99 Parasitic Infections

Parasitic disease causes extensive morbidity and mortality worldwide in children, particularly Plasmodium falciparum, which causes 1 to 2.7 million deaths annually. The morbidity of parasitic disease disproportionately affects the developing world with an estimated 39 million disability-adjusted life years attributable to infections with parasitic worms. Children in the United States are still at risk for parasitic infection. More common infections include giardiasis, pinworm infections, and head lice. Contaminated water and pets can serve as exposures to particular parasites including Giardia lamblia, Cryptosporidium parvum, Toxoplasma gondii, and Toxocara canis. Although covered in Chapter 89, it should be kept in mind that infection with Trichomonas spp. is the most common parasitic infection in the United States with 7.4 million infections each year. A comprehensive review of all parasitic infections in children would exceed the scope of the chapter, so an overview discussion of the most common intestinal parasites, systemic parasites, and specific coverage of malaria is presented.

Intestinal Parasites

Etiology and Pathogenesis

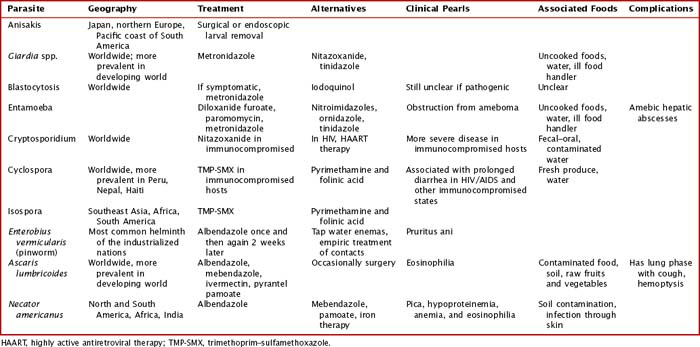

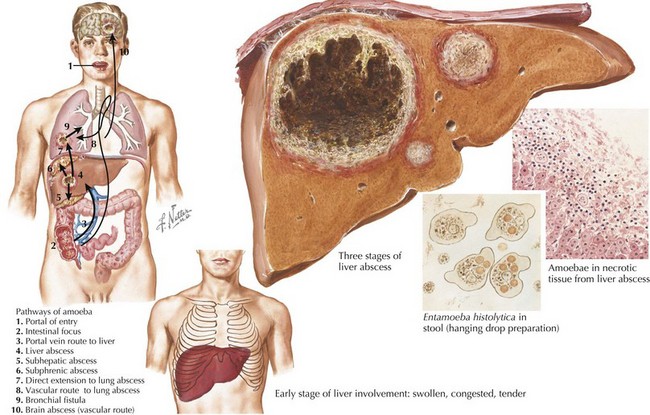

Intestinal parasites infect millions worldwide, particularly in developing countries with poor access to potable water and in patients with comorbidities. Intestinal parasites that are the most common in children in the United States include: G. lamblia, Entamoeba histolytica, and C. parvum. Table 99-1 reviews additional causes of intestinal parasitic infections (Figures 99-1 and 99-2).

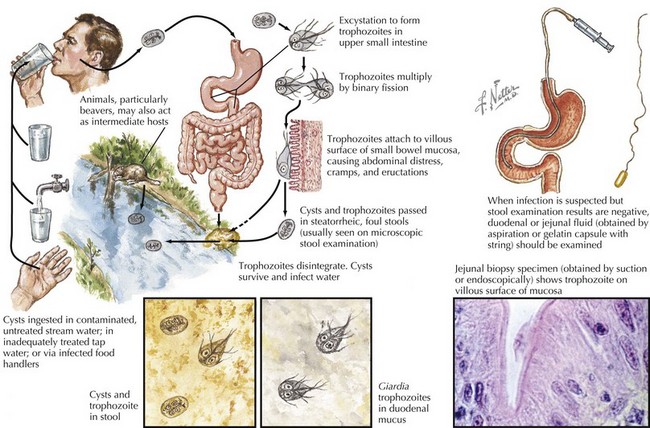

G. lamblia is a flagellated protozoon and the most common cause of parasitic enteritis in the United States. Outbreaks can occur from contaminated water supplies, including pools, because it is resistant to chlorination as well as person to person in daycare centers. The mode of transmission is often fecal–oral or direct person-to-person contact (Figure 99-3).

Clinical Presentation

Intestinal infection with parasites is often initially asymptomatic in a carrier state. Children with intestinal parasites can present with failure to thrive, diarrhea, abdominal pain, a protuberant abdomen, anemia, blood in the stool, and delayed development. A careful history with particular attention to travel and food and water intake is valuable. Additional details about sources and geography can be found in Table 99-1

Extraintestinal Parasites

Etiology and Pathogenesis

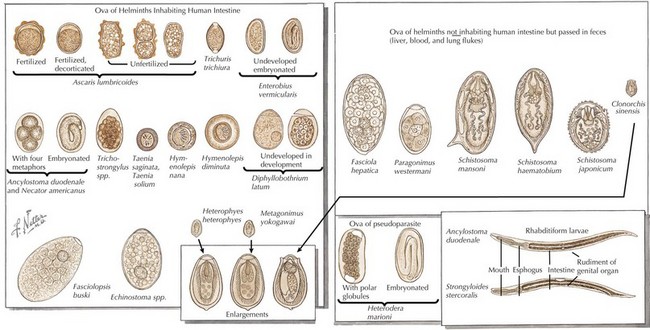

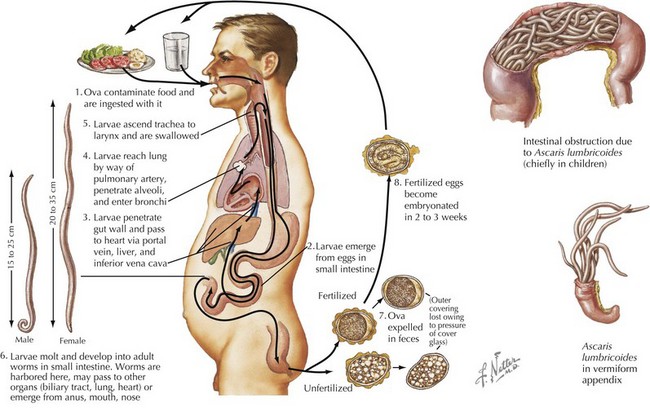

Systemic helminth infections, including Strongyloides stercoralis, Trichinella spiralis, Ascaris lumbricoides, Toxocara canis, and Trichuris trichiura, are spread via fecal contamination with worms penetrating into the toes of barefoot humans or through ingestion of cysts (Figure 99-4). Discussion of individual parasites is included in Table 99-2.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree