12 GRETCHEN EVANS PARKER, JEAN W. SOLOMON and JANE CLIFFORD O’BRIEN After studying this chapter, the reader will be able to accomplish the following: • Describe the characteristics of a variety of pediatric conditions. • Describe the signs and symptoms of pediatric orthopedic, genetic, neurologic, developmental, cardiopulmonary, neoplastic, sensory and environmentally induced conditions. • Describe the types and classification of burns. • Describe treatment precautions associated with specific pediatric conditions. • Summarize the ways in which different conditions affect children’s and adolescent’s occupational performance. • Describe general intervention principles and strategies associated with pediatric health conditions or diagnoses. • Describe the roles of the occupational therapy assistant and the occupational therapist in interventions for children with a variety of diagnoses. • Use knowledge of pediatric conditions to plan interventions. This chapter describes the major characteristics, signs and symptoms, and intervention strategies of a variety of pediatric conditions encountered by occupational therapy (OT) practitioners. Knowing the course and characteristics of each of these conditions serves as a framework for assessment, evaluation, and intervention planning. This knowledge enables the OT practitioner to be a valuable member of the intervention team. Box 12-1 lists some potential members of the pediatric team. Orthopedic or musculoskeletal conditions involve bones, joints, and muscles. The musculoskeletal system consists of the skeletal and muscular systems. The skeletal system consists of bones, joints, cartilage, and ligaments. The muscular system consists of muscles, tendons, and the fascia covering them (Box 12-2). Tendons, which are bands of tough, inelastic fibrous tissue, connect muscles to bones. Muscles are activated by the nervous system and move bone(s) to create movement at a joint. Arthrogryposis is sometimes genetic but is also attributed to reduced amniotic fluid during gestation or central nervous system (CNS) malformations.39 In the classic form of arthrogryposis, all the joints of the extremities are stiff, but the spine is not affected. Shoulders are turned in, elbows are straight, and wrists are flexed, with ulnar deviation. Hips may be dislocated, and knees are straight, with the feet turned in. Arm and leg muscles are small, with webbed skin covering some or all of the joints. The condition is worse at birth, so any increases in ROM or joint motion are improvements.4 In typical cases, all the joints of the arms and legs are fixed in one position, partly due to muscle imbalance or lack of muscle development during gestation (Figure 12-1). Ongoing occupational and physical therapies help children with arthrogryposis meet educational, self-care, and play needs. Children with arthrogryposis have many physical limitations that interfere with all areas of occupational performance. OT practitioners may help these children maintain or increase ROM and adapt themselves to perform their occupations and daily activities. OT practitioners may elect to use technology to help these children engage in ADLs, play, education, and social participation (see Chapter 26). Due to the multiple issues associated with arthrogryposis, OT practitioners consult with family members and school personnel to provide the best intervention. The following case example illustrates some intervention principles. The three types of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA) are (1) Still’s disease (20% of JRA cases), (2) pauciarticular arthritis (40% of JRA cases), and (3) polyarticular arthritis (40% of JRA cases) (Table 12-1).5,10 Children with JRA experience exacerbations and remissions of symptoms. During exacerbations, or flareups, symptoms worsen, and the joints become hot and painful; joint damage can occur. During remissions, or pain-free periods, children with JRA may resume typical activities. Joint protection techniques are encouraged at all times so that these strategies become a habit (Box 12-3). TABLE 12-1 Three Types of Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis JRA, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Data from Rogers, S. Common conditions that influence children’s participation. In Case-Smith J, O’Brien J: Occupational therapy for children, ed 6, St. Louis, 2010, Mosby, pp. 153-154.Arthritis Foundation: http://www.arthritis.org/disease-center.php?disease_id=38&df=effects : Accessed June 14, 2010. . By the time they are adults, 75% of individuals with JRA have permanent remission.12 However, these children may have functional limitations due to contractures and deformities. The OT practitioner helps educate them on how to protect their joints, compensate for lack of ROM during exacerbations, and complete activities with less stress on the joints (work simplification techniques). Furthermore, the OT practitioner provides these children with stretching and movement activities to maintain the functioning of the joints and prevent contractures. The OT practitioner may prescribe adaptive equipment or technology to help these children engage in everyday activities (Box 12-4). Congenital hip dysplasia (or dislocation of the hip) may be caused by genetic or environmental factors. An infant may be genetically prone to instability of one or both of the hip joints, and sudden passive stretching of an unstable hip or prolonged time in a position that makes the hip vulnerable may cause a dislocation.14,35 Medical intervention at an early age is critical to preventing permanent physical or body structure damage. Surgery may be necessary. Less invasive procedures, such as bracing and casting, may promote proper hip alignment and stability (Figure 12-2). An infant born missing all or part of a limb has a congenital amputation. A traumatic amputation is the result of an accident, infection, or cancer. Each year, approximately 26 out of 10,000 children in the United States are born missing all or part of a limb. The types of amputations vary greatly (Table 12-2). Thumb and below-elbow amputations are the most common types of upper extremity congenital amputations.12 TABLE 12-2 Types of Congenital Upper Extremity Amputations Data adapted from Rothstein JM, Roy HR, Wolf SL: The rehabilitation specialist’s handbook, ed 2, Philadelphia, 1998, FA Davis. Fitting a prosthesis on a child with a congenital amputation at a very young age allows the child to reach developmental milestones in a timely manner and for the prosthesis to become a part of the child’s body image. A prosthesis is more likely to be rejected when the child is older. In the case of a less severe congenital amputation, a child often does well without a prosthesis. The use of a prosthesis depends on the severity of the amputation and whether one or both arms are involved. See Box 12-5 for stump and prosthesis care. Children with orthopedic conditions may exhibit difficulty performing ADLs, instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), education, play, or social participation because of improper joint alignment. For example, children with achondroplasia often have difficulty grasping and manipulating objects because of their short but large hands. They benefit from practice, modification, and adaptation (Table 12-3). They may need work space modifications (e.g., adapted chairs). Furthermore, their physical stature may interfere with play. Children with JRA may develop contractures that limit their active ROM and interfere with their ability to perform play, leisure, and academic activities and ADLs. They benefit from stretching exercises and work simplification techniques. TABLE 12-3 Orthopedic Conditions: General Intervention Considerations OT interventions for orthopedic conditions frequently involve the following: • Helping children engage in all areas of occupation (e.g., play, ADLs, education, social participation, IADLs) • Developing home programs to facilitate engagement in occupations that can easily be integrated into the child’s and family’s daily activities • Providing passive or active stretching exercises to improve ROM for occupations. This may be accomplished through activities, orthoses, or casting. OT practitioners may design orthoses to help with the alignment of joints. Clinicians frequently consult with orthopedists to explore the functional outcome of the orthotic, or procedure • Providing work simplification/joint protection techniques to rest inflamed joints and to protect joints • Adapting equipment to compensate for limited ROM or congenital anomalies • Providing compensatory techniques to allow children to succeed by performing their occupations differently • Remediation to strengthen muscles and stability around the joints Approximately 30% of developmental disabilities are related to genetic conditions; 50% of major hearing and vision problems are caused by genetic syndromes.12 The descriptions that follow highlight genetic conditions commonly encountered in OT practice. Table 12-4 and Box 12-6 provide an overview of other selected genetic disorders and the signs and symptoms or genetic disorders. TABLE 12-4 One of the more common types of muscular dystrophy (MD) is Duchenne muscular dystrophy, or pseudohypertrophic (which means “false overgrowth”) MD. In children with Duchenne MD, the muscle mass breaks down and is replaced by fat and scar tissue. The buildup of fat and scar tissue can make the muscles, especially those of the calves, look unusually large. Duchenne MD is seen only in boys. About 3 individuals per 100,000 develop the condition.12 Most children who have Duchenne MD survive until they are in their 20s, and a few live until they are in their 30s. The cause of death is usually cardiopulmonary system (heart and lung) complications that lead to pneumonia. Sometimes parents suspect that something is wrong when their infant begins to walk on his toes around 1 year of age (Box 12-7). The diagnosis is usually made by the age of 4 years after a muscle biopsy is performed. By then the child’s calves look large and progressive weakness has begun, especially in the joints closest to the body. Scoliosis (Figure 12-3) can develop because of muscle weakness, especially during growth spurts. Proper wheelchair positioning and support are important to prevent scoliosis. Older children with Duchenne MD may have to use a ventilator, so good body alignment is important for maintaining chest capacity that is vital for breathing. One of 2000 infants born to women who are less than 40 years of age and 1 of 40 infants born to women who are more than 40 years old have Down syndrome. About 95% of the individuals with Down syndrome have an extra twenty-first chromosome. The extra chromosome comes from the father 25% to 30% of the time.10 Early intervention, including occupational, speech, physical, and developmental therapies are an important part of helping children with Down syndrome reach their full potential. Recent research indicates that early intervention, including teaching families ways to enrich their children’s environment, helps reduce developmental delays.32 Children with Down syndrome have characteristic facial features (slanted eyes, skin fold over nasal corners of eyes, small mouth, protruding tongue), tendency for cardiac anomalies, low muscle tone throughout, intelligence deficits, and simian creases in hands See Figure 12-4. (Box 12-8). Cri du chat syndrome (cri du chat means “cry of the cat”) is a rare genetic condition caused by the absence of part of chromosome 5. The baby or the young child with this genetic disorder has a weak, mewing cry. Classic body features documented in children with cri du chat syndrome include microencephaly; widely spaced, down-slanting eyes; cardiopulmonary abnormalities; and failure to thrive.9 Children with cri du chat syndrome experience intellectual deficits and developmental delays . Fragile X syndrome affects boys more often than girls. Children present with limited brain development, abnormal skull, joints, and feet structures.19 They exhibit typical structural features, including elongated faces, prominent jaws and foreheads, hypermobile or lax joints, and flat feet. Children with fragile X syndrome may be intellectually delayed. Prader-Willi syndrome involves chromosome 15. Children and adolescents who have Prader-Willi syndrome exhibit varying degrees of intellectual deficits, overeating habits, and self-mutilating behaviors such as picking sores until they bleed or biting their fists until large calluses develop.20 OT practitioners working with children with genetic or chromosomal disorders address the occupational performances of these children (Table 12-5). For example, children with fragile X syndrome may have intellectual disabilities and thus will require assistance to develop ADL skills. They may require adaptations to be independent, structure to engage in leisure activities, and training to participate in work. Children and adolescents with Prader-Willi syndrome require intervention for social participation because their behaviors such as picking sores and overeating are not socially acceptable. OT practitioners may provide the families of these children with strategies to help their children function to their full potential. TABLE 12-5 Genetic and Chromosomal Disorders: General Intervention Considerations OT interventions for genetic or chromosomal conditions frequently involve the following: • Analysis of occupational performance, including the child’s strengths and weaknesses and how this influences the child’s performance • Developmental interventions to facilitate achievement of milestones and to promote occupational performance • Interventions to increase strength and endurance for activities • Behavioral modification techniques to develop socially appropriate behaviors • Task-specific activities to teach child-specific skills for daily living • Adaptations or compensation for limited problem-solving, memory, or generalization abilities

Pediatric health conditions*

Orthopedic conditions

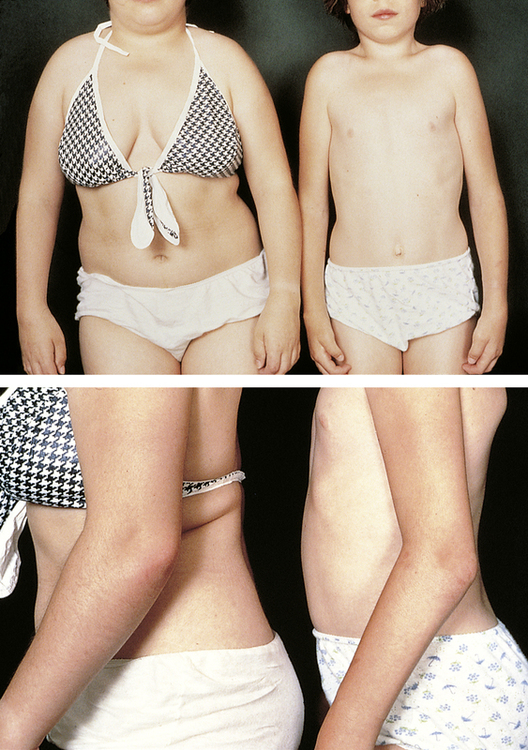

Arthrogryposis

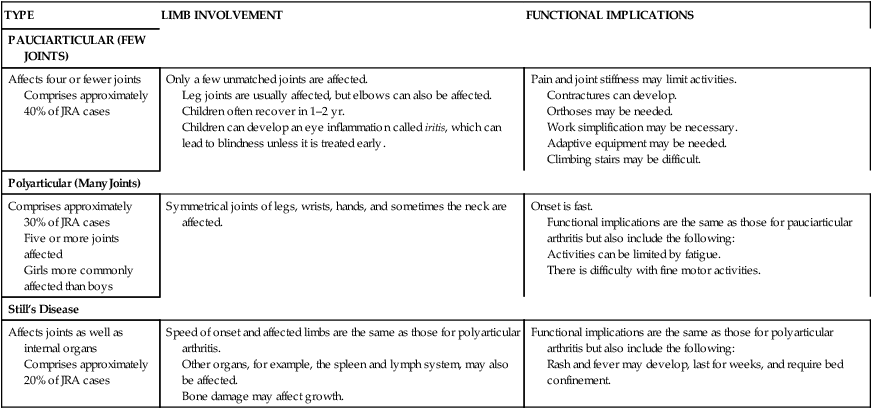

Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis

TYPE

LIMB INVOLVEMENT

FUNCTIONAL IMPLICATIONS

PAUCIARTICULAR (FEW JOINTS)

Affects four or fewer joints

Comprises approximately 40% of JRA cases

Only a few unmatched joints are affected.

Leg joints are usually affected, but elbows can also be affected.

Children often recover in 1–2 yr.

Children can develop an eye inflammation called iritis, which can lead to blindness unless it is treated early.

Pain and joint stiffness may limit activities.

Contractures can develop.

Orthoses may be needed.

Work simplification may be necessary.

Adaptive equipment may be needed.

Climbing stairs may be difficult.

Polyarticular (Many Joints)

Comprises approximately 30% of JRA cases

Five or more joints affected

Girls more commonly affected than boys

Symmetrical joints of legs, wrists, hands, and sometimes the neck are affected.

Onset is fast.

Functional implications are the same as those for pauciarticular arthritis but also include the following:

Activities can be limited by fatigue.

There is difficulty with fine motor activities.

Still’s Disease

Affects joints as well as internal organs

Comprises approximately 20% of JRA cases

Speed of onset and affected limbs are the same as those for polyarticular arthritis.

Other organs, for example, the spleen and lymph system, may also be affected.

Bone damage may affect growth.

Functional implications are the same as those for polyarticular arthritis but also include the following:

Rash and fever may develop, last for weeks, and require bed confinement.

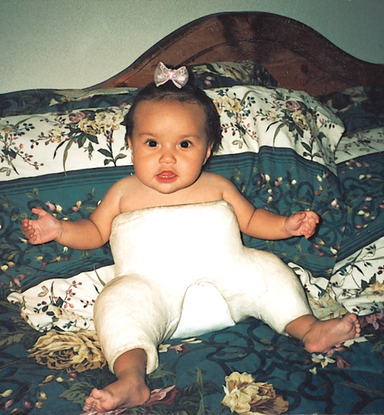

Congenital hip dysplasia

Amputation

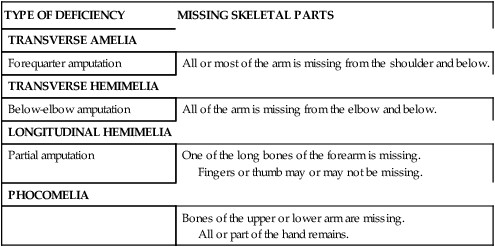

TYPE OF DEFICIENCY

MISSING SKELETAL PARTS

TRANSVERSE AMELIA

Forequarter amputation

All or most of the arm is missing from the shoulder and below.

TRANSVERSE HEMIMELIA

Below-elbow amputation

All of the arm is missing from the elbow and below.

LONGITUDINAL HEMIMELIA

Partial amputation

One of the long bones of the forearm is missing.

Fingers or thumb may or may not be missing.

PHOCOMELIA

Bones of the upper or lower arm are missing.

All or part of the hand remains.

General interventions

CONSIDERATION

DEFINITION AND EXAMPLE(S)

Promotion of proper joint alignment

Through static (nonmovement) and dynamic (movement) orthotic devices, facilitating the typical alignment of muscles and joints. (Note: In the absence of soft tissue contracture and/or bony deformities)

Application modalities such as ice or moist heat

Placing a moist heat pack or ice pack on the inflamed area

Immobilization with a cast or orthosis

Keeping the involved area in proper alignment

Instruction in proper positioning to reduce edema or swelling

Elevating the involved/inflamed area to increase flow of body fluids back to the trunk

Compensation

Helping the child engage in occupations through changing the ways or techniques used to participate

Modification/adaptation

Helping the child participate in occupations by changing how the activities are performed

Emotional/psychosocial consideration

Addressing emotional/psychosocial issues associated with disorders. Children may need to work on developing a positive self-concept, body awareness, and sense of control

Social participation

Promoting social participation in children

Genetic conditions

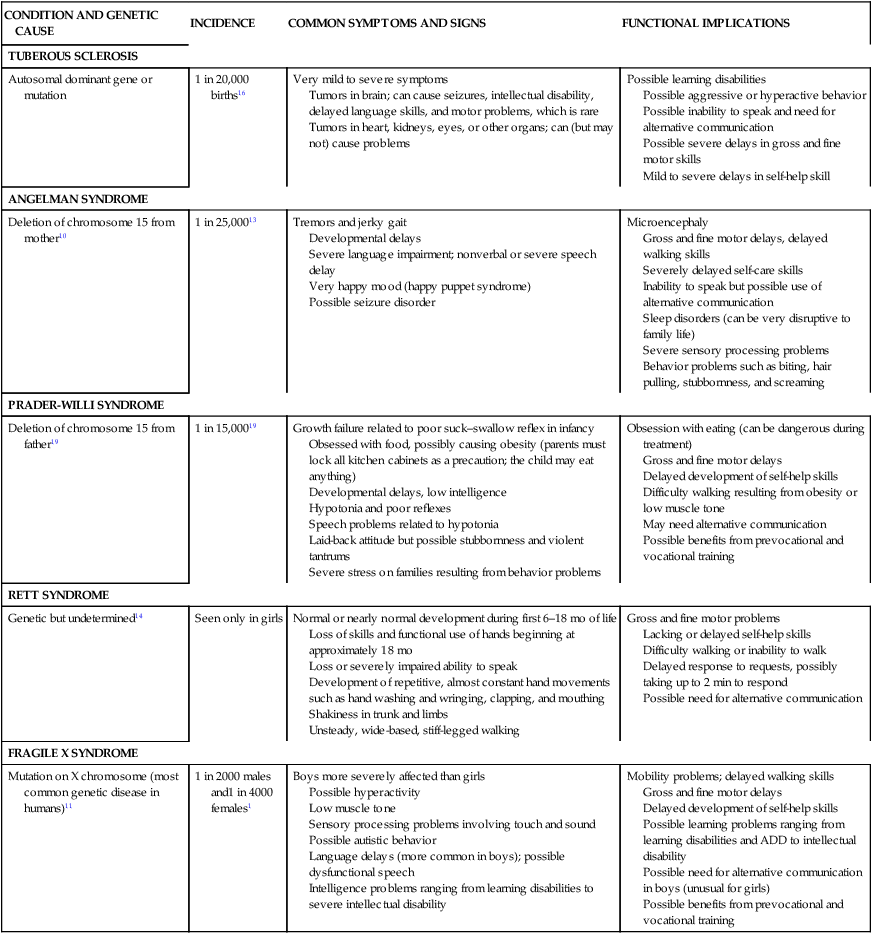

CONDITION AND GENETIC CAUSE

INCIDENCE

COMMON SYMPTOMS AND SIGNS

FUNCTIONAL IMPLICATIONS

TUBEROUS SCLEROSIS

Autosomal dominant gene or mutation

1 in 20,000 births16

Very mild to severe symptoms

Tumors in brain; can cause seizures, intellectual disability, delayed language skills, and motor problems, which is rare

Tumors in heart, kidneys, eyes, or other organs; can (but may not) cause problems

Possible learning disabilities

Possible aggressive or hyperactive behavior

Possible inability to speak and need for alternative communication

Possible severe delays in gross and fine motor skills

Mild to severe delays in self-help skill

ANGELMAN SYNDROME

Deletion of chromosome 15 from mother10

1 in 25,00013

Tremors and jerky gait

Developmental delays

Severe language impairment; nonverbal or severe speech delay

Very happy mood (happy puppet syndrome)

Possible seizure disorder

Microencephaly

Gross and fine motor delays, delayed walking skills

Severely delayed self-care skills

Inability to speak but possible use of alternative communication

Sleep disorders (can be very disruptive to family life)

Severe sensory processing problems

Behavior problems such as biting, hair pulling, stubbornness, and screaming

PRADER-WILLI SYNDROME

Deletion of chromosome 15 from father19

1 in 15,00019

Growth failure related to poor suck–swallow reflex in infancy

Obsessed with food, possibly causing obesity (parents must lock all kitchen cabinets as a precaution; the child may eat anything)

Developmental delays, low intelligence

Hypotonia and poor reflexes

Speech problems related to hypotonia

Laid-back attitude but possible stubbornness and violent tantrums

Severe stress on families resulting from behavior problems

Obsession with eating (can be dangerous during treatment)

Gross and fine motor delays

Delayed development of self-help skills

Difficulty walking resulting from obesity or low muscle tone

May need alternative communication

Possible benefits from prevocational and vocational training

RETT SYNDROME

Genetic but undetermined14

Seen only in girls

Normal or nearly normal development during first 6–18 mo of life

Loss of skills and functional use of hands beginning at approximately 18 mo

Loss or severely impaired ability to speak

Development of repetitive, almost constant hand movements such as hand washing and wringing, clapping, and mouthing

Shakiness in trunk and limbs

Unsteady, wide-based, stiff-legged walking

Gross and fine motor problems

Lacking or delayed self-help skills

Difficulty walking or inability to walk

Delayed response to requests, possibly taking up to 2 min to respond

Possible need for alternative communication

FRAGILE X SYNDROME

Mutation on X chromosome (most common genetic disease in humans)11

1 in 2000 males and1 in 4000 females1

Boys more severely affected than girls

Possible hyperactivity

Low muscle tone

Sensory processing problems involving touch and sound

Possible autistic behavior

Language delays (more common in boys); possible dysfunctional speech

Intelligence problems ranging from learning disabilities to severe intellectual disability

Mobility problems; delayed walking skills

Gross and fine motor delays

Delayed development of self-help skills

Possible learning problems ranging from learning disabilities and ADD to intellectual disability

Possible need for alternative communication in boys (unusual for girls)

Possible benefits from prevocational and vocational training

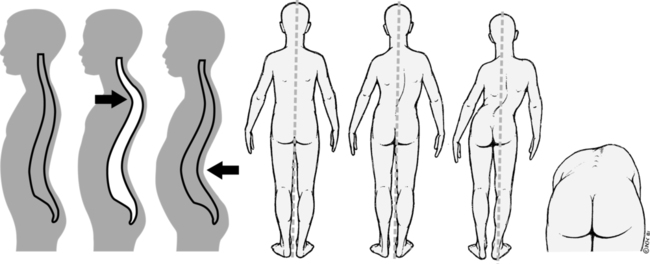

Duchenne muscular dystrophy

Down syndrome

Cri du chat syndrome

Fragile X syndrome

Prader-willi syndrome

General interventions

CONSIDERATION

DEFINITION AND EXAMPLE(S)

Failure to thrive

Many genetic disorders have associated feeding difficulties. These may be due to motor, cognitive, or structural functions. The OT practitioner should evaluate and treat them through training, compensation, adaptive technology, or remediation.

Developmental delays

Many genetic disorders have associated delays in motor, social, language, and self-care skills. OT practitioners can help children learn the skills needed for their occupations through intervention.

Cognitive delays

Lower cognitive abilities are frequently a part of genetic disorders. Children may learn skills at a slower rate and may show difficulty in problem solving and with abstract thought and reasoning. Practicing occupations in a variety of contexts helps children generalize skills.

Congenital anomalies

Children with genetic disorders may exhibit certain physical features (short stature, flat hand arches) which interfere with motor skills. OT practitioners can help them compensate or adapt to perform occupations.

Psychosocial/emotional issues

Children with genetic disorders also experience a range of emotional and psychological issues. OT practitioners can help them cope with everyday situations, deal with periods of stress, adapt to life changes, and work with their strengths.

Social participation/behaviors

OT practitioners work with children, families, and communities to help the children engage in occupations. Children with all levels of ability benefit from social participation. OT practitioners can assist them in fitting into groups by helping them develop socially appropriate behaviors.

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Pediatric health conditions

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue