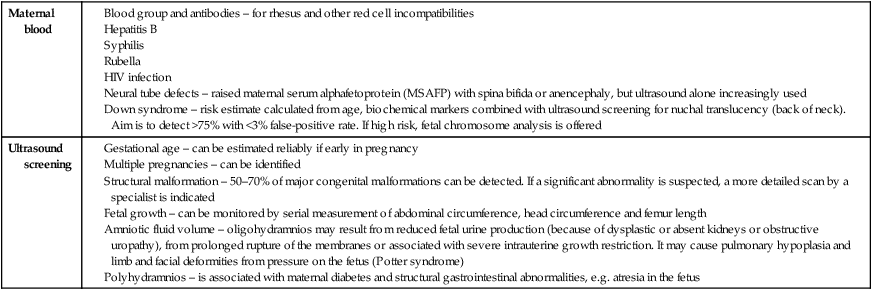

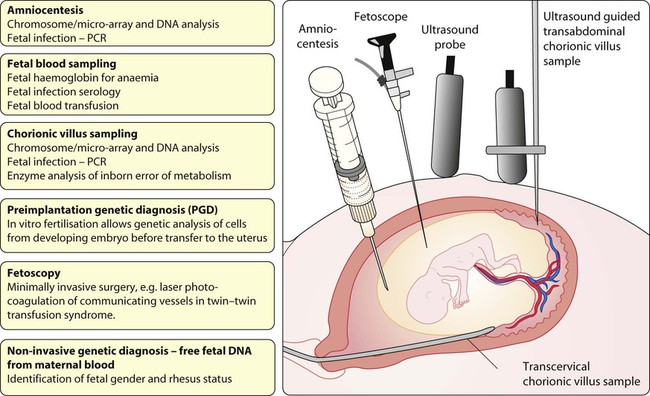

Some definitions used in perinatal medicine are: • Stillbirth – fetus born with no signs of life ≥24 weeks of pregnancy • Perinatal mortality rate – stillbirths + deaths within the first week per 1000 live births and stillbirths • Neonatal mortality rate – deaths of liveborn infants within the first 4 weeks after birth per 1000 live births • Neonate – infant ≤28 days old • Preterm – gestation <37 weeks of pregnancy • Term – 37–41 weeks of pregnancy • Post-term – gestation ≥42 weeks of pregnancy • Low birthweight (LBW) – <2500 g • Very low birthweight (VLBW) – <1500 g • Extremely low birthweight (ELBW) – <1000 g • Small for gestational age – birthweight <10th centile for gestational age • Large for gestational age – birthweight >90th centile for gestational age. • Smoking reduces birthweight, which may be of critical importance if born preterm. On average, the babies of smokers weigh 170 g less than those of non-smokers, but the reduction in birthweight is related to the number of cigarettes smoked per day. Smoking is also associated with an increased risk of miscarriage and stillbirth. The infant has a greater risk of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). • Pre-pregnancy folic acid supplements reduce the risk of neural tube defects in the fetus. Low-dose folic acid supplementation is recommended for all women planning a pregnancy. A higher dose is recommended for women with, or have a close relative with, a previously affected fetus. • Any long-term conditions, such as diabetes and epilepsy, must be reviewed and management changed if necessary. • Certain medications such as retinoids, warfarin and sodium valproate must be avoided because of teratogenic effects. • Alcohol ingestion and drug abuse (opiates, cocaine) may damage the fetus. • Congenital rubella is preventable by maternal immunisation before pregnancy. • Exposure to toxoplasmosis should be minimised by avoiding eating undercooked meat and by wearing gloves when handling cat litter. • Listeria infection can be acquired from eating unpasteurised dairy products, soft ripened cheeses, e.g. brie, camembert and blue veined varieties, patés and ready-to-eat poultry, unless thoroughly re-heated. • Eating liver during pregnancy is best avoided as it contains a high concentration of vitamin A. • the mother is older (if she is >35 years old, the risk of Down syndrome is >1 in 380), although screening is now available for all mothers • there is previous congenital abnormality • there is a family history of an inherited disorder • the parents are identified as carriers of an autosomal recessive disorder, e.g. thalassaemia • a parent carries a chromosomal rearrangement Antenatal diagnosis has become available for an increasing number of disorders. Screening tests performed on maternal blood and ultrasound of the fetus are listed in Box 9.1. The main diagnostic techniques for antenatal diagnosis are maternal serum screening, detailed ultrasound scanning, chorionic villus sampling (at >10 weeks of pregnancy) and amniocentesis (>15 weeks) (Fig. 9.1). In some rare conditions, preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) allows genetic analysis of cells from a developing embryo before transfer to the uterus. The structural malformations and other lesions which can be identified on ultrasound are listed in Box 9.2, with an example in Figure 9.2. Antenatal screening for disorders affecting the mother or fetus allows: • reassurance where disorders are not detected • optimal obstetric management of the mother and fetus • interventions for a limited number of conditions, such as relieving bladder obstruction or draining pleural effusions, to improve perinatal outcome • counselling and neonatal management to be planned in advance • the option of termination of pregnancy to be offered for severe disorders affecting the fetus (see Case History 9.1) or compromising maternal health. The fetus can sometimes be treated by giving medication to the mother. Examples include: • Glucocorticoid therapy before preterm delivery accelerates lung maturity and surfactant production. This has been tested in over 15 randomised trials and markedly reduces the incidence of respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) (relative risk 0.66), of intraventricular haemorrhage (relative risk 0.54) and neonatal mortality (relative risk 0.69) in preterm infants. For optimal effect, a completed course needs to be given at least 24 h before delivery. • Digoxin or flecainide can be given to the mother to treat fetal supraventricular tachycardia. There are a few conditions where therapy can be given to the fetus directly: • Rhesus isoimmunisation. Severely affected fetuses become anaemic and may develop hydrops fetalis, with oedema and ascites. Infants at risk are identified by maternal antibody screening. Regular ultrasound of the fetus is performed to detect fetal anaemia non-invasively using Doppler velocimetry of the fetal middle cerebral artery. Fetal blood transfusion via the umbilical vein may be required regularly from about 20 weeks’ gestation. The incidence of rhesus haemolytic disease has fallen markedly since anti-D immunisation of mothers was introduced but hydrops fetalis is still seen due to other red blood cell antibodies such as Kell. • Perinatal isoimmune thrombocytopenia. This condition is analogous to rhesus isoimmunisation but involves maternal antiplatelet antibodies crossing the placenta. It is rare, affecting about 1 in 5000 births. Intracranial haemorrhage secondary to fetal thrombocytopenia occurs in up to 25%. The problem may be anticipated if there was a previously affected infant, when prenatal intravenous immunoglobulin can be given or repeated intrauterine platelet transfusions performed. • Catheter shunts inserted under ultrasound guidance. This is to drain fetal pleural effusions (pleuro-amniotic shunts), often from a chylothorax (lymphatic fluid) or congenital cystic adenomatous malformation of the lung. One end of a looped catheter lies in the chest, the other end in the amniotic cavity. • Laser therapy to ablate placental anastomoses which lead to the twin–twin transfusion syndrome (TTTS) • Intrauterine shunting for obstruction to urinary outflow as with posterior urethral valves • Dilatation of stenotic heart valves via a transabdominal catheter inserted under ultrasound guidance into the fetal heart. Results appear promising • Endotracheal balloon occlusion for congenital diaphragmatic hernia, as tracheal obstruction in utero may promote lung growth • Surgical correction by hysterotomy. This is when the uterus is opened at 22–24 weeks’ gestation. It has been performed in a few specialist centres for spina bifida but may precipitate preterm delivery and its efficacy remains highly uncertain. Results of fetal surgery to close spina bifida suggest that hydrocephalus may be reduced but does not improve the prognosis of the spinal lesion. The main problems for the infant associated with multiple births are: • Preterm labour. The median gestation for twins is 37 weeks, for triplets 34 weeks and for quads 32 weeks. Preterm delivery is the most important cause of the greater perinatal mortality of multiple births, especially for triplets and higher-order pregnancies. When a higher-order pregnancy is identified, embryo reduction may be offered. • Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR). Fetal growth in one or more fetuses may deteriorate and needs to be monitored regularly. • Congenital abnormalities. These occur twice as frequently as in a singleton, but the risk is increased four-fold in monochorionic twins. • Twin–twin transfusion syndrome (TTTS) in monochorionic twins (shared placenta). May cause extreme preterm delivery, fetal death and discrepancy in growth. • Complicated deliveries, e.g. due to malpresentation of the second twin at vaginal delivery. Finding sufficient intensive care cots for preterm multiple births can be problematic. • Practical – with their care and housework (requires about 200 h/week for triplets in infancy!) • Emotional and physical exhaustion • Increased behavioural problems in the infants and their siblings. While being a multiple birth may provide companionship, affection and stimulation between each other, it may also engender domination, dependency and jealousy. There are local and national support groups for parents of multiple births. Fetal problems associated with maternal diabetes are: • Congenital malformations. Overall, there is a 6% risk of congenital malformations, a three-fold increase compared with the non-diabetic population. The range of anomalies is similar to that for the general population, apart from an increased incidence of cardiac malformations, sacral agenesis (caudal regression syndrome) and hypoplastic left colon, although the latter two conditions are rare. Studies show that good diabetic control periconceptionally reduces the risk of congenital malformations. • Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR). There is a three-fold increase in growth restriction in mothers with long-standing microvascular disease. • Macrosomia (Fig. 9.4). Maternal hyperglycaemia causes fetal hyperglycaemia as glucose crosses the placenta. As insulin does not cross the placenta, the fetus responds with increased secretion of insulin, which promotes growth by increasing both cell number and size. About 25% of such infants have a birthweight greater than 4 kg compared with 8% of non-diabetics. The macrosomia predisposes to cephalopelvic disproportion, birth asphyxia, shoulder dystocia and brachial plexus injury. • Hypoglycaemia. Transient hypoglycaemia is common during the first day of life from fetal hyperinsulinism, but can often be prevented by early feeding. The infant’s blood glucose should be closely monitored during the first 24 h and hypoglycaemia treated • Respiratory distress syndrome (RDS). More common as lung maturation is delayed • Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Hypertrophy of the cardiac septum occurs in some infants. It regresses over several weeks but may cause heart failure from reduced left ventricular function • Polycythaemia (venous haematocrit >0.65). Makes the infant look plethoric. Treatment with partial exchange transfusion to reduce the haematocrit and normalise viscosity may be required.

Perinatal medicine

Pre-pregnancy care

Antenatal diagnosis

Fetal medicine

Fetal surgery

Obstetric conditions affecting the fetus

Pre-eclampsia

Multiple births

Maternal conditions affecting the fetus

Diabetes mellitus

Perinatal medicine