3. Perinatal Transport and Levels of Care*

Mario A. Rojas, Kelly Shirley and Margaret G. Rush

Perinatal transport is the timely and appropriate transfer of high-risk pregnant mothers to health care facilities in which expertise and resources for optimal care are available to improve mortality and morbidity of both the mother and her fetus. If transfer of the mother is not possible because of risk outweighing potential benefit, the objective then shifts to optimizing delivery and birth of the high-risk infant. In the latter situation, it is necessary to have adequately trained professionals to resuscitate and stabilize the infant before his or her transfer to a medical center that has the appropriate expertise and resources.

For perinatal transport to effectively support high-risk mothers and their fetuses, as well as sick newborn infants, each country, state, or region must identify its perinatal resources with respect to physical and human capabilities. This review should include classification of levels of care and expertise, as well as mapping of resources as they exist within specific geographic areas. Classification of perinatal resources according to the different levels of care as recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists in their Guidelines for Perinatal Care4 will direct organization, identification of resources and roles of patient referral and retrieval centers, as well as reveal the natural elevation of care within the geographic area of question (Table 3-1). Historically, regionalization has been recommended as the most effective and cost-efficient use of perinatal resources. 8,11,12,36,45 The implementation of this important strategy is subject to qualitative variance depending on the characteristics of the health care system and resources where it is applied. In countries in which universal health care is the norm, regionalization is more easily implemented, whereas in market-driven health care systems in which de-regionalization is predominant, these provisions for care become more challenging. * Whatever the circumstances, perinatal providers must use innovative strategies to maintain high-quality perinatal transport systems. 19,22

| BPP, Biophysical profile; NCPAP, nasal continuous positive airway pressure; NRP, Neonatal Resuscitation Program; PGE1, prostaglandin E 1; S.T.A.B.L.E., S.T.A.B.L.E. program. | ||||

| Maternal | Neonatal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk-Oriented Prenatal Care | Basic Neonatal Care | Patient Characteristics | Personnel | |

| Level 1 | Medical screening examination/ Patient triage Initial treatment and stabilization Maternal-fetal monitoring/prenatal ultrasound/BPP Non-stress test/stress test 30-minute response time for cesarean section 24-hour clinical laboratory services 24-hour radiology services 24-hour blood bank services | Resuscitation and stabilization (NRP; S.T.A.B.L.E.): Initiation of respiratory support (nasal cannula, oxygen hood, NCPAP, and Neopuff™) Surfactant administration Peripheral IV access/IV fluids Initiation of antibiotics Initiation of PGE 1 when a congenital heart defect is suspected | Uncomplicated maternity and neonatal care Emergency management of unexpected complications Healthy term infants Stable late-preterm infants 35-37 weeks’ gestation | Obstetrician Pediatrician Family physicians Certified nurse midwife Pediatric nurse practitioner 24-hour anesthesia availability |

| Level 2 A | 15-minute response time for cesarean section Complicated cases not requiring intensive care | Level 1 care AND Special care nursery | Complete maternity and neonatal care for uncomplicated and most high-risk patients (infants >32 weeks and >1500 g) | Neonatologist Pediatric neonatal hospitalist 24-hour in-house anesthesia for obstetrics |

| Level 2 B | Capability to provide mechanical ventilation for up to 24 hours or continuous positive airway pressure | Neonatologist | ||

| Level 3 | Provision of comprehensive perinatal health care services for women and neonates of all risk categories Complicated cases requiring intensive care Labor <34 weeks’ gestation | Provision of comprehensive perinatal health care services for women and neonates of all risk categories | Intensive care patients Anticipated need for neonatal surgery | Maternal-fetal specialist Neonatologist Obstetrician |

| Level 3 A | Provide comprehensive care for infants >28 weeks’ gestation and weighing >1000 g Sustained mechanical ventilation | Pediatric surgeon for minor surgical procedures | ||

| Level 3 B | Provide comprehensive care for infants ≤28 weeks’ gestation and weighing <1000 g Sustained mechanical ventilation High-frequency ventilation Inhaled nitric oxide | Full range of pediatric medical and surgical subspecialties | ||

| Level 3 C | Provision of comprehensive perinatal health care services at and above those of subspecialty care facilities Responsibility for regional perinatal health care service organization and coordination | Extracorporeal life support Open heart surgery for congenital cardiac malformations | Pediatric cardiothoracic surgeon | |

Because all hospitals cannot provide all levels of perinatal care, interhospital transport of pregnant women and neonates is an essential component of any regional perinatal effort. Women who are at risk for complications and pose significant risk for adverse outcomes or whose neonates are likely to require intensive care support should be considered candidates for referral during the antepartum period. 25 Similarly, it is accepted medical practice to transfer a neonate to a hospital that can provide the services needed or anticipated to be needed if the birth hospital cannot provide that level of service. †

Once resources are identified and classified, a model for integration of perinatal services may be constructed. Strategic planning at this level will direct the design of the organizational structure of the perinatal transport system, including identification of leadership functions, the different member nurseries/units and their roles, and the definition and process for perinatal elevation of care. This integration will then allow for the creation of a system for continuous data collection and analysis, facilitating a systems approach to problem solving and the implementation of quality improvement strategies within the system. 27

REGIONAL PERINATAL REFERRAL AND TRANSPORT SYSTEM

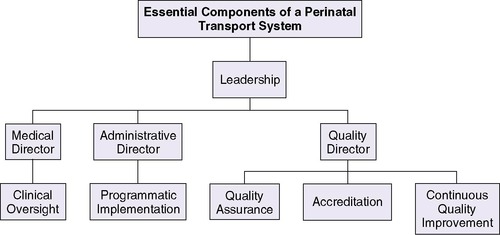

Independent of the health care system with which one identifies (universal versus market driven), the referral system must identify a subspecialty care regional perinatal center, for which the responsibility of coordinating interfacility perinatal transfer lies. Although many different models provide clinical care in transport, the transport system should include the minimal components of (1) leadership (both medical and administrative), (2) communication, and (3) quality assurance (Figure 3-1).

Leadership

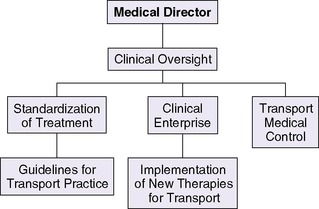

One proposed model is the implementation of a leadership team that comprises a medical director, administrative director, and quality director. This team approach enables collaborative and timely oversight of the transport system with potential for growth and quality improvement. The medical director should be a physician with expertise in transport medicine. The medical director’s role includes overseeing the following37 (Figure 3-2):

|

| FIGURE 3-2 |

• Development, implementation, and monitoring of patient care and transport standards

• Scope of practice of team members

• Team selection

• Training and continuing education

• Support of perinatal partnerships and advocacy

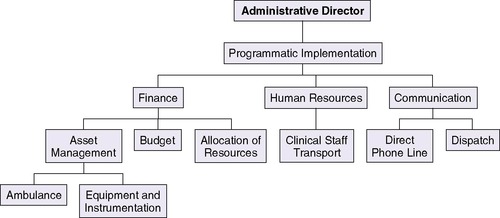

The administrative director working in conjunction with the medical director oversees the budget and day-to-day management of the transport process, including maintenance of equipment. The administrative director should possess clinical transport knowledge paired with strong administrative qualities, because this role includes oversight of finance, human resources, and communication operations (Figure 3-3). 37 The quality director should be a health care provider with a professional background in continuous quality improvement, process analysis, and management. In association with the medical director and administrator, the quality director is responsible for the development and maintenance of a transport database for operational management, quality assurance, and analysis. This administrator should also be able to apply the basic concepts of quality improvement and management to implement novel interventions aimed at improving the perinatal transport system (Figure 3-4). 27

|

| FIGURE 3-3 |

|

| FIGURE 3-4 |

Communication

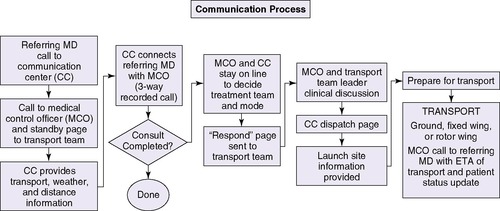

As indicated in Table 3-1, a regional subspecialty perinatal care center should be responsible for coordination of perinatal transport (level 3C). Integral to the regional transport system is the creation of a centralized communication center with a perinatal regional hotline. 20 The communication center is responsible for coordinating maternal and neonatal transports within the different levels of care. Roles within this center include referring physician, dispatcher, bed locator, and transport medical control officer (obstetrician and neonatologist). The inclusion of specialized personnel in the initial communication process may support rendering institutions appropriate treatment strategies while decreasing diagnostic discordance. 46

For purposes of basic communication, a central dedicated telephone line is recommended to provide direct, easy, and immediate access to the regional system. This access should be staffed 24 hours per day, 7 days per week and should be unencumbered. This model also includes the transfer of the referral call to the transport medical control officer, thereby greatly simplifying the process for the referral-consultation. The ability to support communication among the referring physician, the dispatcher, and the medical control officer simultaneously can speed up decision making and the initiation of transport. Once in transport, communication among the transport team, the referring physician, and the medical control officer becomes integral to the care provided (Figure 3-5). Changes in patient status, bed status, equipment needs, and weather need to be communicated in a timely manner. This information may demand a review of the transport plan and is best facilitated through a central communication center. 20,37 The organization of a perinatal regional hotline has been shown to increase significantly both in utero and neonatal transports, allowing for safe, 24-hour, on-call management of perinatal transports and the collection of epidemiologic indicators relative to perinatal transfers. 20

|

| FIGURE 3-5 (Contributed by S. Brodtrick, D. Quinn, and M. Cortez.) |

The rapidly advancing field of telecommunications offers a wide variety of opportunities for transmitting medical information, subject to proper consideration of privacy and confidentiality requirements. This medium permits the use of satellite technology and video-conferencing equipment to conduct a real-time consultation between medical specialists in two geographically different areas. Store-and-forward telemedicine involves acquiring medical data (e.g., medical images, biosignals) and then transmitting this data to a medical specialist for assessment offline. It does not require the presence of both parties at the same time. These technologies may facilitate appropriate referral of patients according to complexity and may decrease incidence of inappropriate transfer or diagnostic discordance, allowing for optimal use of resources. 45,52 Furthermore, these innovative strategies have the potential to overcome de-regionalization of services by creating virtual regional networks for perinatal transport.

Quality

The regional subspecialty perinatal care center, as noted in Table 3-1, is responsible for regional outreach support, education, and continuous quality oversight. Traditionally, quality improvement was assigned to the medical director. However, in light of current health care complexities and regulatory specifications surrounding the quality and safety of patient care, it is recommended that this role be assigned to an individual with the expertise to effectively evaluate programmatic performance at all levels of the organizational structure. This continuous evaluation of the process will facilitate modification of the transport system when potential problems are identified. 27

The leadership team should oversee overall transport performance. The systematic collection and analysis of carefully selected performance indicators such as patient demographics, management and outcome, safety, logistics, equipment malfunction, and cost will drive quality initiatives. A quality review of individual transports, incidence reports, and occurrence debriefs will enhance this process. 37,55 Using a transport validated physiologic score (e.g., the transport risk index of physiologic stability [TRIPS]) to evaluate patient status before, during, and after transport can assist team and transport performance. 34,37

In addition, quality assurance may be implemented through continuing education both internally and externally. Transport programs must create individualized internal training programs that effectively provide current and continuous education to ensure maintenance of appropriate skills for high-quality perinatal transport. A similar program must be adapted to provide educational resources to the referring hospital where training in pre-transport resuscitation and stabilization is imperative. Ensuring competence in these areas has the potential to improve short-term and long-term morbidity of sick infants, offsetting the negative effects of de-regionalization and distance between interhospital transfer facilities. 7,37

High-Risk Maternal Referral

The most effective method to decrease mortality and morbidity during the perinatal and neonatal period is the timely and appropriate referral of mothers with high-risk pregnancies to medical centers in which both the human and technical resources are available to address complications. 14,20In situations in which the risk to the mother outweighs the benefit of her transfer during active labor, the timely dispatch of the neonatal transport team from the regional perinatal center for resuscitation and stabilization of the high-risk neonate may be considered the optimal approach to delivery of care.

Adequate referral of high-risk perinatal patients begins with high-quality antepartum surveillance.48 Indications for referral to a regional center are shown in Box 3-1. Early identification of factors that can affect pregnancy outcome is important in developing appropriate diagnostic and treatment plans. Optimal perinatal care implies having well-trained and up-to-date obstetricians at all levels of care during both the antepartum and intrapartum period. These physicians should be experts in identifying maternal-fetal risk factors and complications through their knowledge, clinical skills, and expertise in prenatal ultrasound and fetal monitoring. 1,17,40,42 In situations in which this level of expertise is not available, medical and nursing personnel should be specifically trained to identify high-risk pregnancies with the objective of pursuing early referral. Consultation and referral decisions for the high-risk mother should be based on the results of a thorough evaluation of each patient and specific guidelines. Communication between the referral center and the regional perinatal center may be facilitated through the use of video-medicine technology. 18

BOX 3-1

A. Prenatal Ultrasound Diagnosis

1. Complex fetal genetic or congenital anomalies

2. Severe intrauterine growth restriction44

3. Hydrops fetalis

4. Severe oligohydramnios and polyhydramnios

5. Fetal airway anomalies

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree