38 Perinatal Disorders

Standards of Care

Standards of Care

• Prenatal screening for Rh(D) incompatibility; human immunodeficiency virus (HIV); hepatitis B; syphilis; chlamydia and gonorrhea

• Neonatal screening for sickle hemoglobinopathies to identify infants who may benefit from antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent sepsis

• Screening for congenital hypothyroidism for all newborns during the first 4 days of life

• Screening for phenylketonuria (PKU) for all newborns before discharge from the nursery. Infants who are tested before 24 hours old should receive a repeat screening test by 2 weeks old.

• Ocular antibiotic prophylaxis of all newborn infants to prevent gonococcal ophthalmia neonatorum

• Routine newborn hearing screening for all infants in the first month of life and an audiologic evaluation for hearing loss in the first 3 months of life

Anatomy and Physiology

Anatomy and Physiology

Intrauterine-to-Extrauterine Transition

The infant’s intrauterine-to-extrauterine transition requires an extraordinary number of biochemical and physiologic changes. In utero, the placenta provides metabolic functions for the fetus. Oxygenated blood from the placenta arrives to the fetus through the umbilical vein. Because of high pulmonary vascular pressure, this blood is shunted from the right to the left side of the fetus’s heart through the foramen ovale or to the systemic circulation through the ductus arteriosus. At birth the umbilical cord is severed. Simultaneously, the infant begins to breathe and the high pulmonary vascular pressure drops, allowing blood flow to the lungs for oxygenation. The foramen ovale and ductus arteriosus are no longer necessary and close after birth. The newborn becomes dependent on gastrointestinal tract function to absorb nutrients, renal function to excrete wastes and maintain chemical balance, liver function to metabolize and excrete toxins, and the functions of the immunologic system to protect against infection. Many newborn problems are related to poor transition to extrauterine life as a result of asphyxia, premature birth, congenital anomalies, or adverse effects of delivery.

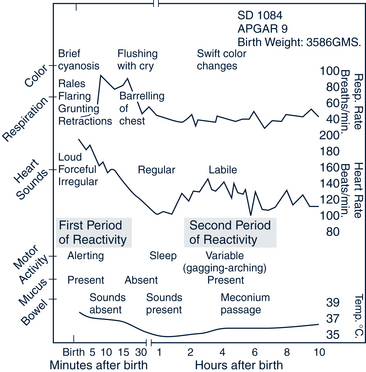

A predictable series of changes or reactivities in vital signs and clinical appearance take place after the delivery of most normal infants (Fig. 38-1). The first period of reactivity includes sympathetic system changes, such as tachycardia, rapid respirations, transient rales, grunting, flaring and retractions, a falling body temperature, hypertonus, and alerting exploratory behavior. Parasympathetic system changes during the first period of reactivity include the initiation of bowel sounds and the production of oral mucus. After an interval of sleep, the infant enters the second period of reactivity. During this time the oral mucus production again becomes evident, the heart rate becomes labile, the infant becomes more responsive to endogenous and exogenous stimuli, and meconium is often passed.

Pathophysiology

Pathophysiology

High-Risk Pregnancy

High-risk pregnancies are defined as those in which factors exist that increase the chances of abortion, fetal death, premature delivery, intrauterine growth retardation, fetal or neonatal disease, congenital malformations, mental retardation, and other handicaps. Identification of a high-risk pregnancy is the first step toward prevention of neonatal problems (Box 38-1). Comprehensive and frequent prenatal visits for women with high-risk pregnancies are aimed at preventing complications in the newborn.

BOX 38-1 Factors Associated With High-Risk Pregnancies

Demographic Social Factors

Maternal age less than 20 years or greater than 35 years

Developmentally delayed mother or low educational status

Illicit drug, alcohol, cigarette use

Poverty, unemployed, homelessness

Emotional or physical stress including depression and other mental health problems

Poor access to or use of prenatal care, underinsured or uninsured

Medical History

Hypertension, maternal hypercoagulable state, sickle cell disease, congenital heart disease

Autoimmune disease including rheumatologic illness (SLE)

Sexually transmitted infections (colonization: herpes simplex, GBS, syphilis, HIV)

Prior Pregnancy

Intrauterine fetal demise or neonatal death

Prematurity or low-birthweight infant

Intrauterine growth retardation

Blood group sensitization, neonatal jaundice

Present Pregnancy

Uterine bleeding (abruptio placentae, placenta previa)

Inception by reproductive technology

Poor weight gain or abnormal fetal growth

Multiple gestation, parity more than 5

Premature rupture of membranes

Polyhydramnios or oligohydramnios

Labor and Delivery

Premature labor (<37 weeks) or prolonged labor

Postdates (>42 weeks) or prolonged gestation

Immature L/S ratio: absent phosphatidylglycerol

Neonate

Birthweight less than 2500 g or greater than 4000 g

Birth before 37 or after 42 weeks of gestation

Small or large for gestational age

Adapted from Stoll BJ: High-risk pregnancies. In Kliegman RM, Behrman RE, Jenson HB et al, editors: Nelson textbook of pediatrics, ed 18, Philadelphia, 2007, Saunders, p 684.

Acquired Health Problems

In utero exposure to poor nutrition, alcohol, drugs, viruses or bacteria, and maternal conditions, such as hypertension and diabetes, can result in prematurity and abnormalities at birth. The risk of neonatal problems increases with maternal age younger than 20 years and older than 35 years (see Box 38-1).

Assessment of the Neonate

Assessment of the Neonate

History

• Past maternal health history

Medications used during pregnancy including prescription, over-the-counter, and natural health products

Medications used during pregnancy including prescription, over-the-counter, and natural health products Infections (including group B streptococcus [GBS] status and results of other screening tests) and illnesses during pregnancy

Infections (including group B streptococcus [GBS] status and results of other screening tests) and illnesses during pregnancy Duration of labor, duration of ruptured membranes, analgesia, anesthesia, presentation and route of delivery, use of forceps

Duration of labor, duration of ruptured membranes, analgesia, anesthesia, presentation and route of delivery, use of forcepsPhysical Examination

Immediately After Birth

Apgar Score

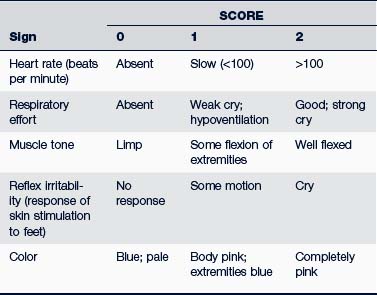

Immediate evaluation of the newborn infant at 1 and 5 minutes old can be a valuable routine procedure. An Apgar score is assigned to the baby based on the criteria in Table 38-1.

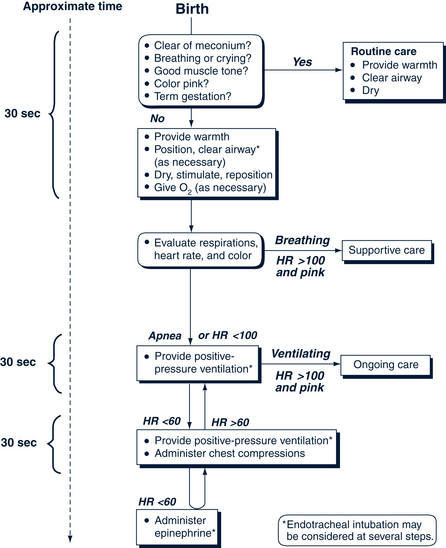

The 5-minute Apgar score is an indication of how well the resuscitation efforts have succeeded. Caution must be exercised when using the Apgar score to predict long-term outcomes of mortality and developmental delay. Only when combined with other factors, such as fetal status, umbilical cord or scalp blood pH, evidence of organ injury, or seizures, can the Apgar score be useful in determining long-term outcome (AAP, 2006). In actual practice, the decision to resuscitate an infant typically is based on a quick assessment of the heart rate, color, and respiratory rate rather than the full 1-minute Apgar score (Fig. 38-2).

FIGURE 38-2 Resuscitation in the delivery room.

(From Niermeyer S, Kattwinkel J, Van Reempts P: International guidelines for neonatal resuscitation: an excerpt from the Guidelines 2000 for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care: International Consensus on Science, Pediatrics 106[3]:29, 2000.)

Gestational Age

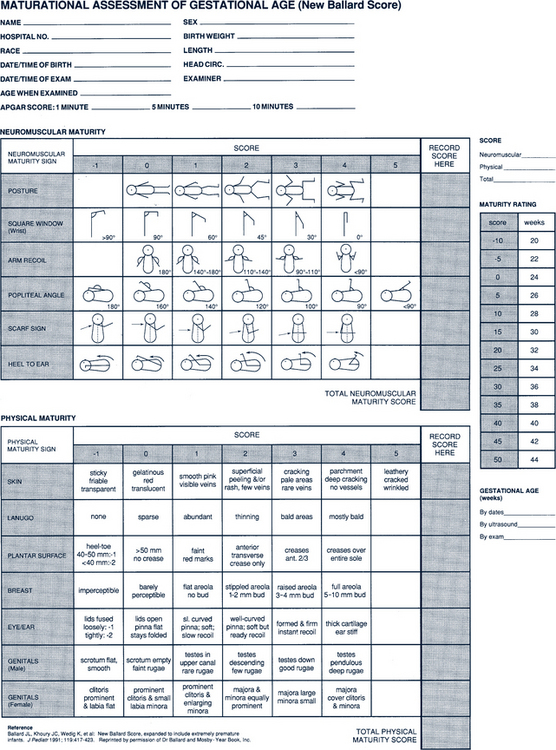

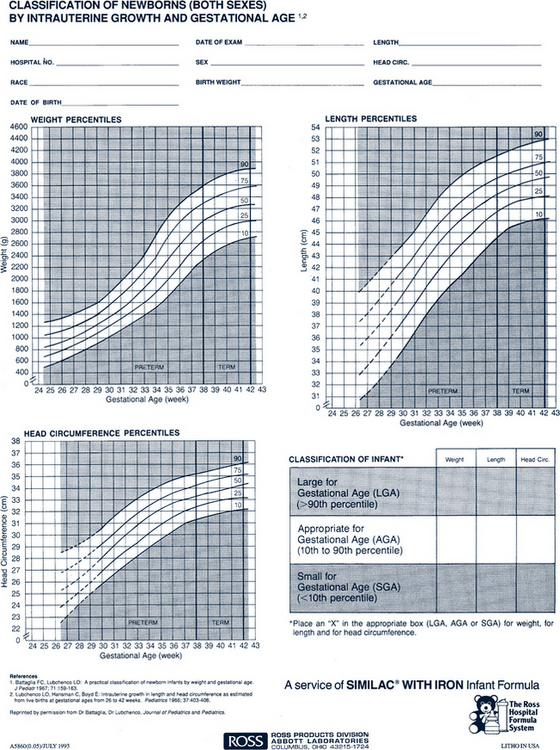

Maturational assessment of an infant’s gestational age is based on the physical examination (Fig. 38-3). The assessment is done promptly after birth to confirm maternal estimated dates, and interpreted with information on the mother’s menstrual history, obstetric milestones achieved during pregnancy, and prenatal ultrasonograms. An infant’s length, weight, and fronto-occipital head circumference are measured and plotted on growth curves based on gestational age (Fig. 38-4). Infants whose weights fall above the 90th percentile for age are classified as large for gestational age (LGA); those whose measurements fall below the 10th percentile for age are classified as small for gestational age (SGA). Those whose measurements fall between the 10th and 90th percentiles are classified as appropriate for gestational age (AGA).

FIGURE 38-3 Classification of newborns by intrauterine growth and gestational age.

(From Ballard JL, Khoury JC, Wedig K et al: New Ballard score, expanded to include extremely premature infants, J Pediatr 119:417-423, 1991.)

FIGURE 38-4 Newborn maturity rating and classification.

(From Ross Hospital Formula System, Ross Products Division, Abbott Laboratories, Columbus, OH; adapted from Battaglia FC, Lubchenco LO: A practical classification of newborn infants by weight and gestational age, J Pediatr 71:159-163, 1967; Lubchenco LO, Hansman C, Boyd E: Intrauterine growth in length and head circumference as estimated from live births at gestational ages from 26 to 42 weeks, Pediatrics 37:403-408, 1966.)

Temperature

Body surface area of the newborn infant relative to its weight is approximately three times that of the adult. Estimated rate of heat loss in the newborn is four times that of an adult (Stoll, 2007a). Body temperature falls precipitously in a cool environment unless adequate precautions are taken. Towel dry the infant after birth to prevent evaporative heat loss, use radiant warmer, and wrap infant in warm blankets and cover the head to reduce heat loss when the baby will be held by parents.

After Stabilization

After a quick initial assessment in the delivery room to evaluate for obvious problems, a more complete physical examination is done (Table 38-2). When performing the physical examination, the infant’s gestational age, age in hours, and stage of transition must be considered.

TABLE 38-2 Physical Examination Findings

| System | Findings |

|---|---|

| Vital signs and measurement | Check vital signs frequently in the first hours after birth, then every 6-8 hr when stable. Evaluate ability to maintain temperature (97.7° to 99.3 ° F [36.5° to 37.4° C]) in open crib after transition to extrauterine environment. Failure to maintain temperature requires evaluation for other problems, particularly sepsis. Respirations should remain between 30 and 60 breaths/min. Heart rate should remain between 100 and 160 bpm. Significant molding of the head requires repeated measurements to verify size. Daily weight losses of up to 10% in the first 2-3 days of life are not abnormal because normal infants excrete a large amount of water in the first days of life. Weight loss of greater than 10% is unexpected and is often due to poor intake or excessive losses. |

| Skin | Lanugo and vernix. Lanugo is fine dark hair, prominent over the trunk and shoulders. It is seen in infants born prematurely, becoming less prominent as the gestation approaches term. Thick, greasy, white vernix is more common on prematurely born infants’ skin. Dry and cracked skin. This is normal over the first several days of life. If associated with thin subcutaneous fat (parchment-like), it is suggestive of a postmature infant, fetal growth retardation, or both. Cyanosis. Acrocyanosis, bluish changes in the color of the hands and feet, and generalized mottling of the skin are frequently noted in the first several days of life when an infant loses body heat. Central cyanosis beyond the first few moments of life is abnormal and can represent a significant problem with oxygenation. Pallor. Many perinatal events can result in pallor, indicating a significant disruption of the infant’s circulatory system. Specific causes include anemia, sepsis, cold stress, hypoglycemia, and seizures. Plethora. An excessively reddish discoloration to the skin can be caused by polycythemia or hyperthermia. Infants born to diabetic mothers can be plethoric. Meconium staining. Antenatal stress can cause the first stool to pass in utero. If this greenish black meconium remains in the amniotic fluid for a prolonged period, staining of the infant’s skin and fingernails results. Jaundice. See the discussion of jaundice in the text under Hematologic Conditions. |

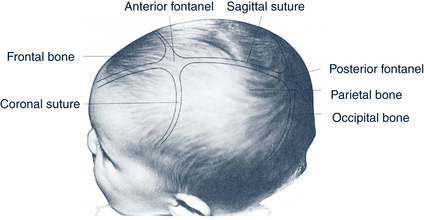

| Head | Sutures and molding. Vaginally delivered infants demonstrate some degree of molding, usually elongation of the anteroposterior diameter of the skull; if delivered by cesarean method, there are minimal alterations to the shape of the head. Fontanelles. The anterior fontanelle is usually about 2-3 cm in diameter; the posterior fontanelle is about 1 cm in diameter. Both are usually slightly depressed (see Fig. 38-5). |

| Face | Symmetric structures of the face should be apparent, although unilateral facial edema as a result of delivery conditions can occur normally. Overall view of the face may reveal maxillary or mandibular hypoplasia, distortion, or hemifacial hypoplasia. |

| Eyes | Too small or large, too widely spaced, or abnormal upward or downward slanting of palpebral fissures should alert the practitioner to potential congenital problems. Uncoordinated eye movements. Intermittent uncoordinated eye movements (disconjugate gaze) during the first weeks after birth are common, improving by 2-4 months old and resolving by 6 months old. Fixed disconjugate gaze is abnormal, even in the neonate. Conjunctivae. Reddening in the first 24-48 hours of life caused by chemical irritation of the eyes from silver nitrate drops or erythromycin ointment is normal. Purulent discharge in the first days or weeks of life can be associated with gonococcus, chlamydia, or herpes. Conjunctival hemorrhages secondary to delivery resolve spontaneously over the first weeks of life. Sclerae. Yellowing is associated with hyperbilirubinemia. Small hemorrhages secondary to delivery resolve spontaneously over the first weeks of life. Thinning of the sclera, common in African-Americans, is manifested by dark blue or black patches. Blue sclerae are associated with osteogenesis imperfecta. Red reflex. Shining an ophthalmoscope’s white light through the pupil reveals the “red reflex,” a disk ranging from pearly gray to orange. Absence of a red reflex may indicate the presence of lens opacities secondary to cataracts, congenital infection (rubella), or calcium metabolism abnormality. A white reflex can indicate retinoblastoma. Absence of the expected red reflex indicates the need for an immediate ophthalmologic evaluation. |

| Ears | Identify normalcy in the size, rotation, shape, position, and patency of the external auditory canal. Presence of low-set ears should prompt careful examination for other dysmorphic features. Abnormalities in shape require thorough physical examination, especially of the genitourinary system. Assessment of hearing is done by noting a startle response to a loud noise, avoiding any tactile sensations, such as a wind current on the face as a result of clapping near the ear. Auditory brain response testing should be ordered for any infant in whom a question of hearing exists. Screening for universal detection of infants with hearing loss is recommended and is especially important for high-risk infants (e.g., family history, in utero infection, craniofacial anomalies, syndromes associated with hearing loss). Preauricular skin tags or significant pits should be noted (can be a genetic red flag). See text section on skin dimpling. |

| Nose | Patency of the nasal passages can be tested by closing the mouth and one nostril at a time or by passing a small catheter into the nasopharynx to see if the passage is clear. Nasal flaring is a sign of respiratory distress that can be caused by any number of abnormalities, including mechanical obstruction, parenchymal lung disease, or acidosis. |

| Mouth | Size and symmetry of the lips • Thin lips with a smooth philtrum (the area between lips and nose) are associated with fetal alcohol syndrome. • Asymmetric movements while crying can be due to nerve palsies or absence of perioral muscles. Excessive salivation can be related to reflux of gastric contents or esophageal atresia. Epstein pearls are small white epithelial inclusion cysts on the palate and gums. An excessively large tongue can be associated with genetic or metabolic abnormalities, such as hypothyroidism or Down syndrome. Natal teeth are sometimes seen at birth (approximately 1 in 3000 live births). If they are extremely loose, aspiration is a concern. Consultation with a pediatric dentist is indicated. |

| Neck | Short neck indicates the possibility of Klippel-Feil syndrome or other vertebral problems. Webbing. Redundant skin is seen in trisomy 21, Turner syndrome, and Noonan syndrome. Masses Torticollis. Asymmetric shortening of the sternocleidomastoid muscle results in preferential turning of the head to one side, not to be confused with irritability of neck movement associated with meningitis or subarachnoid hemorrhage. Hematoma of the sternocleidomastoid muscle can result in the development of torticollis and requires early management. |

| Thorax | Shape, symmetry. Rounded appearance measuring about 2 cm less than the fronto-occipital head circumference (approximately 33 cm): • Minimization of rounding occurs with RDS, atelectasis, and other diseases of decreased expansion of the chest. • Accentuation is seen in meconium aspiration. Wide-spaced nipples and a shieldlike appearance are characteristic of Turner syndrome. |

| Lung | General. Coughing, retractions, and an intermittently increased respiratory rate occur immediately after birth, resolving by about 12 hours of life to smooth and unlabored respirations at a rate of 30 to 60 breaths/min. Respiratory distress. Tachypnea, apnea (pauses in respiration >15 seconds), grunting (an infant’s attempt to increase functional residual capacity, thereby improving gas exchange), interclavicular, subclavicular, or supraclavicular retractions, nasal flaring, and central cyanosis all indicate distress. Auscultation • Rales or crackles are commonly heard immediately after birth as lung fluid is resorbed. Beyond the immediate postpartum period, rales can indicate pneumonia, delayed resorption of lung fluid, meconium aspiration, or pulmonary edema. • Unilateral absence of breath sounds occurs in pneumothorax, atelectasis, and pleural effusion. • Bowel sounds over the chest, especially with a scaphoid abdomen and significant respiratory distress, indicate a diaphragmatic hernia with displacement of abdominal contents into the chest. |

| Heart | Inspection. Observe neonate for adequacy of perfusion. Respiratory distress is common with cardiac abnormalities. Edema as a result of cardiac failure is rarely seen in the newborn. Palpation • Point of maximal impulse is displaced from the fourth left intercostal space with pneumothorax, situs inversus, or dextrocardia. • Thrills or heaves are associated with murmurs and cardiac abnormalities. Murmurs. Common in the newborn period, many murmurs disappear after a few hours or a few days. Significant murmurs should be investigated. Pulses. Brachial or radial pulses are compared with femoral or dorsalis pedis pulses for symmetry of impulse and strength in pulse. Delay or relative weakness of lower extremity pulses occurs in coarctation of the aorta. Blood pressure. By Doppler device using a 2.5-4 cm wide and 5-9 cm long cuff, compare with normals for age and gestation. Systolic blood pressures greater than 96 mm Hg are considered significant hypertension in the newborn, and systolic blood pressures exceeding 106 mm Hg are considered severe hypertension. |

| Abdomen | General • Normal abdomen is slightly protuberant, is soft, moves smoothly with respirations, and has fine bowel sounds scattered throughout. Absent bowel sounds can indicate ileus. • The liver is usually palpated 1-2 cm below the right costal margin; the spleen tip is sometimes felt at the left costal margin; kidneys, deep within lateral aspects of the abdomen measuring 3-4 cm in size, may be palpated. • Pain is indicated by crying, grimacing, or forceful resistance with palpation. Umbilical vessels. The normal cord contains two arteries and a single vein. Absence of the second artery can be associated with congenital abnormalities. Vomiting and abdominal distention. Regurgitation of large volumes of feeding is not expected. • Bilious vomiting is always abnormal and usually a sign of obstruction. • Abdominal distention with enlargement of any of the organs of the abdomen or failure to pass stool is abnormal. • Meconium ileus with failure to pass stool in the first 24-48 hours of life is associated with cystic fibrosis. |

| Genitalia | Male • The penis should have the urethral opening at the tip of the phallus with completely developed foreskin. Chordee means that the distal end of the penis is bent. • Testes not located in the scrotal sac or inguinal canal but retrievable to the scrotum are normal. Testes not located in or relocated in the scrotal sac from the canal are considered to be undescended. • Hydrocele is identified by transilluminating fluid collection around the testis and is regarded as normal unless it is associated with inguinal hernia or it lasts more than 12 months. • Inguinal hernia with displacement of intestines into the scrotal sac is frequently nontransilluminating and is associated with bowel sounds. Inguinal hernias are sometimes apparent and reduced at other times. A surgical consultation is indicated. Female • Labia majora are large and completely surround the labia minora. • Labia and vagina should be open, often with a white discharge. Anus and rectum. Patency of the rectum and placement of the anus should be noted. A small amount of blood streaking in the diaper, especially with a small anal fissure, is common. |

| Extremities, back, hip | Molding. Intrauterine constraint and resultant molding cause mild curvatures of the forefeet (metatarsus adductus vs. varus [in-toeing or out-toeing]) or the tibia (genu varum [bowleg], genu valgum [knock-knee]), or both. See Chapter 37 for more information. Contractures of the joints and molding of the bones occur if amniotic fluid was decreased and is abnormal. Fractures • Skull fractures can occur as a result of extensive molding of a large head. • Clavicle. Femora and humeri can fracture with difficult deliveries and use of instrumentation. Hips. See Chapter 37 for information about eliciting Ortolani and Barlow signs. Both are indicators of dislocated or dislocatable hips. |

| Neurologic examination | Muscle tone. Observe tone, movement, and symmetry of the extremities while the infant is awake. Reflexes. Elicit the following: Cranial nerves. Cranial nerve (CN) I (olfactory) is rarely tested. Vision (CN II) is tested by an infant’s response to a bright light. CNs III, IV, and VI are tested by noting an infant’s ability to gaze in all directions, although intermittent disconjugate gaze is normal through 6 months old. Adequate sucking and swallowing confirm presence of CNs V, IX, X, and XII. Symmetric movement of the face with crying confirms presence of CN VII. Hearing (CN VIII) is assessed by startle to loud noise. |

bpm, Beats per minute; CNS, central nervous system; LGA, large for gestational age; RDS, respiratory distress syndrome.

Diagnostic Studies

All states in the U.S. require screening of infants for a variety of congenital abnormalities, although the screening tests performed vary from state to state (see Chapter 40). Infants should be screened before they are discharged and before the seventh day of life; if initial screen was before 24 hours of life, rescreening should be done by 14 days old. Although most infants require no special screening tests, some are at risk for predictable complications in the newborn period. Infants born to mothers with poorly controlled diabetes and LGA or SGA infants are at higher risk for hypoglycemia and usually require serum glucose level screening. Similarly, infants demonstrating Coombs test positivity because of maternal-child blood incompatibility are screened for evidence of hemolysis. Some nurseries screen both mothers and infants for syphilis; mothers should be screened for HIV and hepatitis B unless done prenatally. Universal hearing screening is recommended by 1 month of age (see Chapter 29), and special attention is paid to any newborn at higher risk for hearing loss as a result of low birthweight, rubella or other infection, malformation, trauma, asphyxia, prematurity, intensive care unit stay, or antibiotic use.

Management Strategies

Management Strategies

Establishing Feeding

Regardless of the route of feeding the family has chosen, the provider must ensure that the infant and parents have well-established feeding patterns before discharge. Follow-up care is scheduled in 2 or 3 days to ensure adequate ongoing nutrition. See Chapters 10 and 11 for more detailed information on breastfeeding and formulas.

Anticipatory Guidance Before Discharge

Physical Care

Circumcision

Care of the uncircumcised baby includes gentle cleaning around the genital area. The skin normally adheres to the penis and is not retractable at birth, but loosens as the baby grows. The parents are counseled not to force the foreskin back. If the baby is circumcised, the penis should be cleansed daily with cotton balls dipped in tap water followed by the application of a small amount of petroleum jelly to the tip of the penis with each diaper change to prevent discharge from the penis sticking to the diaper. The petroleum jelly is needed only for the first 2 to 3 days after the circumcision.

Sleep Position

• Placing infant in a supine position (side-lying is not recommended)

• Avoiding soft surfaces and gas-trapping objects in an infant’s sleeping environment

• Advising that co-sleeping can be hazardous, but sleeping in the same room as the caregiver for the first 6 months of life may be beneficial

• “Tummy time” during the awake period—recommended for developmental reasons and to help prevent flat spots on the occiput

Injury Prevention

The appropriate use and installation of a crash-tested safety seat are essential. The best child safety seat is the one that fits the child properly, is easy to use, and fits in the parent’s vehicle correctly. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration rated scores of infant child restraint systems for ease of parental use. Correct installation of the infant safety seat can be checked at a child safety seat inspection station (often located in fire stations) or by a certified child passenger safety technician. Most hospitals have a certified person on-site who can assist parents when the infant leaves the hospital, or one can be located by searching the Internet. At the first visit it is ideal to have a trained staff member check for appropriate positioning and belt use. It is disconcerting that 80% of car seats are used inappropriately (AAP, 2002) (see Chapter 39).

The house should be childproofed before the infant is taken home. Falls and burns are the most common injuries to neonates. Parents should be counseled to avoid shaking their baby for any reason (refer to Chapters 9 and 39 for more information).

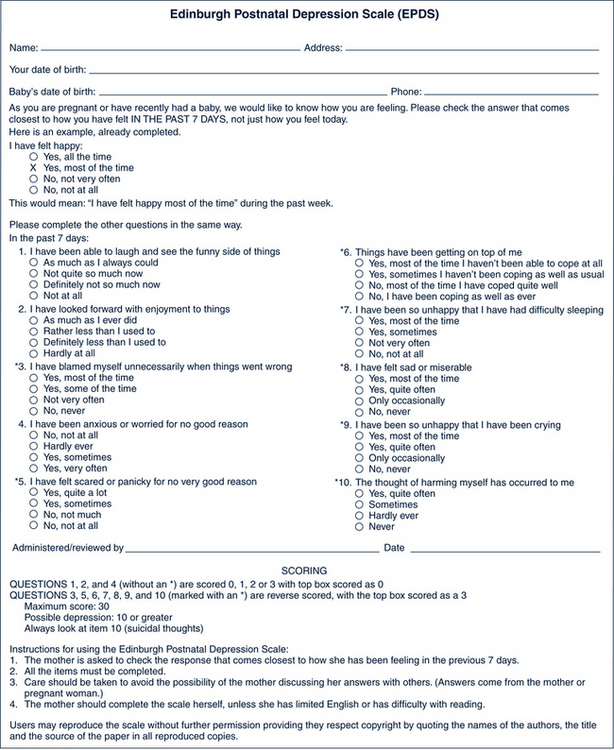

Parenting

The parenting role is stressful, even if all goes well. Fatigue and maternal depression resulting from hormonal shifts are common. Encourage parents to identify and make use of supportive people, arrange time for rest and time alone, and keep their expectations reasonable. When a mother seems to be having significant difficulty in adjusting to her new infant, it is imperative that the provider also keep in mind the possibility of severe postpartum depression and be ready to intervene on the behalf of the infant, the mother, and the family. The 10-question Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) is an easy-to-administer tool that is a valuable and efficient way of identifying mothers at risk for perinatal depression (Fig. 38-6). Women with postpartum depression need not feel alone; intervention, with possible referral for mothers whose score indicates a depressive illness, should be individualized.

FIGURE 38-6 Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS).

(From Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R: Detection of postnatal depression: development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale, Br J Psychiatry 150:782-786, 1987; Wisner KL, Parry BL, Piontek CM: Postpartum depression, N Engl J Med 347[3]:194-199, 2002.)

Early Discharge and Follow-up

Newborns are often discharged after a relatively short period of hospital observation. Although “early discharge” is a common practice, infants can experience difficulty with breastfeeding, poor weight gain, jaundice, and dehydration (Madden et al, 2004). Guidelines for early discharge of normal, healthy newborns are listed in Box 38-2. Plans for follow-up care within 48 to 72 hours and plans for ongoing health maintenance should be confirmed before discharge (Box 38-3). Even newborns who are hospitalized longer may need follow-up care within the first few days of life. All parents leaving the hospital with a newborn should have a confirmed time and place for follow-up, in addition to contacts in case of an emergency or questions.

BOX 38-2 Guidelines for Early Discharge of Normal, Healthy Newborns

• No ongoing medical issues that require continued hospitalization

• Term (37 to 41 completed weeks) baby

• Stable vital signs for at least 12 hours before discharge:

• Regular passage of urine and at least one stool

• Two successful feedings have been accomplished

• No excessive bleeding at circumcision site

• The clinical significance of jaundice has been determined and appropriate follow-up plans made

• Evaluation and monitoring for sepsis based on maternal risk factors have been accomplished

• Infant laboratory data, including maternal syphilis, hepatitis B, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and infant blood type and Coombs testing (as indicated) completed

• Appropriately timed neonatal metabolic and hearing screenings completed

• Initial hepatitis B administered

• Social support and continuing health care identified

• Social situation adequate: screen for drug abuse, previous child abuse, mental illness, lack of social support, lack of permanent home, history of domestic violence, communicable diseases in the household, teenage mother, inadequate transportation or communication abilities

• Appropriate medical home identified with early follow-up care achievable preferably within 48 hours of discharge but no later than 72 hours in most cases

• Mother knowledgeable in the care of the infant, including the following:

Data from American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP): Policy statement-hospital stay for healthy term newborns, Pediatrics 125:405-409, 2010.

BOX 38-3 Guidelines for 48- to 72-Hour Follow-up Visit of the Normal, Healthy Newborn

• Review delivery and discharge summary for any identified follow-up needs (e.g., hearing screening, specialty referrals)

• Assess the infant’s general health, weight, hydration, and jaundice; identify any new problems; review feeding, stooling, and urination

• Reinforce maternal and family education

• Review outstanding laboratory data

• Perform neonatal screen or other tests (such as bilirubin), if indicated

• Develop plan for health care maintenance, including emergency care, preventive care, immunizations, and periodic screenings

• Evaluate mother for post-partum depression

• Refer to Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program eligibility screening as appropriate.

Premature Infants and Newborns With Special Needs

Premature infants have special needs that must be addressed before discharge (Box 38-4). Newborns with special needs (e.g., anomalies, disease states, social situations) require early assessment, intervention, and referral before discharge to ensure that support, education, and follow-up are in place.

BOX 38-4 Guidelines for Discharge and Follow-up of the High-Risk Neonate

Discharge Planning

• Demonstrate adequate weight gain, temperature control in open crib, adequate feeding without cardiorespiratory compromise, and mature and stable cardiorespiratory function.

• Ensure adequacy of immunizations based on infant’s chronologic age and appropriate metabolic screenings.

• Screen for anemia and nutritional risks; begin therapy, if indicated.

• Conduct funduscopic evaluation if necessary.

• Ensure appropriate hearing screen has been completed.

• Identify all active medical or social problems through a review of the medical record and physical examination of infant; ensure home readiness has been evaluated, especially for the technologically dependent child.

• Complete car seat evaluation.

• Review with family member medications, feeding schedules, well-child care, signs of illness, safety instruction, and appropriate response and follow-up for infants with active medical conditions.

• Identify family and community resources if infant is to be discharged on home oxygen therapy.

• Ensure adequate training of appropriate family members in cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and, if applicable, home apnea monitor or other equipment use.

• Consider need for visiting nurse, social service, respite care, support groups, early intervention services, or referral to the Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program.

• Ensure that follow-up care is arranged to include a primary care provider and surgical or other subspecialty providers, if indicated.

Follow-up Planning

• Schedule follow-up hearing screen (if necessary) for infants with:

• Ensure that by about 4 to 6 weeks of chronologic age a dilated binocular indirect ophthalmoscopic examination has occurred for neonates with:

A birthweight between 1500 and 2000 g or gestational age of more than 32 weeks with an unstable clinical course including cardiorespiratory support, especially if infant is thought to be at high risk for retinopathy of prematurity (see Chapter 28)

A birthweight between 1500 and 2000 g or gestational age of more than 32 weeks with an unstable clinical course including cardiorespiratory support, especially if infant is thought to be at high risk for retinopathy of prematurity (see Chapter 28)• Additional examinations may be recommended based on the results of this first evaluation.

• Follow-up visits every 1 to 2 weeks, especially if infant is on oxygen therapy

• Growth and development should be of prime interest at each routine outpatient visit with referral for formal developmental assessment if any concerns are identified.

Data from American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP): Hospital discharge of the high-risk neonate, Pediatrics 122:1119-1126, 2008; Section on Ophthalmology American Academy of Pediatrics; American Academy of Ophthalmology, American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus: Screening examination of premature infants for retinopathy of prematurity, Pediatrics 117:572-576, 2006.

Common Neonatal Conditions

Common Neonatal Conditions

Erythema Toxicum

Description and Epidemiology

Firm, yellow-white 1- to 2-mm papules or pustules with a surrounding erythematous flare characterize erythema toxicum. Lesions are clustered in several sites. These lesions usually develop at 24 to 48 hours old. The cause is unknown, although examination of a Wright-stained smear of the lesion reveals numerous eosinophils. Up to 50% of infants develop erythema toxicum, with a higher incidence in term than in premature infants.

Differential Diagnosis

Pyoderma, candidiasis, herpes simplex, transient neonatal pustular melanosis, and miliaria should be considered (Table 38-3).

TABLE 38-3 Comparison of Erythema Toxicum and Herpes Simplex Virus

| Erythema Toxicum | Herpes Simplex Virus |

|---|---|

| Benign, self-limited | Pathologic, progressive |

| No specific maternal history | Frequently a history of maternal disease |

| Usually seen only in term infant | Can occur in infants of any gestational age |

| Begins on the second or third day of life, lasting as long as 1 week | Often begins late in the first week of life or early in the second week of life |

| Rash is evanescent, often involving the face, trunk, and extremities | Can be superficial and localized only to the presenting part (vertex or buttocks) or widespread and disseminated with or without cutaneous involvement |

| 1- to 2-mm white papules or pustules on an erythematous base that occasionally may become somewhat vesicular | May manifest similar to sepsis without cutaneous findings or as grouped vesicles on an erythematous base on the presenting part about days 9-11 of life |

| Wright or Giemsa stain of lesion scraping demonstrates large numbers of eosinophils and no organisms; cultures are sterile | DFA staining or ELISA detection of HSV antigens of vesicle scrapings or growth of the organism from vesicle fluid is diagnostic |

| No specific therapy necessary | Acyclovir and other antiviral agents |

DFA, Direct fluorescent antibody; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; HSV, herpes simplex virus.

Cutis Marmorata

Description and Epidemiology

Cutis marmorata is a lacy, reticulated, red or blue cutaneous vascular pattern appearing over most of the body surface. The vascular change is a response to exposure to low environmental temperatures. It represents an accentuated physiologic vasomotor response that disappears with increasing age. Persistent and pronounced cutis marmorata occurs in Down and trisomy 18 syndromes.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree