13 Physical Activity and Sports for Children and Adolescents

Physical Activity: Definition and Surveillance Data

Physical Activity: Definition and Surveillance Data

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC):

• High school students doing any kind of physical activity that increased heart rates more than usual for 60 or more minutes per day at least 5 days per week

• Attending school physical education (PE) class at least 1 to 5 days in a school week

• Percentages of middle or junior high schools or high schools requiring daily PE

Further data analysis reveals that:

• Physical activity rates decreased for all students as they progressed through high school (i.e., rates of physical activity were highest for ninth graders and decreased through twelfth grade). This was true in 2007 and 2009 (Eaton et al, 2010).

• Attendance in a PE class was higher for males than for females (USDHHS, 2008b).

• In 1969, approximately 42% of American children walked or cycled to and from school, compared with only about 16% in 2001 and about 14% in 2008. Concern with vehicular speed and other safety issues were cited by parents as reasons they discouraged such active transportation by their children, even when they lived within less than two miles of the school (U.S. Department of Transportation [USDOT], 2008, 2010).

• Between 2003 and 2009 there was a significant linear rise in the amount of recreational computer/video game hours; between 1999 and 2009, there was a significant linear decrease in television time (Eaton et al, 2010).

• Between 2007 and 2009, there have been no statistically significant increases in physical activity behaviors; females remain less likely to have been physically active than males (Eaton et al, 2010).

Promoting Physical Activity: Guidelines and Standards

Promoting Physical Activity: Guidelines and Standards

2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans

• Children and adolescents should strive for 60 minutes of physical activity daily; the minutes do not necessarily need to be contiguous.

• Physical activity should be of moderate to vigorous levels.

• Physical activity should include each of the following on 3 or more days per week:

• Physical activity should be enjoyable to the child/adolescent and developmentally appropriate.

• In becoming more physically active, a child or adolescent who was previously inactive should increase time and intensity gradually.

• Any level of physical activity is better than none at all.

Healthy People 2010 and 2020

1. Increase the proportion of the nation’s public and private schools that require daily physical education for all students.

2. Increase the proportion of adolescents who spend at least 50% of school physical education class time being physically active.

3. Increase the proportion of the nation’s public and private schools that provide access to their physical activity spaces and facilities for all persons outside of normal school hours (that is, before and after the school day, on weekends, and during summer and other vacations).

4. Increase the proportion of adolescents that meet current physical activity guidelines for aerobic and for muscle-strengthening activity.

5. Increase the proportion of children and adolescents who meet the guidelines for television viewing and computer use.

6. (Developmental objective) Increase the proportion of trips made by walking.

7. (Developmental objective) Increase the proportion of trips made by bicycle.

8. Increase the proportion of states and school districts that require regularly scheduled elementary school recess (new objective for 2020) (the 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans recommend a minimum of 20 minutes per day recess in addition to PE class while in school).

9. Increase the proportion of physician office visits for chronic health diseases or conditions that include counseling or education related to exercise (new objective for 2020).

American Academy of Pediatrics Guidelines

1. Physicians and health care professionals should participate with schools in implementing and setting goals to develop wellness policies for healthy nutrition, physical activity, and other strategies that promote wellness of students.

2. Advocate for school curricula that emphasize the health benefits of regular physical activity and for recreational programs that promote the use of community and school facilities after hours by children and youth at reasonable costs.

3. Advocate for the reinstatement of compulsory, quality, daily PE classes for K through 12 that are enjoyable and help students develop attitudes and skills for lifelong active lifestyles; maintain school recess, and promote extracurricular physical activity programs before and after school hours.

4. Promote recreational facilities, parks, playgrounds, bicycle and walking paths, sidewalks, and marked crosswalks.

5. Providers should inquire about nutritional intake, plot body mass index (BMI), promote healthy eating and physical activity, and note and discuss the limitation of sedentary activities.

6. Encourage a culture of family physical activity by advocating that parents act as role models, incorporate physical activity in to their own lives, and support their children in age-appropriate sports and recreational activities.

7. Suggest that overweight children initially participate in activities that place less stress on weight-bearing joints, such as swimming, water polo, strength training, and cycling.

Health Benefits of Physical Activity

Health Benefits of Physical Activity

• Prevention of overweight and obesity (reduced body fat) For obese youth, moderate to vigorous physical activity done at a minimum of 3 days per week for a minimum of 30 minutes’ duration each session, reduces adiposity

• Improved cardiovascular health, including increased endurance and improved aerobic capacity

• Reduced risk of metabolic syndrome (type 2 diabetes)

• Improved muscular strength and endurance

• Improved skeletal health including increased bone mineral content and bone mineral density

• Improved general self-concept

• Reduction in depression and anxiety symptoms

• Improved academic performance (measured in better grades, higher standardized test scores, better memory and concentration)

Health Conditions Benefiting From Physical Activity

• Obesity. Inadequate physical activity and energy-dense, nutrient-poor foods are the largest contributors to the staggering rise in childhood obesity rates, not just in the U.S., but internationally. Although reduction of obesity is a national health goal as stated in Healthy People 2010 and 2020, little progress has been made to reduce that epidemic (see Chapter 10 for a discussion on obesity).

Obesity in childhood or adolescence greatly increases the risk that the person will remain obese as an adult. A study in England showed that the propensity to gain weight was related to lower self-esteem in childhood. This weight gain was more likely to occur in children who felt less in control of their lives and who worried (Ternouth et al, 2009). Studies have also demonstrated that a lower body satisfaction in adolescents is related to lower physical activity and more hours of TV watching (Neumark-Sztainer et al, 2004).

Obesity in childhood or adolescence greatly increases the risk that the person will remain obese as an adult. A study in England showed that the propensity to gain weight was related to lower self-esteem in childhood. This weight gain was more likely to occur in children who felt less in control of their lives and who worried (Ternouth et al, 2009). Studies have also demonstrated that a lower body satisfaction in adolescents is related to lower physical activity and more hours of TV watching (Neumark-Sztainer et al, 2004).

• Hypertension. For hypertensive youth, regular aerobic activity helps reduce blood pressure. Studies have shown that the most beneficial type of activity to lower blood pressure is aerobic exercise at a level that improves one’s aerobic fitness for a minimum of 30 minutes, 3 days per week. Resistance training coupled with aerobic exercise has also been shown to be beneficial in terms of maintaining blood pressure within the normal range once the hypertension is resolved (AAP, 2010a; Strong et al, 2005).

• Metabolic syndrome. For individuals with metabolic syndrome, engaging in moderate to vigorous regular physical activity has the positive effects of increasing high-density lipoproteins (HDLs) and reducing triglycerides and insulin levels. Exercise has not been shown to reduce total cholesterol or low-density lipoproteins (LDLs). In the studies reviewed by Strong and colleagues, 40 minutes of moderate to vigorous exercise on 5 days of the week is required to have measurable effects on reducing lipids and insulin level (Strong et al, 2005).

• Reactive airway disease. Children with asthma who do regular aerobic physical activity have been shown to experience improved aerobic and anaerobic fitness. There is no evidence that physical activity improves pulmonary function status (Pianosi and Davis, 2004).

• Special needs children. Children and youth with disabilities require special focus in order to ensure that they have access to the means to be physically active and at levels that offer health benefits. Due to higher levels of physical inactivity, youth with physical disabilities experience poorer cardiovascular health, lower levels of muscular endurance and higher obesity levels than do children without disabilities (Murphy et al, 2008). Benefits of physical activity for children and adolescents with disabilities are physiological and psychological—improved self-esteem, greater independence, and improved social skills. Recommendations for providers to promote physical activities for children having special needs include (Murphy et al, 2008):

Being aware that participation in sports and being physically active is important for children with disabilities

Being aware that participation in sports and being physically active is important for children with disabilities Performing preparticipation examinations to identify the individual’s strengths as well as areas where adaptation is required

Performing preparticipation examinations to identify the individual’s strengths as well as areas where adaptation is required Strategies to Support Physical Activity for Children and Adolescents

Strategies to Support Physical Activity for Children and Adolescents

Motivation and Barriers to Maintaining Physical Activity

A number of factors affect an individual’s motivation to become and/or maintain a physically active lifestyle. Physical activity, like any behavior, operates on a socioecological model. Table 13-1 describes the different levels of influence a clinician can engage in to promote physical activity. The effect of socioeconomics, race/ethnicity, and culture is important to be aware of in order to effectively and equitably address the barriers and resources for physical activity (Brennan Ramirez et al, 2008). A midcourse review of Healthy People 2010 (USDHHS, 2006) describes some local, state, and federal level community health approaches (and the extent of their effectiveness) to decreasing disparities.

TABLE 13-1 Socioecological Model for Effective Promotion of Physical Activity by Providers

CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Can Health Care Providers Influence Lifestyle Behaviors?

Surveys have also reported that physicians doubt their ability to influence lifestyle behaviors, feel they lack formal education needed to counsel effectively, and are not reimbursed for this time-consuming endeavor (Howe et al, 2010; Sesselberg et al, 2010). Although the most recent U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) review concluded that the “evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against behavioral counseling in primary care settings to promote physical activity” (USPSTF, 2002, p 2), others believe that counseling about the health benefits of physical activity is an efficacious use of time and produces results (AAP, 2010b). The MyActivity Pyramid for Kids is a distinctive and fun handout for engaging children and adolescents in efforts to increase their activity levels (see University of Missouri Extension website).

Familiarity with the theories of James Prochaska and Carlo DiClemente about change, motivation, and motivational interviewing will provide practitioners with clinical skills to collaboratively work with patients to support behavioral change. See Chapter 9 for a discussion regarding techniques for motivational interviewing.

Counseling Families about Organized Sports for their Children

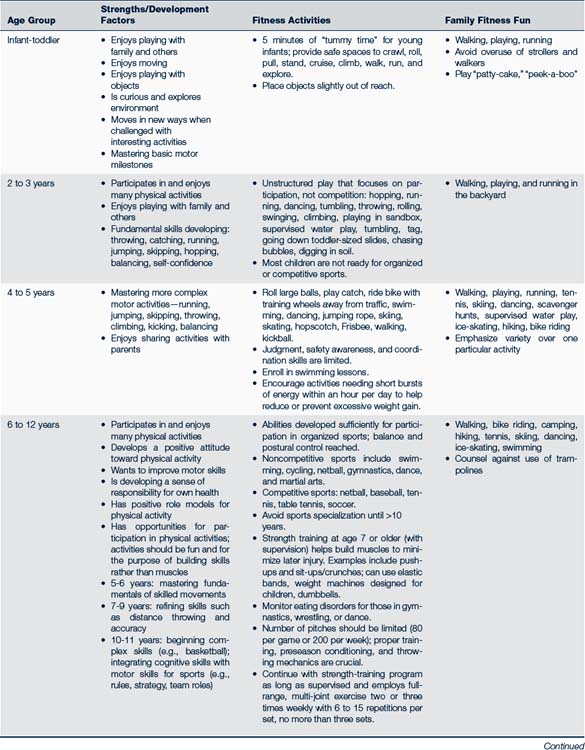

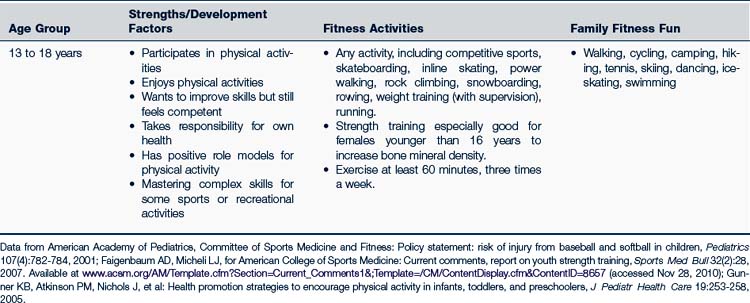

Table 13-2 provides guidance for a developmentally appropriate approach to sports activities. The following are some basic concepts to keep in mind when counseling parents, guardians, and youth about athletic participation (AAP, 2007a):

• Regardless of age, the goals of sports participation should be to have fun, to develop skills, and to form a foundation for lifelong fitness.

The clinician should always be alert for youth athletes who appear to be stressed or pressured by adults (parents, coaches) to achieve a certain level of competition. Explore motivation for participation because there may be pressure to perform in order to get recognized by professional scouts, receive athletic scholarships, or make a varsity team. One study (Savage et al, 2009) showed that perceived encouragement from fathers (but not mothers) for physical activity was a significant factor in mid-adolescence.

The clinician should always be alert for youth athletes who appear to be stressed or pressured by adults (parents, coaches) to achieve a certain level of competition. Explore motivation for participation because there may be pressure to perform in order to get recognized by professional scouts, receive athletic scholarships, or make a varsity team. One study (Savage et al, 2009) showed that perceived encouragement from fathers (but not mothers) for physical activity was a significant factor in mid-adolescence.• For the young child entering sports (preschool through school-age), the goals should be healthy activity, learning basic skills, and rules of the game. The skills of several children of the same age can be widely discrepant.

Up to the age of puberty, any organized athletic activities should complement rather than replace less structured physical activity that focuses on fun and playfulness (e.g., free play, “pick up” games, and school PE).

Up to the age of puberty, any organized athletic activities should complement rather than replace less structured physical activity that focuses on fun and playfulness (e.g., free play, “pick up” games, and school PE). In general, preschool children have limited attention spans and can be distractible. It is advised that structured exercise sessions be short (no longer than 15 to 20 minutes), that there be 30 minutes of free play, and that activities be playful, creative, and allow exploration of movement (AAP, 2007a).

In general, preschool children have limited attention spans and can be distractible. It is advised that structured exercise sessions be short (no longer than 15 to 20 minutes), that there be 30 minutes of free play, and that activities be playful, creative, and allow exploration of movement (AAP, 2007a).• About 7 years old children are generally ready for organized noncontact sports, but involvement should be guided by the individual child’s cognitive and motor development and interest. It is important to keep the focus on participation rather than on winning.

Even with team sports for young children (up through about the age of 10 years), it is advisable to maintain enthusiasm through noncompetitive means (praise, fun experiences, team and leadership building activities). Such things as score-keeping, trophies for performance, awards for “best player,” although well intentioned, may be detrimental to positive self-esteem and one’s future interest in sports for this age group.

Even with team sports for young children (up through about the age of 10 years), it is advisable to maintain enthusiasm through noncompetitive means (praise, fun experiences, team and leadership building activities). Such things as score-keeping, trophies for performance, awards for “best player,” although well intentioned, may be detrimental to positive self-esteem and one’s future interest in sports for this age group. Clinicians are in an excellent position to be sure parents and coaches for the younger child understand the developmental level of this age group.

Clinicians are in an excellent position to be sure parents and coaches for the younger child understand the developmental level of this age group.• About age 10, children become more ready to master complex skills such as rules and strategies for competitive sports. It should always be a goal to keep the focus on skill development, personal improvement, and individual positive strides, rather than on competition, embarrassment, or unnecessary regimentation or stress.

• The child who is an exceptional athlete may still have maturation difficulties in social and psychological areas. Finding a balance in supporting the development of an athletically gifted child can be difficult given the stress this child may face in the competitive arena.

• Parents and coaches should always role model best athletic practices for injury prevention and sportsmanship (e.g., wear bicycle helmets when riding with their children, pre- and postgame handshakes with opposing team members).

• Children with handicaps should be encouraged to participate in sports that best fit their abilities and that are safe.

• Children with academic problems should not be denied participation in sports. Studies have concluded that an increase in PE time at school does not negatively affect academics (CDC, 2010a). Sports can be the best arena for boosting self-esteem for the child who does not experience success in the classroom. Helping the child find a balance between academic work and sports participation is essential.

• Boys and girls can play together, especially in the prepubertal years. Differences in height and weight can make it unsafe for smaller girls to compete in contact sports with boys after puberty.

• Children should not focus on sports specialization until puberty (Brenner, 2007). Prior to that age, it is recommended that children play varied sports, enabling them to maintain their energy and interest for a longer time.

• Sports specialization at a young age and/or overtraining can cause overuse injuries (microtrauma damage to bone, muscle, or tendons that occurs from repetitive overuse without sufficient rest and healing time) and/or “burnout” (symptoms include repeated overuse and other injuries, general fatigue, psychological stress, and decreased athletic performance; participation becomes a chore; and a lack of joy and enthusiasm are expressed) (Metzl, 2003; Smith and Link, 2010).

• Suggestions for preventing overtraining and burnout (Brenner, 2007) include:

Take 1 or 2 days a week off from organized activity, allowing the body to rest (okay for the athlete to do recreational physical activity if desired on the days off).

Take 1 or 2 days a week off from organized activity, allowing the body to rest (okay for the athlete to do recreational physical activity if desired on the days off). Schedule breaks from training every 2 to 3 months (after a season is completed). During this time the athlete can cross-train or participate in other physical activity to stay in shape.

Schedule breaks from training every 2 to 3 months (after a season is completed). During this time the athlete can cross-train or participate in other physical activity to stay in shape.Strength Training

Strength training for young athletes needs to be supervised; there are fewer injuries from strength training than from the sports themselves (notably lower back strains). Box 13-1 lists general guidelines for strength training by the preadolescent.

BOX 13-1 Safe Practices for Strength Training for Youth Athletes

• Children who are ready to play in organized sports (e.g., Little League baseball, soccer) are ready to participate in some form of strength-related activity, even if it consists of only push-ups and sit-ups for young children.

• Strength training should be only one component of a well-rounded fitness program.

• Prior to starting a formal strength training program, the child should ideally have a physical examination, especially if he or she has any known or suspected health condition.

• Athletes and families should be advised of the dangers of using performance-enhancing drugs to increase strength and muscle mass.

• Training should be done under the supervision of a coach or trainer who is familiar with the appropriate training regimens for different age groups and knowledgeable about the equipment and its use.

Training should be progressive—start at zero or low weight with few repetitions; when able to perform sets of 6 to 15 repetitions with ease, gradually increase weight increments by 5% to 10%. Avoid maximal lift weight and powerlifting until Tanner stage 5 has been reached to avoid potential injury to long bones, growth plates, and back (Hatfield, 2010).

Training should be progressive—start at zero or low weight with few repetitions; when able to perform sets of 6 to 15 repetitions with ease, gradually increase weight increments by 5% to 10%. Avoid maximal lift weight and powerlifting until Tanner stage 5 has been reached to avoid potential injury to long bones, growth plates, and back (Hatfield, 2010). Train no more than two or three times a week, on nonconsecutive days to allow for recovery and to produce the greatest gains in strength building.

Train no more than two or three times a week, on nonconsecutive days to allow for recovery and to produce the greatest gains in strength building.• Exercises should be balanced among all muscle groups, including core muscles.

• Ensure adequate fluid intake during training.

• All training sessions should begin and end with a period of warm-up/cool-down exercises that include stretching and dynamic movement, such as a slow jog, jumping, or skipping.

Data from American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Sports Medicine and Fitness: Policy statement: strength training by children and adolescents, Pediatrics 121(4):835-840, 2008a; Faigenbaum AD, Micheli LJ: Preseason conditioning for young athletes, 2000. Available at www.acsm.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Search&;SECTION=Updated_single_page&CONTENTID=8685&TEMPLATE=/CM/ContentDisplay.cfm (accessed Aug 26, 2010); Hatfield D: Strength training for children: a review of research literature. Available at www.protraineronline.com/post/jun1_01/children.cfm (accessed Aug 26, 2010); Young WK, Metzi, JD: Strength training for the young athlete, Pediatr Ann 39(5):293-299, 2010.

Preseason Conditioning and Injury Prevention

A variety of strategies can be used to reduce the incidence and severity of injuries and heat-related illnesses and dehydration (see also Chapter 39). Some of the more typical injury conditions that can be avoided with simple prevention strategies are included in Table 13-3. Readiness can be addressed from two perspectives, developmental readiness and preseason conditioning readiness. Developmental readiness has been previously discussed.

TABLE 13-3 Common Injuries and Prevention Strategies

Use of Helmets for Cycling and Winter Sports

• Try on several sizes and models to find the best fit that:

Positions the brim so that it is parallel to the ground when the head is upright (child should be able to see the brim when looking up). This may require removing or installing inside pads to enable a snug fit, or adjusting sizing ring

Positions the brim so that it is parallel to the ground when the head is upright (child should be able to see the brim when looking up). This may require removing or installing inside pads to enable a snug fit, or adjusting sizing ring Securely fastens the chin strap to the point where the helmet will not shift over the eyes, rock side to side, or come off when the child shakes the head

Securely fastens the chin strap to the point where the helmet will not shift over the eyes, rock side to side, or come off when the child shakes the head• Helmets should carry a USCPSC sticker.

• A helmet should be thrown away if it has been involved in any substantial blow that resulted in marks on the outer surface; do not purchase secondhand helmets.

• Replace helmets every 5 years or sooner, depending on the manufacturer’s recommendations.

• Children are more likely to wear helmets if a parental rule exists about its unconditional use, if parents wear helmets during cycling activities, and if there is a mandatory state helmet law, although these usually only apply to children younger than 16 years.

The efficacy of helmet use for young recreational skiers is controversial. A USCPSC (1999) study estimated that 44% of head injuries (53% for children younger than age 15) and 11 deaths could have been prevented by the use of helmets. The USCPSC study also referred to a Swedish study that found a 50% decrease in head injuries in those using helmets versus those without. Shealy’s (2010) study of head injuries on ski slopes, though, found an increase in injuries when a helmet was used. He conjectured that the use of a helmet was seen as a license to ski faster or take chances (like skiing among trees). The helmeted skiers also suffered more serious head injuries than those unhelmeted. At a speed in the range of 25 to 40 mph, whether one is wearing a helmet or not, a helmet is not viewed by Shealy as providing the protection needed to prevent serious head trauma. Helmets are highly advocated by the National Ski Areas Association and such winter sports programs as Lids on Kids.

Basic Metabolic and Nutritional Needs and Abuses in Athletes

Basic Metabolic and Nutritional Needs and Abuses in Athletes

Growing children and adolescents have higher basal metabolic rates than do adults, and they require sufficient caloric intake to both sustain growth as well as to provide energy and nutrients for sports. Youth athletes are also less energy efficient when physically active than adult athletes, thus, their caloric needs are 20% to 30% greater when doing comparable activities (Baker, 2009). Nutrition recommendations are summarized in Table 13-4.

TABLE 13-4 Nutrition Recommendations for Athletes

Data from American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Nutrition: Guidelines for pediatricians: nutrition and sports, Sports Shorts, issue 6, 2001. Available at www.aap.org/sections/sportsmedicine/PDFs/SportsShorts_06.pdf (accessed Sept 16, 2010).

Calories

Depending on the sport, calorie requirements for active teenagers exceed baseline needs by 1500 to 3000 calories. The recommended diet for the athlete is the same as for all people. The daily energy and micronutrient requirements for athletes at various ages can be found in Chapter 10.

Carbohydrates

In general, carbohydrates will be most effectively converted into the needed energy if they are consumed several hours before the athletic event or practice. Approximately 300 g of carbohydrate-rich food, 2 to 3 hours prior to exercise is recommended. Ingesting carbohydrates just before activities has no effect on performance. Carbohydrate loading has not been studied in children and is generally not recommended. If an athlete is participating in long-endurance events, carbohydrate loading may be appropriate once or twice during an entire season, and only with the guidance of a coach, trainer, or nutritionist with experience in the age group (Baker, 2009). Carbohydrate intake (30 g/hr) during physical activity lasting more than 1 hour improves performance. After competition, carbohydrate intake is again important to improve muscle glycogen resynthesis, which is most rapid in the first few hours after exercise. During the 2 hours after performance, consuming carbohydrates (approximately 75 g) in the first 30 minutes and 100 g every 60 minutes will achieve this resynthesis. This can be in the form of snacks or liquids.

Health Care for Young Athletes

Health Care for Young Athletes

The Preparticipation Physical Examination for Sports

For many youth, the preparticipation physical examination (PPE) is their only health assessment for several years. It may serve as an entry into health care and enable the provider to schedule a follow-up visit to address other health risks and concerns. However, because PPEs are not required for many of the recreational activities in which youth engage, there is a recommendation by a consensus group (consisting of sports medicine practitioners and consultants from the American Academy of Family Physicians [AAFP], the AAP, the American College of Sports Medicine [ACSM], the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine, and the American Osteopathic Academy of Sports Medicine) that a PPE serve as an additional opportunity for a well-child examination for all children. In this way, health and fitness will be promoted and assessed in all children (Editorial Staff, 2010). Included in this examination should be the use of a health questionnaire that targets certain cardiac health issues and the use of standard PPE forms. The PPE monograph contains the recommended questionnaire, PPE, and clearance forms; they are available for downloading from the AAFP. The complete monograph also contains guidelines for clinicians evaluating children with special needs and the female athlete; it is available for purchase (AAFP, AAP, ACSM et al, 2010).

• Evaluating health status, including fitness level

• Detecting injuries, conditions, and illnesses that might limit competition and lead to significant morbidity or mortality and require further evaluation and treatment

• Recommending alternative sports activities, as appropriate, or excluding the person from certain sports

• Identifying lifestyle risk factors and promoting healthy choices

• Documenting an athlete’s age, grade-level eligibility, and emotional maturity level

• Collecting medical data for emergencies

• Recommending ways to improve athletic performance

• Interacting with youth on a variety of health-related issues

Table 13-5 provides recommendations and guidance on safe sports for various medical conditions and can be a useful reference for complex decision-making. In addition, consultation with the appropriate specialist working with the patient’s particular health condition may be needed before giving athletic clearance or recommending any specific modification or adaptation to a fitness regimen.

TABLE 13-5 Medical Conditions and Sports Participation