Chapter 5 Physical Examination

What Is Important in the Physical Examination?

The content of the physical examination depends on the patient’s age, developmental stage, and the reason for the evaluation. Table 5-1 lists age-specific physical examination components. In general, a health supervision visit, a hospital admission, or the assessment of a complex complaint demands a comprehensive examination. Assessment of the daily progress of a hospitalized patient or the evaluation of a specific problem for a patient in a clinic will typically require an examination focused on the systems involved. Use of resources such as those listed in the reference section will greatly expand your knowledge of physical findings in infants, children, and adolescents.

Table 5-1 Age and Developmental Stage–Related Focus for Physical Examination

| Age | Focus |

|---|---|

| Newborn (see Chapter 14) | Assessment of gestational age |

| Determination of appropriateness of size for gestational age | |

| Identification of birth injuries and congenital anomalies | |

| Diagnosis of acute neonatal illnesses | |

| Infant | Assessment and monitoring of growth, development, and temperament |

| Late manifestations of congenital anomalies or delayed sequelae of neonatal problems | |

| Tympanic membranes, emergence of teeth | |

| Signs of abuse | |

| For an ill infant: Observe skin color, perfusion, hydration, and oxygenation; assess respiratory effort, level of consciousness, social interaction, and quality of the cry | |

| Toddler | Assessment and monitoring of growth and of developmentalprogress |

| Observation of behavior and child-parent interactions | |

| Gait, dentition, vision, hearing (middle ear status), and bloodpressure (after age 3) | |

| Signs of abuse | |

| School-age | Assessment and monitoring of growth, including body mass index (BMI) |

| Signs of puberty: girls after age 7 or 8 and boys after age 9 | |

| Dentition, development, behavior, blood pressure, vision, hearing, and scoliosis | |

| Focus on patient concerns | |

| Signs of abuse | |

| Adolescent (see Chapter 15) | Assessment and monitoring of growth, including BMI, and puberty |

| Breast self-examination for girls and testicular self-examination for boys | |

| Blood pressure, acne, dentition, signs of abuse | |

| Acute or chronic illness concerns | |

| Mental status observations |

VITAL SIGNS, APPEARANCE, AND BEHAVIOR

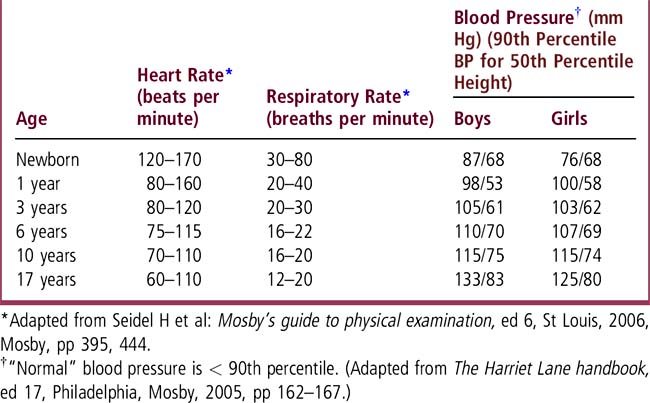

Review vital signs and compare them with age-specific reference data (Table 5-2). “Normal” vital signs are age (and often sex and size) specific. “Normal” blood pressure (BP) is below the 90th percentile for age, sex, and height. Hypertension is defined as persistent BP readings above the 95th percentile for age, sex, and height. BP is discussed in Chapter 46. Use growth charts to assess height, weight, body mass index (BMI), and head circumference. Pay attention to symmetry of growth, morphologic features, development, behavior, and the patient’s interaction with parents and the examiner. Observe mental status in older children and adolescents. When evaluating an acute illness, look for disease-specific signs plus evidence of shock or toxicity, such as skin color, respiratory effort, hydration status (capillary refill), mental status, cry, and interactions. Chronic illness may result in growth abnormalities, system/organ-specific dysfunction, or other characteristic findings. A patient’s appearance and physical findings may reflect a pattern of malformation that is characteristic of a syndrome or other identifiable cause of structural defects (see Chapter 62).

HEAD, EYES, EARS, NOSE, AND THROAT (HEENT)

HEAD

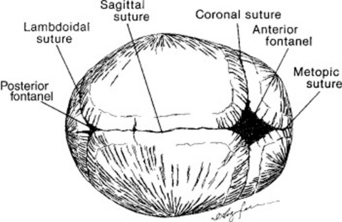

Measure head size and plot the data on the growth chart. Head circumference increases steadily from an average of 34 cm at birth to 48 cm (girls) and 49 cm (boys) by age 2; it then increases more slowly until the mean adult value of 55 cm (female) and 56 cm (male) is reached. Look at head shape and symmetry, facial features, and hair whorls. Identify the sutures and fontanels in an infant (Figure 5-1 and Chapter 14); these are usually not palpable after 15 to 18 months, occasionally earlier. The anterior fontanel is diamond shaped and at birth is approximately 2 × 2 cm (range 1 × 1 to 3 × 4 cm). The posterior fontanel is usually not palpable, even at birth, but when open it is the size of a small fingertip (< 1 × 1 cm). The superior surface of the anterior fontanel is generally level with the surface of the skull. Marked ridging or bony prominence of sutures in young infants may reflect premature fusion (synostosis). Widely separated sutures may reflect increased intracranial pressure and may be accompanied by a bulging and enlarged anterior fontanel. To determine whether the fontanel is bulging, move the infant to a sitting position, inspect the fontanel, then run your fingers across the fontanel surface. If the fontanel protrudes convexly beyond the skull’s surface, it is bulging. Dehydrated infants often display a sunken fontanel, concave with respect to the skull surface.

Figure 5-1 Cranial sutures and fontanels.

From Seidel HM et al: Mosby’s guide to physical diagnosis, ed 6, Philadelphia, 2003, Mosby, p 258.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree