Paediatric history-taking is vital because it usually holds the key to the diagnosis.

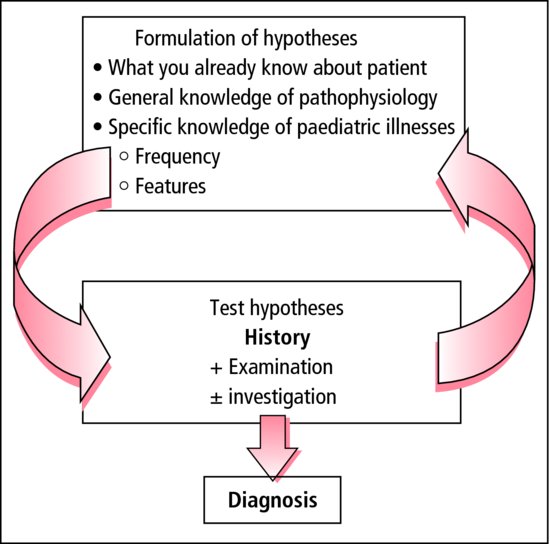

Paediatric history-taking is vital because it usually holds the key to the diagnosis.Diagnosis involves a recurring cycle where you formulate and test hypotheses. As you collect more information about the patient, you will reject some diagnoses, and come up with alternatives that were not on your original list (Figure 2.1). When you first begin paediatrics, it is useful to work through a list of standard questions. Once you are familiar with these, aim to move towards problem-orientated histories: generate mental lists of differentials for common presenting symptoms and then focus your history around these. This thoughtful, logical approach is much better than blindly asking a series of questions that you have learned by rote.

Figure 2.1 Reaching a diagnosis. It is important to start with a reasonable differential diagnosis (your hypotheses). The ‘Paediatric symptom sorter’ in this book can help. The history contributes much more than examination or investigations.

- Perinatal and birth

- Development

- Immunization

- Family and social history emphasis

2.1.1 Parents

Throughout most of childhood, parents act as the child’s advocate and interpreter. Parents tell us about the child’s symptoms – although the children contribute more and more as they grow older. Parents put into effect any treatments needed outside hospital.

Small children only survive because their parents are concerned about them. A few are less concerned than they should be, and their children suffer from neglect. Others are more than usually concerned. Do not regard overanxious parents as a nuisance. Instead, view their genuine concern for their child positively, and help them cope with their anxieties through patient reassurance. Parents’ behaviour often reflects their own upbringing, as do excessive concerns with physiological functions, such as eating, sleeping and bowel habits.

Some parents seem easy to interview, and others difficult. If you are tempted to label someone a ‘bad historian’, remember that a historian is the person who collects and records the history!

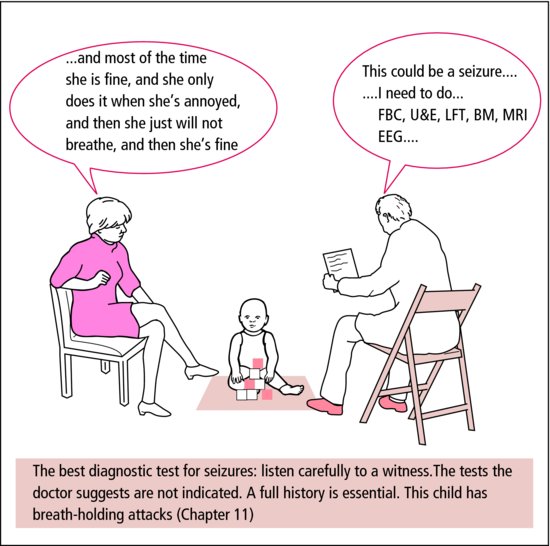

Try to disentangle the facts from the parents’ interpretation. Ask ‘What exactly did you see that made you think that?’ rather than accepting interpretations at face value (Table 2.1).

Table 2.1 Fact and interpretation in history and examination.

| Fact | Interpretation |

| She cries and draws her legs up to her tummy | Our baby has colic |

| He has watery stools 6 times a day, whereas his normal stool is formed and once daily | He has bad diarrhoea |

| She gets wheezy when she runs | She has asthma |

| He falls asleep at school | He is lazy at school |

2.1.2 Involving the child

Children from about 2 years can hear, understand and say a lot. By 7 or 8 years, they are wise. Do not talk about them as if they had no understanding – and you may have to discourage parents from doing the same. Sometimes, if both are agreeable, it is useful to talk to the parent(s) and the child privately to allow them to express concerns, or to give particular advice. Older teenagers may prefer to be seen on their own first. Whatever the medical problem, the child is first a child. Not ‘he is a diabetic’ or ‘she is an epileptic’: he has diabetes, she has epilepsy.

2.1.3 History-taking

The child’s history covers the same ground as that of an adult patient, with some important additions.

2.1.3.1 Approach

- Address the parents by name, not as ‘mum’ or ‘dad’.

- Find out what the child is called at home and use that name.

- Begin your notes with the name, sex and the age in years and months – accurate age is essential and often defines the differential diagnosis.

- Note the name of the school, nursery, clinic or health centre she attends.

- Consider the child during the history:

- A young child may be happiest on a parent’s knee.

- A more independent one may prefer playing with toys, which should be available.

- An older child must be fully included in the discussion.

- A young child may be happiest on a parent’s knee.

- Arrange the furniture to encourage a sense of partnership between parents and doctor and avoid confrontation over the top of a desk.

- Birth history

- Where

- Delivery

- Gestation

- Weight

- Ante/postnatal problems

- Neonatal problems (jaundice, SCBU, ventilation, antibiotics)

- Maternal health

- Illnesses, operations and accidents

- Feeding – neonatal, weaning, concerns about growth

- Immunizations

- Development

- Mother – name/age/occupation/health

- Father – name/age/occupation/health

- Siblings – name/age/health

- Inherited or genetic conditions

- Contact with common infections

- Nursery/school

- Pets

- Housing.

PRACTICE POINT

PRACTICE POINT2.1.3.2 History of the presenting condition

Begin with this because it is what they have come to tell you about. Let them tell it their own way first; then ask specific questions to fill in necessary details (Figure 2.2). Frequent interruptions or insistence on ordered chronology inhibit free speech.

Ask about patterns of eating, sleeping and activity. If these have not changed, serious illness is unlikely. A reduction in appetite or activity, or an increased need for sleep, are likely to be significant. Recorded weight loss is always important.

PRACTICE POINT

PRACTICE POINT- Start with OPEN questions: How is she? Why are you worried?

- Add CLOSED questions: How often does he wheeze? Which inhaler do you use most?

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree