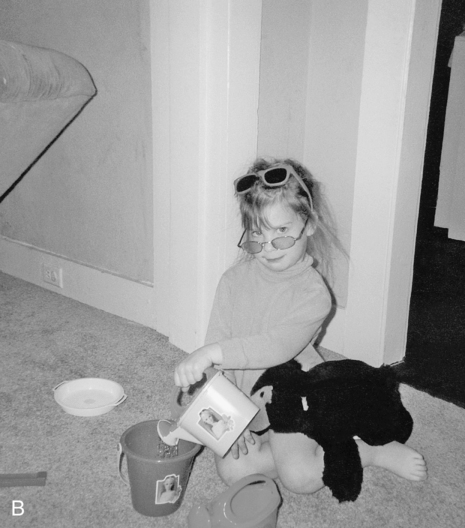

20 JANE CLIFFORD O’BRIEN and GWENDOLYN J. DUREN After studying this chapter, the reader will be able to accomplish the following: • Describe the characteristics of play and playfulness and differentiate between the two • Identify potential barriers to play that children with disabilities may encounter • Describe ways to facilitate play and playfulness in children who have special needs • Describe the way that play is used as a tool in occupational therapy sessions to increase skills • Describe how play is used as a goal of occupational therapy • Identify occupational therapy assessments used to evaluate play and playfulness Children learn and refine skills during play.1,5,6,17,20,27 This is demonstrated as children show off feats of strength and agility, problem-solve to play a game or perform a motor skill, and work out problems that arise. They communicate to satisfy their needs and decide on rules for the activities by negotiating with group members. Often children spend the entire play time deciding on the rules of the game or the way the story will unfold. They use their language skills and must become keen observers of nonverbal communication.6,10 Maximizing a child’s ability to play interests occupational therapy (OT) practitioners because it is the primary occupation of childhood and critical to the development of skills.10,28,36 To appreciate the importance of play, imagine life without it. Life would certainly be lacking without play. Parham and Primeau underscored the importance of play by stating that it may reveal what makes life worth living.42 Play is generally defined as a pleasurable, self-initiated activity that the child can control. Intrinsic motivation is the self-initiation or drive to action for which the reward is the activity itself rather than some external reward.10 Intrinsic motivation is demonstrated when children repeat activities over and over.10 Internal control is the extent to which the child is in control of the actions and to some degree the outcome of an activity.10 Internal control is observed when children spontaneously change the play (e.g., when a 6-year-old boy declares in the middle of a pretend game, “Now I am going to be the good guy.”). Intrinsic motivation and internal control are important for the development of problem solving, learning, and socialization skills. Another element of play is the freedom to suspend reality, which is sometimes seen as the ability to participate in make-believe activities, or pretend play (Figure 20-1).10,49 Pretend play develops as children are able to engage in higher cognitive functioning.46 They begin by role playing simple everyday actions such as feeding a doll. They are able to engage in elaborate make-believe scenarios as their language and cognitive skills develop. Freedom to suspend reality also includes teasing, joking, mischief, and bending the rules.10 Children turn old games into new ones by changing the rules, creating new situations, and using objects imaginatively during play. Play is the primary occupation of children and a medium for intervention.11,23,27,35,40,41 Playfulness is defined as one’s disposition to play.5,11 It is a style individuals use to flexibly approach problems and can be regarded as an aspect of a child’s personality.11 Playfulness, like play, encompasses intrinsic motivation, internal control, and freedom to suspend reality, all of which occur on a continuum.10,23,33,36 Children who are engaged in the play process are intrinsically motivated. They show signs of enjoyment and seem to be having fun.10,14 Internal control is evidenced in sharing, playing with others, entering new play situations, initiating play, deciding, modifying activities, and challenging themselves.10,14 Children who use objects creatively or in unconventional ways, tease, and pretend show the element of freedom to suspend reality (Figure 20-2).10,14 OT practitioners must understand the nature of play and playfulness in order to use it effectively as an intervention technique. When children play and are playful, depending on the activity, they may laugh, smile, and be active; they may also be serious, quiet, and totally absorbed in play (Figure 20-3). Play can be frustrating, and it can involve failures. The flexible and spontaneous nature of play and playfulness is demonstrated when children change themes or use toys in unexpected ways. The process (doing) rather than the product (outcome) provides the primary source of reward in play activities.10 Children engage in play for its own sake.11,14 Playful children discover, create, and explore. Therefore, no way of playing is right or wrong. Play is a safe outlet for children to challenge themselves and helps them develop skills. OT practitioners must remember to maintain the nature of play and playfulness during therapy. Children who have special needs may require additional assistance to play.32,44 OT practitioners are knowledgeable about the abilities of children who have special needs and are therefore in an ideal position to promote play and playfulness. The normal sequence for the development of play is often delayed in children who have special needs.25,27,30,32,34,37 (See Chapter 7 for a discussion of this sequence.) This may be the result of limited physical, cognitive, or social–emotional skills.27,30,34 For example, a child who is unable to bring the hands to the mouth has trouble exploring the environment. Children who are unable to experience sensations in a typical manner often require intervention to engage in play opportunities, which stimulate their growth and development. If children are not afforded these opportunities, they may exhibit poor play skills.34,38,44 Changing or modifying the environment (such as modifying the playground for wheelchair access) helps children who have special needs experience play.34,37,38 Children who have special needs may take longer to respond, make less obvious responses, initiate activities less frequently, and be less interactive than other children.32,37 They are often passive in their play.30,32,34 Children with intellectual deficits exhibit a restricted repertoire of play and language, decreased attention span, and less social interaction during play.30,32,34 Children with visual impairments are less interested in reaching out to explore and engage in social exchanges during play.30 Children with hearing impairments show less symbolic and less organized play.30 Children who have developmental and physical disabilities commonly experience difficulty playing. They do not have the same play skills as their typically developing peers, and therefore are not exposed to the same play opportunities. These barriers are believed to correlate with deficits in other areas of the child’s development such as social and emotional, speech, gross motor, creativity, and problem-solving abilities. Children with disabilities often receive interventions for their diagnosed disabilities and their presenting symptoms; unfortunately, most interventions rarely focus on play.29 Children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) commonly experience difficulty engaging in cooperative play.21 They tend to play for shorter periods of time, frequently change their play activity, and have difficulty returning to an activity after an interruption.15 In structured play settings, children with ADHD often experience trouble transitioning from one activity to another and display more negative play behaviors (such as disrupting and violating established play rules).21 Cordier et al studied children with ADHD to determine how to effectively design a play-based intervention model.21 They focused on the typical behaviors of children with ADHD, their play environments, and motivating these children. The impulsive and hyperactive behavior in conjunction with poor self-regulation and control may also create deficits in a child’s intrinsic control and motivation, a foundational component of play. They suggested that OT practitioners use a client-centered approach to design interventions for children with ADHD focusing on improving their socials skills and reducing tendencies of disruption and domination.21 Children with autistic disorders display deficits in communication abilities, social interactions, and range of interests and activities. They show limited socialization and imagination, which interferes with play. They tend to prefer playing alone, and when in groups, they commonly have difficulty detecting and understanding the meaning of verbal and nonverbal social cues displayed by the other children.48 To successfully promote play, OT practitioners strive to create interventions that are both appealing and motivating to the child. Children with sensory processing disorder (SPD) and those with developmental coordination disorder (DCD; see Chapters 12 and 24 for explanations of these conditions) may have difficulties with play and playfulness.15,19 These children may benefit from play environment adaptations and focus on their ability to play. SPD often interferes with a child’s ability to interact with people and objects in his or her environment. Children with DCD experience gross motor delays. Furthermore, once they have mastered tasks, they repeatedly perform the tasks with little variation and show limited flexibility in their movement patterns.15 Children with SPD also often exhibit limited variability in movements. With respect to play, this lack of variability or flexibility causes less interest in play and participation in play groups. Bundy et al found that for children with SPD, changing the play setting seems to have more effect on play capabilities than does focusing on remediating praxis (e.g., motor planning).15 For example, modifying a child’s environment to better stimulate interest and inspire confidence may promote expansion of social play skills. Improving social skills and confidence through play may lead to parallel developments in other areas of a child’s life and learning experiences.48 Children with cerebral palsy (CP) display impaired postural control and functional ambulation, which can be accompanied by emotional and behavioral dysfunction.47 (See Chapter 16.) This condition affects both physical and cognitive development, including communication skills, and is present over an individual’s lifespan. These functional impairments may create significant barriers to a child’s development of playfulness. Modifying the play environment by reducing physical barriers helps increase playfulness in children who have CP.13 Improving communication with parents can also positively influence playfulness.13 Children who have special needs require assistance in order to meet developmental challenges and learn ways to play.26,30,32,34,37 OT practitioners must understand typical play patterns and support these children when teaching skills and facilitating play. For example, OT practitioners can increase spontaneity in children by allowing them to discover play materials that have been hidden or placed within reach.18,34,37,44 OT practitioners must identify these children’s strengths and weaknesses, as well as those of the family, to design effective interventions. Capitalizing on strengths can increase the success of therapy and facilitate development of advanced play skills. The environment in which play occurs influences children’s play. Each child has his or her own unique style of play, which is shaped by age, gender, experiences, family, and environment.4 Engaging in play depends on a child’s feeling of safety, confidence, and interests. Therefore, a child’s environment may promote or restrict playfulness.7,16,48 For example, structuring of school days and the availability of staff members have influenced play environments and opportunities for children. Currently, many schools have restricted the allotted time for outdoor recesses and have removed equipment from playgrounds. In the past, children commonly played outdoors in wooded areas or cleared fields and mostly did not play with manufactured toys, which promoted social interactions, imaginative play, creativity, and physical activity.13 Bundy suggested that parental responses to safety concerns have reduced the opportunities for children’s play in imaginative and creative ways.13 For example, parents and teachers promote the “correct way” to go down a slide. Children commonly play on playgrounds—play environments with static play equipment (slides, swings, climbers, etc.) that do not lend themselves to nearly as much imaginative play and creative manipulation.12,13 For children with physical disabilities, playgrounds can create a barrier to cooperative play with their typically developing peers. It is important for an OT practitioner to consider a child’s environment when assessing play and playfulness. Models such as the Model of Human Occupation and Person–Environment–Occupation (PEO) examine how the physical or social environment supports or inhibits a child’s play.16,28 Interventions focusing on changing or modifying environmental factors can promote play skills.

Play and playfulness

Play

Playfulness

Nature of play and playfulness

Play development of children with disabilities

Influence of environment on play

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree