Chapter 28 Pervasive Developmental Disorders and Childhood Psychosis

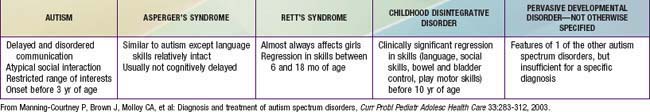

The pervasive developmental disorders (PDD) and childhood schizophrenia can be understood as disturbances of brain development with genetic underpinnings. PDD spectrum includes autistic, Asperger’s, childhood disintegrative, Rett’s, and PDD not otherwise specified (NOS) disorders. Children with these disorders all share the inability to attain expected social, communication, emotional, cognitive, and adaptive abilities (Table 28-1).

28.1 Autistic Disorder

Clinical Manifestations

The core features of autistic disorder (AD) include impairments in 3 symptom domains: social interaction; communication; and developmentally appropriate behavior, interests, or activities (Table 28-2). Stereotypical body movements, a marked need for sameness, and a very narrow range of interests are also common.

Table 28-2 DSM-IV-TR DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR AUTISTIC DISORDER

From American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition, text revision, Washington, DC, 2000, American Psychiatric Association.

Diagnosis

The medical and genetic evaluation of children with PDD must consider a broad range of disorders (Table 28-3). Approximately 20% of children with AD have macrocephaly, but enlarged head size might not be apparent until after the 2nd yr of life. In the absence of dysmorphic features or focal neurologic signs, additional neuroimaging for investigation of macrocephaly is not usually indicated. Multidisciplinary assessment of AD is optimal in facilitating early diagnosis, treatment, and coordinated multiagency collaboration. Evaluations from various other professionals, including a developmental pediatrician or pediatric neurologist, medical geneticist, child and adolescent psychiatrist, speech-language pathologist, occupational or physical therapist, or medical social worker may be indicated.

Table 28-3 MEDICAL AND GENETIC EVALUATION OF CHILDREN WITH PERVASIVE DEVELOPMENTAL DISORDERS

REQUIRED EVALUATIONS

CONSIDER IF RESULTS OF ABOVE EVALUATIONS ARE NORMAL, AND IN CHILDREN WITH COMORBID MENTAL RETARDATION

METABOLIC TESTING TO CONSIDER BASED ON OTHER CLINICAL FEATURES

OTHER TESTING TO CONSIDER BASED ON CLINICAL FEATURES

ELECTROENCEPHALOGRAPHY IF THE FOLLOWING CLINICAL FEATURES ARE NOTED

From Barbaresi WJ, Katusic SK, Voigt R: Autism: a review of the state of the science for pediatric primary care clinicians, Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 160:1169, 2006.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes consideration of the various PDD, mental retardation not associated with PDD (Chapter 33), specific developmental disorders (e.g., of language), early onset psychosis (e.g., schizophrenia), selective mutism, social anxiety (Chapter 23), obsessive-compulsive disorder, stereotypic movement disorder, inhibited-type reactive attachment disorder, and rarely, childhood-onset dementia.

Early Identification

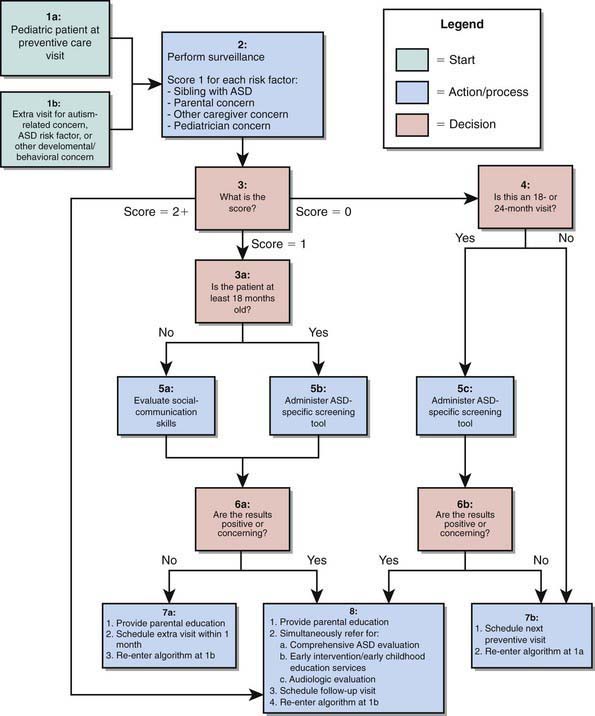

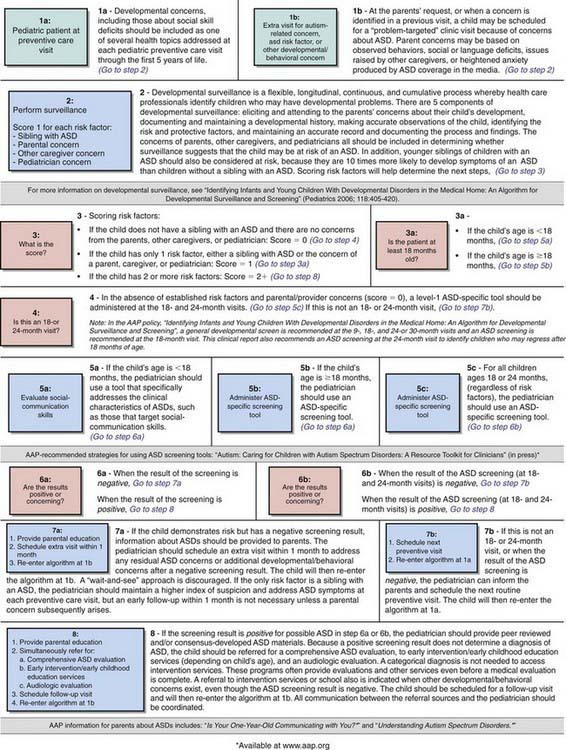

Early identification and intervention of PDD are associated with better outcomes. Several instruments have been developed for screening of PDD in primary care settings including the Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (CHAT), the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (M-CHAT), and the Pervasive Developmental Disorders Screening Test (PDDST) (Chapter 18) (Fig. 28-1). Failures to meet age-expected language or social milestones are important early red flags for PDD and should prompt an immediate evaluation. Early signs include unusual use of language or loss of language skills, nonfunctional rituals, inability to adapt to new settings, lack of imitation, and absence of imaginary play. Deviations in social and emotional development (such as decreased eye contact, failure to orient to name, and lack of joint attention) can often be detected by 1 yr of age. The absence of expected social, communication, and play behavior often precedes the emergence of odd or stereotypical behaviors or the unusual language usage that is seen in AD in the later years.

Treatment

Model early childhood educational programs for children with PDD can be categorized as behavior analytic, developmental, or structured teaching on the basis of the underlying theoretical orientation. Although programs differ in relative emphasis, they share many common goals, including beginning intervention as early as possible; providing intensive intervention (at least 25 hr/wk, 12 mo/yr) in systematically planned educational activities; providing a low student-to-teacher ratio; including parent training; promoting opportunities for interaction with typically developing peers incorporating a high degree of structure through elements such as a predictable routine, visual activity schedules, and clear physical boundaries; implementing strategies to apply learned skills to new environments and situations; and using curricula that address functional spontaneous communication, social skills, functional adaptive skills, reduction of maladaptive behaviors, cognitive skills, and traditional academic skills. Some well-regarded programs that address at least some of these skills include Applied Behavioral Analysis (ABA), Discrete Trial Training (DTT), and Treatment and Education of Autistic and related Communication-handicapped Children (TEACCH). Most educational programs available to young children with PDDs are based in communities in the context of an Individualized Education Program (Chapter 15), and offer an eclectic treatment approach, which may be less effective than standardized protocols.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree