Introduction

Placenta accreta is defined as an abnormally firm attachment of placental villi to the uterine wall with the absence of the normal intervening decidua basalis and fibrinoid layer of Nitabuch. Collectively termed “placenta accreta,” three variants of the condition are recognized. In the most common form, accreta, the placenta is attached directly to the myometrium. This variant accounts for approximately 75–78% of all cases. In approximately 17% of cases, the placenta extends into the myometrium and is termed placenta increta. In the remaining 5–7%, the placenta extends through the entire myometrial layer and is termed placenta percreta.

Over the past two decades, the reported incidence of placenta accreta has ranged from 1 in 533 to 1 in 2510 deliveries [1,2]. The latter incidence reflects the observed number of histologically confirmed placenta accreta cases from 1985 to 1994 at the University of Southern California. These numbers are considerably higher than what has been reported in the past. A major contributor to this rise appears to be the increasing incidence of previous cesarean delivery.

A characteristic feature of placenta accreta is the absence or attenuation of the decidua basalis. This abnormality permits the trophoblasts to come into direct contact with, and invade into, the underlying myometrium. The resultant abnormally firm placental attachment prevents the placenta from separating normally after delivery and interferes with uterine contraction that is essential to postpartum hemostasis. In the majority of cases placenta accreta remains asymptomatic until delivery. Although antepartum hemorrhage is not uncommon, it is more likely attributable to placenta previa which often accompanies it than to placenta accreta itself.

Intractable hemorrhage and the operative procedures performed in an attempt to control the bleeding are the major sources of maternal morbidity and mortality in cases of placenta accreta. Subsequently, additional complications can occur such as hysterectomy, ureteral/bladder injury, visceral injury, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, ARDS, renal failure, and death. In a review of 109 cases of placenta percreta, O’Brien et al. reported 44 cases (40%) requiring greater than 10 units of blood transfusion, five cases (5%) with ureteral ligation or fistula formation, 31 cases (28%) of infection, 10 cases (9%) of perinatal death, and eight cases (7%) of maternal death. Of particular interest were the three cases of uterine rupture [3]. The blood loss from such cases is considerable. At the University of Southern California, among 62 cases of placenta accreta the estimated blood loss exceeded 2000 mL in 41 cases (66%), 5000 mL in nine (15%), 10,000 mL in four (6.5%), and 20,000 mL in two (3%). Thirty-two women (55%) required blood transfusions. Blood product replacement exceeded 5 units in 13 (21%), 20 units in five (8%), and 70 units in three (5.5%). Three cases required ureteral transaction and reimplantation or reanastomosis. Additional morbidity included disseminated intravascular coagulation (five), hypotensive shock (two), reoperation from control of hemorrhage (two), and enterotomy (one) [4]. There were no maternal deaths [1].

The principal perinatal complication of placenta accreta is prematurity. O’Brien et al. reported that among 109 cases of placenta percreta, there were 10 perinatal deaths. Six of the 10 cases were due to extreme prematurity with a median gestational age of 22 weeks and two were associated with concomitant maternal death [3]. Alternatively, among 62 cases of placenta accreta at the University of Southern California, there were no perinatal deaths. This may be attributed to the mean gestational age at delivery which was 34.6 weeks.

Several risk factors for placenta accreta have been identified (Box 16.1). Among these, the two most important appear to be prior cesarean delivery and placenta previa. Placenta accreta complicated 9.3% of 590 cases of placenta previa at the University of Southern California from 1985 to 1994. Among 155,080 women without placenta previa, the incidence of placenta accreta was 1 in 22,154. In women with placenta previa, the incidence of placenta accreta appears to correlate with the number of previous cesarean sections. Clark et al. reported a 5% incidence of placenta accreta among women with placenta previa and no previous cesarean sections [5]. The incidence increased to 24% with one previous cesarean section and to 45% with two or more. Among 723 women with cesarean delivery and previa, Silver et al. reported the risk for accreta to be 3%, 11%, 40%, 61%, and 67% for one, two, three, four, and five or more cesarean deliveries. Among 29,409 women with cesarean delivery and no previa, the risk for accreta was 0.03%, 0.2%, 0.1%, 0.8%, 0.8%, 4.7% for one, two, three, four, five, and six or more cesarean deliveries [6].

Box 16.1 Risk factors for placenta accreta

- Placenta previa

- Previous cesarean section

- Advanced maternal age

- Placental location with respect to uterine scar

- Multiparity

- Previous uterine curettage

- Previous myomectomy

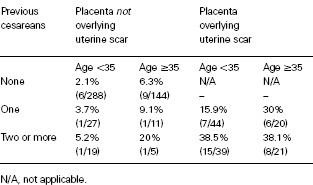

Table 16.1 Estimated risk of placenta accreta among women with placenta previa

Advanced maternal age and placental location with respect to the previous uterine scar also have been reported to be independent risk factors for placenta accreta among women with placenta previa. Miller reported a 2.1% incidence of accreta in women with placenta previa who were less than 35 years of age and had no previous cesareans. The incidence increased to 38.1% in women who were 35 years of age or older with two or more previous cesarean sections and a placenta previa overlying the uterine scar (Table 16.1

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree