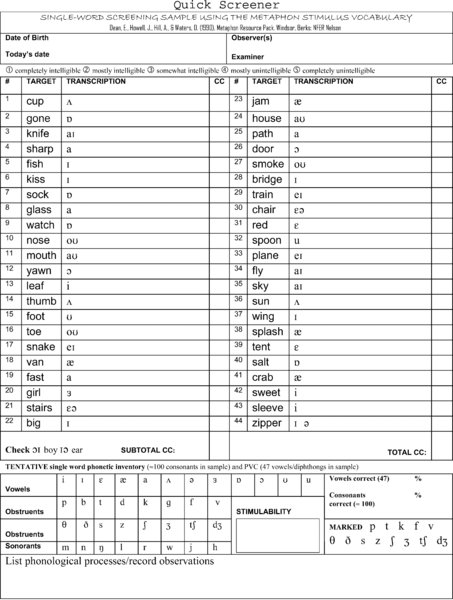

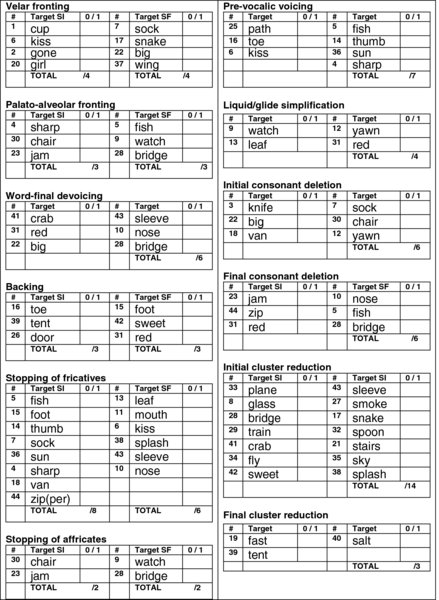

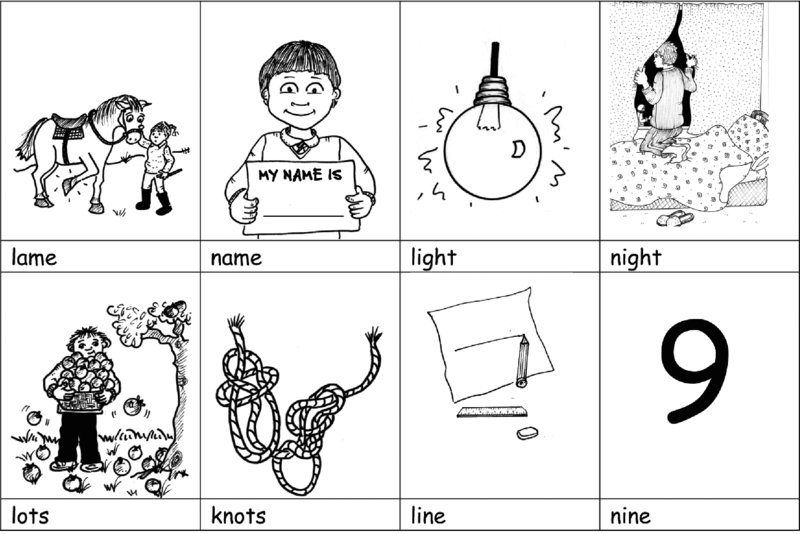

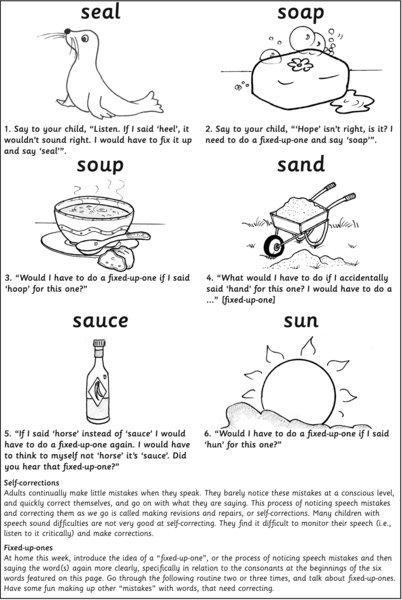

Chapter 9 PACT is an acronym for a family-centred phonological assessment and intervention approach to speech sound disorders called Parents and Children Together (Bowen, 2010; Bowen & Cupples, 2006). PACT could just as easily stand for ‘parents and child, and therapist’ and implies an arrangement in which all are actively involved in the intervention process, while the name itself reflects the child and family focus of the approach. Administered in planned blocks and breaks, PACT is termed ‘broad-based’ because, while concentrating mostly on the phonemic (phonological or cognitive–linguistic) level, it also takes account of phonetic and auditory perceptual factors. This is because the difficulties children diagnosed with phonological disorders experience may not be exclusively ‘phonological’. PACT directly targets speech perception and production, and hence intelligibility, in children with phonological disorder. It may also indirectly impact morphosyntax and phonological awareness (particularly phonemic awareness) and hence literacy acquisition. In Chapter 9, PACT is described and illustrated with a case study of Josie, augmented by a contribution by Debbie James in A50, relating to issues that arose. More PACT information can be accessed at www.speech-language-therapy.com. Click on the ARTICLES tab in the header of any page, and go to ‘Intervention’. On that page are links to four PACT-related pages: Implementation, Publications, Theory and Evidence and Therapy for Josie. On the latter page is a slide show about Josie’s intervention and progress, and links to activities and resources used in treating her severe phonological disorder that involved a mix of phonemic, perceptual and phonetic issues. PACT was designed for 3- to 6-year olds and validated as an effective treatment for children in this age range diagnosed with mild, moderate and severe phonological disorders (Bowen, 1996a; Bowen & Cupples, 1999a, b). The children in the efficacy study were typical of children with intelligibility difficulties in that they did not necessarily have ‘pure’ phonological disorder. Whereas children with language impairment, including SLI, were excluded from the study, and each of the children’s major communication difficulty was at the phonological level, the major contributing component was often accompanied by phonetic execution and auditory perceptual difficulties. Moreover, some participants were treated for stuttering (Unicomb, Hewat, Spencer & Harrison, 2013) during the intervention process. We had a twofold rationale for developing a therapy for pre-schoolers and younger school children. First, intelligibility difficulties may be obvious in 2- and 3-year olds (Dodd, A10; McIntosh & Dodd, 2011), but diagnosis of SSD is usually elusive until sometime in a child’s fourth year. Withholding intervention, however, until diagnosis is ‘definite’ can prove counterproductive in the longer term. Second, we wanted to develop an intervention that families could access before their children started formal schooling, potentially ‘catching’ many of the children before they were busy (and often tired) and inaccessible – in the sense of not wanting to miss school – to attend speech therapy, and pre-empting or minimising literacy acquisition difficulties. Clinicians have reported acceptable outcomes with PACT with other populations, but such implementation has not been tested experimentally. The ‘other’ children have included 3;0- to 6;11-year olds with language processing and production issues and SSD; and children with speech production issues ≤10 years with SLI; ≤10 years with pragmatic issues; growing up bilingual (and multilingual; Goldstein, A19; McLeod, Verdon & Bowen, 2013; Ray, 2002) and with developmental delay; as well as children with clefts, autism spectrum disorder, Down syndrome, Fragile X syndrome, Williams syndrome and cochlear implants. Although not designed specifically for children with CAS, it has been incorporated, with integral stimulation (Strand, Stoeckel & Baas, 2006), and compatible techniques that follow the principles of motor learning (Schmidt & Lee, 2011), to help treat children diagnosed with CAS. PACT is based on the assumptions that phonemic change is (1) gradual and motivated by homophony (Grunwell, 1987); (2) enhanced through metalinguistic awareness of phones (the phonetic level) and the phonemic system (the phonological level); and (3) facilitated by heightened perceptual saliency of contrasts because it increases their learnability. PACT embraces the foundations of all minimal pair approaches (Fey, 1992) by systematically modifying groups of sounds produced in error; emphasising the elimination of homophony (i.e., different words pronounced the same way) and the establishment of feature contrasts to mark meaning distinctions, rather than putting the spotlight on accurate sound production; and making it explicit to children that the function of phonology is communication. This is achieved in PACT by working at word level and above, using naturalistic parent–child communicative contexts, increasing the child’s (and parents’) metaphonological awareness, and targeting, as required, phonological, phonetic, phonotactic and perceptual goals. In the efficacy study, a longitudinal matched groups design was employed, with assessment, treatment and reassessment (probe) phases. Fourteen children were treated under typical clinical conditions, and treatment was withheld from eight matched children on waiting lists. At probe, the treated children showed accelerated and highly selective improvement in their productive phonology [F(1,20) = 19.36, P < 0.01], whereas the untreated eight did not. No such selective improvement was observed in the treated children in either receptive vocabulary or Mean Length of Utterance in Morphemes, attesting to the specific effect of the therapy. PACT is practicable (Robey & Schultz, 1998) under conditions of everyday practice in terms of the in-clinic component (Bowen & Cupples, 1998, 1999a), and it is feasible and often enjoyable for interested families implementing homework and follow-up away from the clinic (Bowen & Cupples, 2004). A 200-utterance conversational speech (CS) sample, or a 200-word CS sample, and single words (SWs) elicited using the Quick Screener (Bowen, 1996b, after Dean, Howell, Hill & Waters, 1990) usually provide sufficient data to allow independent and relational analyses (Stoel-Gammon, A9) and diagnosis, or provisional diagnosis, of phonological impairment. Additional testing is sometimes necessary, and this might entail administration of the DEAP (Dodd, Crosbie, Zhu, Holm & Ozanne, 2002) or the HAPP-3 (Hodson, 2004), the Locke Speech Perception Task (Locke, 1980; see Tables 8.6a and 8.6b), and an imitative PCC (Johnson, Weston & Bain, 2004). Speech assessment within the PACT approach, whether initial or ongoing, is integral to intervention. As parents play a central role in management, it is highly desirable for them to be aware—through observation, participation and explanation—of the speech-language assessment process. Essential components of data gathering are the case history interview; an audiological evaluation by an Audiologist; screening for language, pragmatics, voice and fluency strengths and difficulties; an oral musculature examination; and, as noted above, a CS sample of 200 utterances, if possible, remembering that, for some children, single word tokens may predominate. Within the case history interview, parents are asked to provide an intelligibility rating using a scale of 1–5: (1) completely intelligible; (2) mostly intelligible; (3) somewhat intelligible; (4) mostly unintelligible; and (5) completely unintelligible. This is recorded at the top of the Quick Screener data collection form displayed in Figure 9.1. Figure 9.1 The Quick Screener data collection form. From Bowen (1996b), after Dean et al. (1990). If the child’s output is so unintelligible that the clinician cannot even guess the content, or if time is short or the child’s cooperation difficult to establish, an imitative PCC procedure is used rather than the conversational PCC procedure (Flipsen Jr., A11). Johnson et al. (2004) found that PCCs derived from conversational samples did not differ significantly from PCCs drawn from sentence imitation, using age-appropriate vocabulary, syntax and representative distribution of speech sounds in children aged 4–6. They concluded that ‘the sentence imitation procedure offers a valid and efficient alternative to conversational sampling’. In their experiment, an almost wordless picture book, Carl Goes to Daycare (Day, 1993), provided visual stimuli for the repetition task, and the 36 short sentences, potentially containing 273 consonants, the children repeated after the examiner included, ‘Watch them dance’, ‘He got cold’, and ‘Time to go home’. Speech assessment begins with the administration of the Quick Screener, while parents observe, using the data collection form displayed in Figure 9.1. The SLP/SLT phonetically transcribes in full, with necessary diacritics, the child’s production of the first word ‘cup’ and immediately assigns a score that goes in the ‘CC’ (consonants correct) column. For example, if the child says [kɅp] the score is 2; if he or she says [kɅ], [Ʌp], [tɅp] or [ɡɅp] the score is 1; and if he or she says [Ʌ] or [tɅ] the score is zero. Each word is scored for consonant production in this way. There are approximately 100 consonants in the sample, depending on the dialect of English, so a tentative single-word PCC can be estimated quickly, with parents watching, by adding the figures in the CC columns and calling the sum a percentage. For example, if the child scores 55 consonants correct, his or her tentative PCC, or screening PCC, is 55%. There is also provision on the form to record vowel errors. The vowel and diphthong targets on the data collection form reflect non-rhotic Australian English. Therapists working with children speaking other varieties of English can change the vowel symbols, and ‘vowelless’ forms are available at www.speech-language-therapy.com. If the child mispronounces the vowel or diphthong in a word, the vowel or diphthong is circled by the therapist and later tallied to calculate a screening, single-word, percentage of vowels correct (PVC) using the formula VOWELS CORRECT ÷ 47 × 100 = PVC (again, while parents observe). It should be remembered that the PCC and the PVC derived from the screener are screening (tentative) measures, although it has been observed clinically that there is little variation in PCC and PVC scores between data gathered via the Quick Screener and larger data sets. Using the Quick Screener analysis form displayed in Figure 9.2, the clinician summarises the child’s phonological processes as percentages of occurrence, if this is considered useful, and records pertinent observations, including the therapist’s own intelligibility rating. These outcomes are discussed in the child’s hearing. It is explained to parents that the child’s continued presence during discussion demonstrates to the child that his or her parents are important partners in the therapy process. It also helps to acknowledge parents, up front, as the homework experts and experts where their own child is concerned. Figure 9.2 Quick Screener analysis form The word set contained in Quick Screener is based on the Metaphon Resource Pack Screening Test developed by Dean et al. (1990) with the word ‘gun’ changed to ‘gone’. The stimulus pictures, data collection forms and analysis form are freely available at www.speech-language-therapy.com. Word productions can be elicited using the Metaphon Resource Pack Screening Test easel book (now unfortunately out of print), or the Quick Screener pictures presented as a slide show, or printed on cards. I prefer the slide show option, not least because children usually find it interesting and fun, and, quite remarkably, frequently ask to do it ‘again’! The data collection form has space for recording stimulability data and the child’s inventory of marked consonants. In stimulability testing, the child is asked to directly imitate vowels in isolation and CVs, usually [ba bi bu] etc. focusing on vowels and diphthongs already circled on the form; and consonants of interest in CV or VC contexts, or both, but not usually in isolation. Marked consonants in the child’s inventory are circled, from a choice of /p t k f v It is usual to reassess, using the Quick Screener, with parent observation, at the beginning of each intervention block (immediately after a break from intervention), allowing parents, who are often particularly interested in the inventories and percentages, to observe and discuss any changes. Additional testing may be required; for example, the DEAP, HAPP-3 or the Locke Task might be repeated. Any decision to terminate or continue therapy is made jointly with parents (see Baker, 2010 for thoughtful discussion). Table 1.3 provides a schema within which to view three levels of intervention goal. The basic goal of PACT is to work at word level or above to encourage phonological reorganisation, thus facilitating the emergence of clear speech. This basic goal is achieved by increasing a child’s consonant, vowel, syllable-shape, syllable-stress, phonotactic and suprasegmental repertoires and accuracy; and by promoting generalisation of new segments, structures and prosodic features to increasingly challenging contexts and situations. The intermediate goal is to target groups of sounds related by an organising principle (processes, rules or patterns), addressing phonetic and perceptual levels as required. Specific intervention goals are to target a sound, sounds or syllable structures, using horizontal strategies: targeting several sounds within a sound class or manner of production, or syllable structure category, and/or targeting more than one process or deviation or structure simultaneously. Goal selection and attack strategies are primarily therapist-driven and explained to parents. Multiple goals are addressed in and across treatment sessions and within homework, sequentially and simultaneously, and rarely cyclically. For example, Emeline, 5;1, in Session 4 of her second therapy block, had three concurrent goals. First, a phonetic goal to produce /dƷ/ and /t∫/ in onset and coda in six practice words; second, a phonological goal to recognise distinctions in input, and to mark distinctions in output in short phrases between the cognate pairs /p b/, /t d/ and /k ɡ/ (e.g., with Emeline instructing and adult to ‘Touch the pea/bee’, ‘Touch the toe/doe’, ‘Touch the cap/gap’; and then switching roles); and a generalisation goal to use the voiceless fricatives /f/, /s/ and /∫/ in conversational speech in untrained words in the therapy session and during an agreed daily period at home. The materials and equipment required consist of toys, vowel and consonant pictures on cards and worksheets, a ‘speech book’ (exercise book, ring binder or scrapbook), drawing and ‘making’ materials and equipment, rewards such as stamps and stickers, a desktop, laptop or tablet computer for slide shows and the administration of the Quick Screener and an audio recorder to record therapy snippets. It is helpful but not essential for the family to have a computer and audio recorder. One option is for them to use a tablet (e.g., iPad or Android and an inexpensive voice recorder App such as iTalk Recorder Premium from Griffin Technology (http://store.griffintechnology.com/italk-premium). Pictures in speech books and on cards usually include printed captions to clarify what the target words are meant to be. Captions are printed consistent with the way in which early literacy instruction is commonly delivered, with all words printed in lower case, and capital letters used only for the beginnings of proper nouns. Suitable pictures are available to clinicians and families, at no cost, at www.speech-language-therapy.com. The clinician sees the child for 50–60 minutes (usually 50 minutes) once per week in therapy blocks. The minimum parent participation involves the parent joining the therapist and child for 20 minutes at the end of a session, or 10 minutes at the beginning and end; and the maximum parent participation sees parents staying 50–60 minutes. The parent assumes the role of a dynamic collaborator in a treatment triad with child and therapist. Segments of parent participation always require the child’s continued involvement, to properly demonstrate what should happen at home. The following is an outline of a 50-minute session for Iain, 5;7, with his father Gordon and a therapist, towards the end of his second treatment block (of three) in which one treatment target was addressed. Iain had a persistent [n] for /l/ sound replacement SIWI, and over the previous 2 weeks, had finally become stimulable for /l/ in CVs by dint of every phonetic placement technique the therapist knew—or at least it felt that way! Gordon left Iain with the therapist for 15 minutes while he dropped his wife Lucinda at a railway station and took 7-year old Bruce to school, returning for the final 35 minutes of the session with Iain’s brother Fergus, 18 months, who played happily alone while work proceeded. Iain had already engaged in items 1–3 with the therapist. Figure 9.3 /l/ versus /n/ minimal word pairs. Drawings by Helen Rippon, Speech and Language Therapist, www.blacksheeppress.co.uk A unique feature of PACT is its administration in planned blocks and breaks (Bowen & Cupples, 2004) that are intended to The initial block and break are usually about 10 weeks each, and then the number of therapy sessions per block tends to reduce while the period between blocks remains more or less constant at 10 weeks. A typical schedule is 10 weeks on, 10 weeks off, 8 weeks on, 10 weeks off, 4–6 weeks on. It is suggested to parents that, during the breaks, they do no formal practice for up to 8 weeks. In the 2 weeks prior to the next block, they are asked to enjoy looking through the speech book with the child a few times and to do any activities the child wants to do. Although they do not do homework or revision in the breaks, the child’s parents continue to provide modelling corrections, reinforcement of revisions and repairs and pursue metalinguistic activities, incidentally, as opportunities arise, using the strategies learned in ‘parent education’ in the therapy block(s). Typically those children with phonological disorder only have needed a mean of 21 consultations for their output phonology to fall within age-expectations, so many are ready for discharge at the end of their second block (about 30 weeks after initial assessment) or immediately after their second break (about 40 weeks after initial assessment). A small number of children engaged in PACT have required a third block; fewer have needed four; and there is no record of a child needing more than four treatment blocks. Children with phonological disorder as well as mild language or fluency difficulties have required about the same volume of therapy for speech, but most have continued having intervention for longer to address their other, non-speech goals. Like goal selection and attack, target selection (with exceptions like Shaun’s wanting to work on /∫/ to pronounce his own name correctly) is therapist-driven, and the reasons certain targets are given preferential treatment are explained to parents. As part of a stopping pattern, Shaun, 4;9, mentioned in Chapter 8, called himself ‘Dawn’. An adult neighbour whose name actually was Dawn, apparently oblivious to the misery it evoked and angry requests from Shaun to ‘Stop it’, teased him endlessly to the point where all he and his mother were interested in doing in therapy was to work on /∫/ in just one word – Shaun (which we did, with a successful outcome). In selecting treatment targets, the clinician uses linguistic criteria, taking into account motivational factors and attributes of the child and parents; is flexible in terms of feature contrasts; and applies evidence and clinical judgement. Traditional and newer criteria (see Table 8.1 and the discussion that follows it) may be applied to isolating optimal targets. Sometimes it is necessary to fall back on other, more traditional criteria. Take Tessa for example (Bowen, 2010). Superficially, Tessa 5;10, was a perfect candidate for a least knowledge approach using high-frequency lexical targets because she had a phonetic inventory of only 13 consonants, a PCC of 38%, and extensive homophony. Or was she? She was a fretful, diffident child with wary, apprehensive parents, ready to abandon therapy if the clinician attempted anything ‘too hard’. These three were unsuited to complex maximal oppositions or empty set feature contrasts, for which Tessa had least knowledge. They needed to ease into intervention via a gentler, albeit less potent, approach using unmarked, stimulable, inconsistently erred, early developing sounds; low-frequency words with low neighbourhood density; and minimal feature contrasts. Once they were all ready to trust the clinician’s target choices and confront more difficult tasks, Tessa took more risks, handling the challenges of multiply opposed word sets within the Multiple Exemplar Training component of PACT. PACT has five dynamic and interacting components: Parent Education (Family Education), Metalinguistic Training, Phonetic Production Training, Multiple Exemplar Training (Auditory Input and Minimal Contrasts Therapy), and Homework. The therapy involves the child, primary caregiver(s) and therapist; and sometimes significant others, including older siblings, grandparents and teachers, become involved in homework. Recognising that PACT will not suit every child or every family, we hypothesised that arming interested parents with techniques (e.g., modelling, recasting, fostering repair strategies and providing alliterative input in thematic play contexts) related to their own child’s intervention needs, and by working with them collaboratively, we would tap a unique and powerful ‘therapeutic resource’. Unique because a child (usually) only has one set of parents, and powerful because (usually) parents likely spend the most time with their child and are most motivated to help. Through supportive parent education, they would be guided to use ‘speech time’ optimally in homework and incidentally in real (not contrived) communicative contexts as natural opportunities arose. This might lead to the need for less consultation and fewer child–clinician contact hours, and ensure that planned breaks from therapy were used more productively. Incorporating simple principles of adult learning (Knowles, 1970), parents learn techniques, explained in plain-English (Bowen, 1998a, b), including: delivering modelling and recasting, encouraging self-monitoring and self-correction, using labelled praise and providing focused auditory input. Employing clinical judgement and responding to parent feedback, parent education is delivered according to need (Bowen & Cupples, 2004). It may happen in the form of modelling, counselling, direct instruction, observation, scripted routines, participation and discussion in assessment and therapy sessions, as well as role-playing, ‘coaching’ and rehearsal. For some families, this involves independent reading of handouts and publications (Bowen, 1998a, b; Flynn & Lancaster, 1996) and viewing informational slide shows that are e-mailed to them or accessed from www.speech-language-therapy.com, viewed on home computers, and later discussed. Some families need more support than this and are ‘talked through’ informational handouts and view individualised (for them and their child) slide shows in-clinic, explained carefully by the therapist. Written information is provided in a speech book that often becomes a prized possession of the child’s, particularly if it features his or her own artwork. It is used to facilitate communication between therapist, family and others involved (e.g., grandparents or teachers). It includes current targets and goals, a progress record, homework activities, developmental norms and information about intervention for SSD. Parents and teachers are encouraged to contribute to the book: recording progress, commenting on homework content and performance, noting favourite activities or their own innovations and often giving important pointers to the therapist that might otherwise be unavailable. For instance, Bowen & Cupples (2004) reported that Sophie, 4;3, with a moderate-to-severe SSD, talked constantly at home and was animated and chatty in the clinic, but that her teacher surprised (and enlightened) the therapist and her parents when she wrote in the speech book: ‘I enjoy working with Sophie and doing the activities in her book. She is very responsive in the one-on-one – loves it – but if I try to involve another child or two she clams up completely. I think you should know that she never speaks to her kindy peers – only to teachers and the aide, and only one-to-one, and in a quiet voice we can hardly hear’. The teacher’s insightful note led to providing pre-school personnel with strategies that fostered Sophie’s ability to communicate with her peers (see ‘Adult Communicative Styles and Encouraging Reticent Children to Converse’ at www.speech-language-therapy.com). Parents of the children in the efficacy study were not ‘selected’ in any sense and were not forewarned prior to initial consultation that they would be asked to participate in the therapy. Nonetheless, all the families rose to the task willingly, becoming actively involved in therapy sessions and in homework which they did in 5- to 7-minute bursts once, twice or three times daily, as recommended. On average, homework was done 24 times per week (4 families), 18 times per week (1 family), 12 times per week (7 families), 8 times per week (1 family) and 6 times per week (1 family) (Bowen, 2010; Bowen & Cupples, 2004). Parents vary in the amount and style of information they need, some performing well with little explanation, learning best via observation and rehearsal. Others want a lot of ‘training’ before being comfortable performing activities at home. Although it is encouraged without insisting, some parents are shy when it comes to rehearsing homework tasks in the clinic with the therapist watching. Educational levels appear to have little bearing on how readily parents comprehend and work with concepts, expressed in plain-English, such as ‘sound patterns’, ‘sound classes’, ‘reinforcement’, ‘modelling’, ‘labelled praise’, ‘revisions and repairs’, ‘progressive approximations’, ‘shaping’ and ‘gradualness of acquisition’. Subjectively, it seems some parents have an instinct, ‘feel’, or ‘gene’ for this sort of thing, and some appear to have missed out! Some are intuitive ‘natural teachers’, and some are not. Despite this, it is amazing what parents will learn to do well with adequate levels of support when they perceive that their child stands to benefit. Parents with personal histories of communication difficulties similar to their child’s may be endowed with a special empathy, although some of them may have residual issues affecting their capacity to reflect on language function and to enjoy language play (Crystal, 1996, 1998). In delivering parent education, it is imperative to This component was inspired by a fascinating article by Dean and Howell (1986) that proposed a role for guided discussion and meta-language in helping children reflect on the features or properties of phonemes, and the structure of syllables, with a view to improving their awareness of when and how to apply phonological repair strategies. Dean, Howell and colleagues went on to develop Metaphon, described in Chapter 4, an approach that centres on dialogue between therapist and child with only passing references to parents. We wanted to take these ideas in a new direction, actively engaging parents, still with the aim of increasing children’s metaphonological awareness, and their capacity to reflect on their own speech performance. Excited by the practical connections between Ingram’s (1976) schema of underlying representation, surface form and mapping rules, and the Dean and Howell (1986) suggestions for developing linguistic awareness, it struck us that, if they were only implemented for a short period in weekly therapy sessions, their effects might not be optimal. Our plan was to provide parents with training, scripts and informational handouts (later to become Bowen, 1998a, and in French, Bowen, 2007). We reasoned that if child, and clinician and parents, and teachers where applicable, used a common language around sound and syllable properties, and the reasons for, and the communicative consequences of homophony, it would improve the accuracy of that child’s knowledge of the system of phonemic contrasts and increase the likelihood of spontaneous self-corrections. This would be especially the case if all the adults involved (not just the SLP/SLT) knew how to reinforce them. Metalinguistic training fosters ‘phonological discoveries’ by the child. His or her capacity to perceive, talk about, reflect upon and revise and repair homophonous productions is enhanced via simple routines and systematic feedback delivered by parents. Using guided discussion (Dean & Howell, 1986), child, parents and clinician talk and think about the properties of the speech sound system and how it is organised to convey meaning, incorporating simple metaphonological and phonological awareness (Hesketh, A28) activities. In finding a common language to describe phonemic features and syllable shapes, the clinician can borrow from many sources, including Klein’s (1996a, b) ‘imagery terms’ or ‘imagery labels’ (e.g., poppy, windy, throatie and tippy, discussed in Chapter 4); the Metaphon (Dean et al., 1990) terms such as long, short, front, back, noisy, growly, whisper and quiet; and the imagery names and cues in Table 6.5. Activities, at home and in therapy, involve sound picture associations (e.g., /.ɹ/ is a roaring lion sound; /t∫/ is a choo-choo train; /f/ is a bunny rabbit sound, because it is made with teeth like a bunny); phoneme segmentation for onset matching (e.g., kangaroo starts with /kə/, or for preference, /k/); awareness of rhymes and sound patterns (e.g., games with minimal pairs like tie-die; and near minimal pairs like tie-tight); rudimentary knowledge of the concept of ‘word’; understanding the idea of words and longer utterances ‘making sense’; awareness of the use of revision and repair strategies using ‘judgement of correctness’ games (e.g., The boy tore his shirt vs. The boy tore his cert) and the ‘fixed-up-one routine’; and playing with morphophonological structures to produce lexical and grammatical innovations (e.g., pick vs. picks). The use of spontaneous revisions and repairs is fostered, particularly at home, by use of the fixed-up-one routine. The routine is a metalinguistic technique that allows adults to talk simply to children about revisions and repairs (or self-corrections). Scripts, such as the one displayed in Figure 9.4, are provided to introduce them to the technique, and various versions of it are available, with an instructional slide show at www.speech-language-therapy.com. Also with regard to self-monitoring and making revisions and repairs, the child is encouraged to notice phoneme collapses or homonymy (e.g., boo and blue realised homophonously as /bu/). Figure 9.4 An example of a fixed-up-one routing. Drawing by Helen Rippon, Speech and Language Therapist: www.blacksheeppress.co.uk. The 1986 suggestions of Dean and Howell were adopted and extended, allowing metalinguistic awareness to be targeted in naturalistic, supportive clinic and home settings. Expressions that crop up constantly in the context of PACT being discussed with parents are ‘talking task’, ‘listening task’, ‘thinking task’, ‘fixed-up-ones’, ‘word’, ‘rhyme’, ‘making sense’, ‘make the words sound different from each other’, ‘two-step word’ and ‘remember the 50:50 split’. The latter refers to the general recommendation that the 50:50 split between ‘talking tasks’ versus ‘thinking and listening tasks’ that is observed in therapy sessions is also observed at home. Sometimes a family will generate its own appropriate terminology, and memorable offerings have included ‘Bob’, ‘Bobs’ and ‘fix-its’ in relation to ‘fixed-up-ones’ (Bob the Builder’s motto is ‘Can we fix it? Yes we can’) and ‘Einstein Time’ in relation to listening and thinking tasks! ‘Einstein Time’ and ‘Nice one, Einstein!’ were the brainchild of Sebastian’s father, who was intrigued by my framed picture of Einstein, adorned with a thinks bubble that read ‘THINKING’. The picture is sometimes put on the table during ‘thinking tasks’, such as judgement of correctness games, silent sorting of word-pairs, ‘point to the one I say’ activities, and word classification games, to cue everyone that (quiet) ‘thinking’ is supposed to be happening! Readers who would like to experiment with this idea can download Einstein pictures from www.speech-language-therapy.com.

Parents and children together in phonological intervention

Primary population

Why 3- to 6-year olds?

Secondary populations

Theoretical basis

Empirical support

Assessment

Quick Screener

s z ∫ Ʒ ʧ ʤ/. The stimulability and markedness data are later used in the decision-making process for treatment target selection, as outlined in Chapter 8.

s z ∫ Ʒ ʧ ʤ/. The stimulability and markedness data are later used in the decision-making process for treatment target selection, as outlined in Chapter 8.

Assessing progress

Goals and goal attack

Materials and equipment

Intervention

Therapy sessions

Intervention scheduling

Dosage

Target selection

PACT components

Parent education (Family education)

Rationale

Methods

Discussion

Metalinguistic training

Rationale

Methods

Discussion

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree