Chapter 21 Pelvic Pain

Dysmenorrhea

Dysmenorrhea

PRIMARY DYSMENORRHEA

Pathophysiology

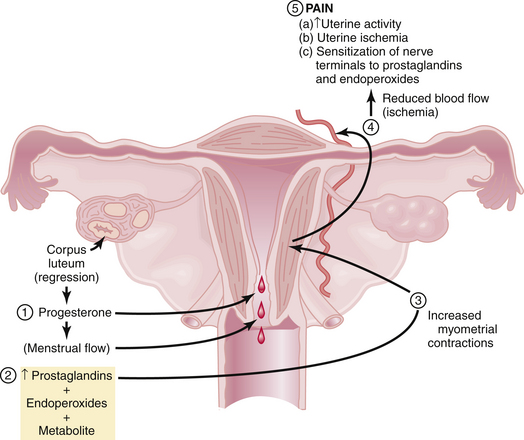

Figure 21-1 summarizes the relationships among endometrial cell wall breakdown, prostaglandin synthesis, uterine contractions, ischemia, and pain.

Clinical Features

The clinical features of primary dysmenorrhea are summarized in Box 21-1. Cramping usually begins a few hours before the onset of bleeding and may persist for hours or days. It is localized to the lower abdomen and may radiate to the thighs and lower back. The pain may be associated with altered bowel habits, nausea, fatigue, dizziness, and headache.

Treatment

Box 21-2 lists the treatment options for primary dysmenorrhea. NSAIDs, which act as COX inhibitors, are highly effective in the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea. Typical examples include ibuprofen (400 mg every 6 hours), naproxen sodium (250 mg every 6 hours), and mefenamic acid (500 mg every 8 hours). Decreasing prostaglandin production by enzyme inhibition is the basis of all NSAIDs. Hormonal contraceptives such as oral contraceptive pills (OCs), patches, or transvaginal rings reduce menstrual flow and inhibit ovulation and are also effective therapy for primary dysmenorrhea. Extended cycle use of OCs or the use of long-acting injectable or implantable hormonal contraceptives or progestin-containing intrauterine devices minimizes the number of withdrawal bleeding episodes that users have. Some patients may benefit from using both hormonal contraception and NSAIDs.

SECONDARY DYSMENORRHEA

Clinical Features

The clinical features of some of the underlying causes of secondary dysmenorrhea are summarized in Box 21-3. In general, secondary dysmenorrhea is not limited to the menses and can occur before as well as after the menses. In addition, secondary dysmenorrhea is less related to the first day of flow, develops in older women (in their 30s or 40s), and is usually associated with other symptoms such as dyspareunia, infertility, or abnormal uterine bleeding.

Acute Pelvic Pain

Acute Pelvic Pain

Acute pain is sudden in onset and is usually associated with significant neuroautonomic reflexes such as nausea and vomiting, diaphoresis, and apprehension. It is important for the gynecologist to be aware of both the gynecologic and nongynecologic causes of acute pelvic pain (Box 21-4). Delay of diagnosis and treatment of acute pelvic pain increase the morbidity and even mortality.

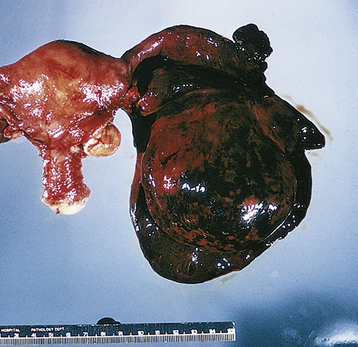

Adnexal accidents, including torsion or rupture of an ovarian (Figure 21-2) or fallopian tube cyst, can cause severe lower abdominal pain. Normal ovaries and fallopian tubes rarely undergo torsion, but cystic or inflammatory enlargement predisposes to these adnexal accidents. The pain of adnexal torsion can be intermittent or constant, is often associated with nausea, and has been described as reverse renal colic because it originates in the pelvis and radiates to the loin. An enlarging pelvic mass is found on examination and ultrasound with decreased or absent blood flow to the adnexa on Doppler ultrasound studies. The need for surgical intervention is common and urgent.

FIGURE 21-2 Torsion of an ovarian cyst.

(From Clement PB, Young RH: Atlas of Gynecologic Surgical Pathology. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 2000.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree