Chapter 11

Patient Safety and Team Training

David J. Birnbach MD, MPH, Eduardo Salas PhD

Chapter Outline

In 2000, the publication of the Institute of Medicine (IOM) report To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health Care System was a seminal event for the health care system in the United States.1 Prior to the publication of this report, many physicians and hospital administrators refused to acknowledge the frequent occurrence of preventable morbidity and the reality that our health care system was not adequately addressing the issue of patient safety. Subsequently, we have learned that tens of thousands of patients die each year as a result of medical errors. In the past decade, numerous changes have been advocated, including mandating minimum nurse-to-patient ratios,2 reducing working hours of resident physicians,3 and advancing the science of simulation training and teamwork, particularly in the medical environment.4,5 Data from high-risk organizations suggest that health care errors do not usually occur because of ill-trained medical personnel but rather are due to systems that “set up” both the patient and the health care provider. As Pratt6 eloquently stated in a 2012 review of simulation in obstetric anesthesia, “Historically, medicine was simple, largely ineffective, and mostly safe (excluding perhaps trephination and bloodletting). Modern medicine is complex, highly effective, but dangerous.” The field of patient safety attempts to reduce that danger, which is very real in the fields of obstetrics and obstetric anesthesiology. Each year in the United States, approximately 600 women die of pregnancy-related causes; 68,000 experience severe obstetric morbidity; and 1.7 million experience delivery-related complications.7 In this chapter, medical errors are reviewed and several modalities that can be used by labor and delivery unit personnel to reduce both the incidence and sequelae of these errors are highlighted.

Patient Safety and Medical Errors

Traditional assessments of medical error often blamed individuals and have failed to address the broader systems issues that allowed the error to occur. Newer approaches are based on an understanding that humans will make errors and therefore encourage creation of robust systems to prevent these errors from occurring or to minimize their impact on patients if they occur. This paradigm change has borrowed heavily from other high-risk arenas, such as the aviation and the nuclear industries.

The Swiss Cheese Model

Patients are typically not injured by a single event resulting from a single act of a careless individual. More often an underlying systems problem made the error possible, and numerous individual actions “fall through the cracks” of a system that does not catch them, resulting in error and harm. James Reason described the “Swiss cheese” model of error (Figure 11-1), in which he explained how numerous contributing factors are responsible for the ultimate harm.8 Reason developed this model to illustrate how analyses of major accidents and catastrophic systems failures tend to reveal multiple, smaller failures that led up to the actual adverse event. In the model, each slice of cheese represents a safety barrier or precaution relevant to a particular hazard. For example, if the hazard were wrong-site surgery, slices of the cheese might include processes for identifying the right or left side on radiology tests, a protocol for signing the correct site when the surgeon and patient first meet, and a second protocol for reviewing the medical record and checking the previously marked site in the operating room. Each barrier has “holes”; hence, the term Swiss cheese. For some serious events (e.g., operating on the wrong person) the holes will rarely align; however, even rare cases of harm are unacceptable. Reason’s model highlights the need to think of safety as a system—a set of organizational and cultural layers that influence and shape one another. Reason has eloquently summarized the process, stating “rather than being the main instigators of an accident, operators tend to be the inheritors of system defects created by poor design, incorrect installation, faulty maintenance, and bad management decisions. Their part is usually that of adding the final garnish to a lethal brew whose ingredients have already been long in the cooking.”9

FIGURE 11-1 Swiss cheese model of organizational accidents. (From Reason JT. Human Error. Cambridge, UK, Cambridge University Press, 1990.)

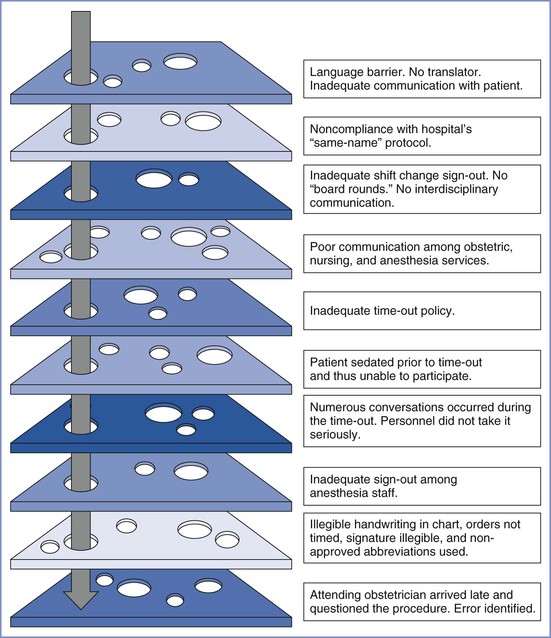

Figure 11-2 illustrates the use of the Swiss cheese model to evaluate a real near-miss case involving the misidentification of an obstetric patient who nearly underwent the wrong procedure (an unwanted tubal ligation). It describes how the combination of numerous system errors came very close to allowing the wrong procedure to be performed. The events unfolded as follows:

FIGURE 11-2 “Swiss cheese” diagram of near-miss event illustrating how numerous layers/barriers to harm were breached and how these events almost resulted in permanent harm (permanent sterility) to the patient. See text for explanation.

As in many such situations, a conglomeration of many missteps resulted in the potential for patient harm.

Medical Errors

Today there is widespread interest in changing the health care culture to build safer systems, including ensuring the appropriate physical work environment, developing redundancies in safety procedures, allowing health care workers to report their mistakes (including near misses) without fear of punishment, and providing mechanisms to learn from the experiences. None of these systems will achieve the ultimate goal of patient safety without the support of physicians as well as hospital administrators. In addition, although vital to improving the current condition, these steps do not obviate the need for well-trained and well-rested physicians and nurses. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Committee Opinion on Patient Safety in the Surgical Environment summarizes this well when it states: “Common sense dictates that the surgeon and the surgical team should be alert and well rested when initiating major surgical procedures.”10 The opinion also suggests that “adequate backup personnel should be available to relieve individuals who detect diminished performance in themselves or others due to fatigue, so that the risk for error is not increased.”10 Although the Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education has enacted restrictions on resident physician work hours to prevent sleep deprivation, there are no such limits on attending physician work hours. Rothschild et al.11 found that the risk for surgical complications was increased if attending physicians had slept less than 6 hours the night before the procedure.

Another ACOG committee opinion12 stated that promoting safety requires that all those in the health care environment recognize that the potential for errors exists and that women’s health care should be delivered in an environment that encourages disclosure and exchange of information in the event of errors, near misses, and adverse outcomes. The ACOG12 has recommended the following seven safety objectives:

1. Develop a commitment to encourage a culture of patient safety.

2. Implement recommended safe medication practices.

3. Reduce the likelihood of surgical errors.

4. Improve communication with health care providers.

5. Improve communication with patients.

6. Establish a partnership with patients to improve safety.

The IOM has defined medical error as a “failure of a planned action to be completed as intended, or the use of a wrong plan to achieve an aim.” Communication problems are consistently identified as a leading cause of medical errors in obstetrics,13 and the Joint Commission has found that although the majority of these events have multiple root causes, lack of effective communication along with leadership and human factors are often the primary causes of sentinel events.14 Several of the 2012 Joint Commission National Patient Safety Goals relate to error reduction on the labor and delivery unit (Box 11-1).15 Departments of anesthesiology and obstetrics and gynecology should regularly review the national patient safety goals established by the Joint Commission. Hospitals are regularly surveyed to verify their compliance with these goals.

Although those working in health care have made great efforts to reduce preventable patient harm,16 the progress has not been as dramatic as necessary. Leape and Berwick, two “fathers” of the field of patient safety, suggested that the lack of progress following the release of the initial IOM report is due to the “culture of medicine.”17 They believe that this culture is deeply rooted, both by custom and training, in autonomous individual performance. It remains possible that systematic and appropriate use of medical simulation, along with other important changes to our systems, will facilitate the necessary cultural changes and lead to improved patient safety. Labor and delivery units are no different than other medical care environments, and most still have many opportunities to change culture and practice to optimize patient safety. Nabhan and Ahmed-Tawfik18 suggested that the concept of patient safety in obstetrics is “not as strong as desirable for the provision of reliable health care.” In many units a punitive culture still exists and results in suppression of error reporting, lack of proper communication, and failure of appropriate feedback.18 Obviously, this culture needs to change before we can significantly improve patient safety. Pronovost and Freishlag19 eloquently described the operating room environment when they stated that “operating rooms are among the most complex political, social, and cultural structures that exist, full of ritual, drama, hierarchy, and too often conflict.” These authors concluded that poor teamwork contributes prominently to most adverse events, including those in the operating room.19

Teams and Teamwork

Health care should be considered a team activity. Teams take care of patients. Furthermore, health care teams operate in an environment characterized by acute stress, heavy workload, and high stakes for decision and action errors.20 Individuals have limited capabilities; when their limitations are combined with organizational and environmental complexity, human error is virtually inevitable.21 The labor and delivery unit is an exceedingly complex environment. In fact, the labor and delivery unit requires intense, error-free vigilance with effective communication and teamwork among various clinical disciplines who, although working together, have probably never trained together. This group includes obstetricians, midwives, nurses, anesthesiologists and nurse anesthetists, and pediatricians. The addition of trainees at all levels and in all disciplines enhances the potential for communication error. Siassakos et al.22 suggested that one of the most important components of effective training in obstetrics includes multiprofessional training and integration of teamwork training with clinical teaching.

A team consists of two or more individuals who have specific roles, perform independent tasks, are adaptable, and share common goals. Salas et al.23 have defined teamwork as a complex yet elegant phenomenon. It can be defined as a “set of interrelated behaviors, actions, cognitions, and attitudes that facilitate the required task work that must be completed.”23 Lack of teamwork has been identified as a leading cause of adverse events in medicine. Team behavior and coordination, particularly communication or team information sharing, are critical for optimizing team performance.24 Baker et al.25 stated that to work together effectively, team members must possess specific knowledge, skills, and attitudes (KSAs), including skill in monitoring each other’s performance, knowledge of their own and their teammates’ task responsibilities, and a positive disposition toward working in a team. These authors have described characteristics of effective teams, which include team leadership, mutual performance monitoring, backup behavior, adaptability, shared mental models, communication, team/collective orientation, and mutual trust. Moreover, effective team performance in complex environments requires that team members hold a shared understanding of the task, their equipment, and their teammates (Table 11-1).26,27

TABLE 11-1

Characteristics of Effective Teams

| Knowledge/Skills/Attitudes | Characteristics of the Team |

| Leadership | Roles are clear but not overly rigid. Team members believe leaders care about them. |

| Backup behavior | Members compensate for each other. Members provide feedback to each other. |

| Mutual performance monitoring | Members understand each other’s roles. |

| Communication adaptability | Members communicate often and anticipate each other. |

| Mutual trust | Members trust each other’s intentions. |

Modified from Salas E, Sims DE, Klein C. Cooperation and teamwork at work. In Spielberger CD, editor. Encyclopedia of Applied Physiology. San Diego, CA, Academic Press, 2004:499-505.

Teamwork is essential for safe patient care. The IOM suggested that team training and implementation of team behaviors may improve patient safety.28 The Joint Commission has recommended a risk-reduction strategy for decreasing perinatal death or injury. This strategy includes the implementation of team training and mock emergency drills for shoulder dystocia, emergency cesarean delivery, and maternal hemorrhage.29

Team training promotes the acquisition of adaptive behaviors, shared cognitions, and relevant attitudes. It is an instructional strategy that ideally combines practice-based delivery methods with realistic events, guided by medical teamwork competencies (i.e., behaviors, cognitions, and/or attitudes). Murray and Enarson30 stated that “when a crisis complicates patient care, teamwork among health care professionals is frequently strained, resulting in more frequent as well as more serious failures in managing critical events.” This scenario occurs all too often on the labor and delivery unit.

After many years of uncertainty, there is now encouraging evidence that team training improves safety of clinical outcomes, especially in the operating room31,32 and labor and delivery suite. Neily et al.32 reported that surgical mortality decreased by 18% at 74 United States Veterans Health Administration hospitals that implemented a team training program, compared with a 7% mortality reduction in 34 control hospitals that did not implement such a program. Nielson et al.33 reported that team training effectively reduced the decision-to-delivery time for emergency cesarean delivery. Similarly, after mandatory interdisciplinary team training for all labor and delivery staff in a unit in the United Kingdom, the median decision-to-delivery interval for a prolapsed umbilical cord decreased from 25 to 15 minutes. After initiation of team training in a community hospital, Shea-Lewis et al.34 reported a reduction in the adverse outcome index (AOI: a composite maternal and neonatal adverse outcome index35) from 7% to 4%.

Team Leadership

There is a clear difference between the leadership of individuals and team leadership. One who is leading independent individuals will diagnose a problem, generate possible solutions, and implement the most appropriate solution. In contrast, team leadership does not involve handing down solutions to team members but rather consists of defining team goals, setting expectations, coordinating activities, organizing team resources, and guiding the team toward its goals.36

Team leaders can improve team performance in many ways (e.g., by promoting coordination and cooperation). These individuals not only must be technically competent but also must be competent in leadership skills.20 Anesthesia providers and other physicians do not routinely train to be competent team leaders. Many of the tasks necessary can and must be learned during team training. Simulation may play a key role in this education. Team leadership training has been developed to successfully train specific team leader behaviors, and the implementation of these programs has been shown to improve team performance.23 Hackman37 described successful team performance as consisting of three primary elements:

1. Successful accomplishment of the team’s goals

2. Satisfaction of team members with the team and commitment to the team’s goals

3. The ability of the team to improve different facets of team effectiveness over time

High-Reliability Organizations and Teams

Despite the inevitability of human error, some organizations that operate in complex environments are able to maintain an exceptionally safe workplace. These organizations, including the aviation and nuclear power industries, have been termed high-reliability organizations (HROs). These organizations can also be hospitals and other health care organizations. Sundar et al.38 defined HROs as institutions where individuals, working together in high-acuity situations facing great potential for error and disastrous consequences, consistently deliver care with positive results and minimal errors. Teams that exhibit behaviors that facilitate the characteristics and values held by the HRO may be defined as high-reliability teams

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree