31 Pain Assessment and Management

The goals of this chapter are to describe the role of the interdisciplinary team (IDT), the importance of quality improvement, the epidemiology of pain in children with life-limiting illnesses, pain assessment and measurement, the myths surrounding pain management, and pain management guidelines. The reader is referred to other references for more detailed discussion of pediatric analgesic pharmacology.2,3

Pain Management, The Interdisciplinary Team, and The Child with a Life-Threatening Illness

The World Health Organization (WHO) mandates that a certain standard of pain management be available to every child receiving palliative care irrespective of location.4 As an extension of the WHO document, individual countries and groups of countries are declaring standards of pain management related to pediatric palliative care. Quality of life is often related to a child’s experience of pain and is therefore vital that the child receive excellent pain assessment and management. Successful pain management often needs the combined efforts of an IDT within the palliative care team of the medical, nursing, social work, play therapy, physiotherapy, occupational therapy disciplines, among others.

The Interdisciplinary Team and the Alleviation of Suffering

Support for parents includes education about anticipated potential symptoms. Knowledge will increase a sense of control. This in turn lessens anxiety and this may positively affect the child’s pain experience. Competent and compassionate care can alleviate a child’s pain and suffering. This can be achieved through a trusting, consistent, and honest relationship among all involved in providing care, and the family and the child. Because children are especially vulnerable and depend on adults to act as their advocates we must support the humane and competent treatment of pain and suffering at all times (Table 31-1).

TABLE 31-1 Clinical Background and Responsibilities in Pediatric Pain Management for Children Receiving Palliative Care

| Professional background | Contribution toward pain management |

|---|---|

| Pediatric palliative care physician | Primarily responsible for the assessment, diagnosis, and management of physical pain, including the prescription of pharmacologic, and non-pharmacologic management. May have a role in the alleviation of the psychological and existential components of pain. |

| Pediatric palliative care nurse | Primarily responsible for implementing and monitoring pain management through ongoing assessment and measurement. Also has a role in advocating for the child’s pain management and a role in the alleviation of the psychological and existential components of pain. |

| Pediatric palliative care social worker | Primarily responsible for the social domain of care of the child and family, especially when affecting pain management. Has a major role advocating for the child and family, including pain management. |

| Pediatric palliative care child-life therapist | Primarily responsible for the use of play as a therapeutic means of self-expression. This may include the expression of pain severity and suffering through therapeutic play. |

| Pediatric palliative care spiritual care provider | Primarily responsible for assessing and managing the spiritual components of patient receiving palliative care and the existential suffering related to dying. Suffering related to the spirit may be related to the experience of physical pain. |

Epidemiology of Pain in Children with Life-Threatening Illnesses

Pain and other symptoms at the end of a child’s life

Pain and other physical and psychological symptoms are highly prevalent in children at the end of life. The proxy report of nurses documented the symptoms of dying children, using a modified Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale.5 A mean of 11.1 ± 5.6 symptoms was documented per child. At least half of the children had six symptoms; the most frequent ones being lack of energy, pain, drowsiness, skin changes, irritability, and extremity swelling. Lack of energy was the most distressing symptom for nearly one-third of the children. Nervousness, worry, and dysesthetic extremities were notably distressing, although not frequent. Most children were described in the health professionals’ notes as being “always comfortable” to “usually comfortable” in the last week (64%), day (76.6%), and hour (93.4%) of life. A retrospective chart review documented the signs and symptoms occurring at the end of life in 28 children dying from cancer in Japan. All children experienced anorexia, 82.1% had dyspnea, and 75% had pain. Other symptoms included fatigue (71.4%), nausea and/or vomiting (57.1%), constipation (46.4%), and diarrhea (21.4%).6 This symptom profile parallels that of the North American reviews of the symptoms of dying children.7–9

Pain syndromes related to tumors in children with cancer

Despite the predominance of treatment-related pain, a number of children have pain related to a tumor, despite the initial response of their pain to treatment. One-third of the pain experienced by patients in the hospital setting was tumor-related pain, but less than 20% of the pain experienced by outpatients was caused by tumor.10 Direct tumor involvement of bone, hollow viscera, or nerves are more common causes of pain in adult patients with cancer than in children. Such tumor involvement commonly results in somatic, visceral, and neuropathic pain, respectively. Somatic pain is typically well-localized and is frequently described as aching or gnawing. Examples of somatic pain include pain associated with primary or metastatic bone disease or postsurgical incision pain. Visceral pain results from the infiltration, compression, distension, or stretching of thoracic and abdominal viscera by primary or metastatic tumor. This pain is poorly localized, often described as deep squeezing and pressure and may be associated with nausea, vomiting, and diaphoresis, particularly when acute. An example of visceral pain includes pain associated with tumor of the liver, either primary such as hepatoblastoma, or metastatic, such as neuroblastoma. Neuropathic pain most commonly results from tumor compression or infiltration of peripheral nerves or the spinal cord. Chemical- or radiation-induced injury also may result in this sort of pain. The clinical features of pain resulting from neural injury include:

The pattern of symptoms, based on the self-reports of children aged 10 to 18 treated for cancer, was studied.11 Children were surveyed across the spectrum of illness and included newly diagnosed patients, those receiving a bone marrow transplant, and those receiving palliative care. It showed that children with cancer are very symptomatic and are often highly distressed by their symptoms. A prevalence rate greater than 35% was noted for the symptoms of pain, drowsiness, nausea, cough, anorexia, lack of energy, and psychological symptoms. In-patients reported being more symptomatic than their out-patient cohorts. Children with solid tumors were more symptomatic than children with other malignancies. Pain, nausea, and anorexia were clustered as being highly distressing symptoms.11 Children 7 to 12 years of age, also treated for cancer, similarly self-reported their symptoms. The most prevalent symptoms were pain, difficulty sleeping, itch, nausea, fatigue, and anorexia.12

Pain in children with cystic fibrosis at the end of life

A retrospective chart review at a tertiary-care hospital summarized the end-of-life care of patients more than 5 years of age and dying from cystic fibrosis in the United States.13 Increasing pain for this patient population may signal advanced, progressive disease.14 Twenty-five percent of these patients had been receiving opioids for the treatment of chronic headache and/or chest pain for more than their last 3 months of life. When opioids were used for the treatment of breathlessness and/or chest pain, the proportion increased to 86%. Chest, head, extremity, abdomen, and back pain were the most common pain locations during end-of-life care.14

Pain and other symptoms in children with neurodegenerative illnesses

Pain, breathlessness, and oral symptoms such as secretions were highlighted as the most common symptoms by caregivers proxy reports for children in the last month of life at an in-patient hospice.15 Half of the children were non-communicative. Neurodegenerative illness was the major diagnostic category in this in-patient hospice population. Common sources of pain in children with cognitive and physical impairment include muscle spasticity and problems of the musculoskeletal system, such as hip dislocation or kyphoscoliosis.

Pain and other symptoms in children with HIV/AIDS

HIV/AIDS is known to cause pain and other symptoms for multiple reasons, including primary treatments, associated infections, and other complications.16 Possible causes of pain include bowel dysfunction, cachexia, pancreatitis and sequelae of infection. In a U.S,-based study, 59% of HIV-infected children reported that their pain impacted negatively on their lives.17

Pathophysiology of Tumor-Related Pain in Childhood Cancer

Mechanisms for persistent neuropathic pain after damage to peripheral tissues include:

Pain Assessment in Children with Life-Threatening Illnesses

The pain assessment of the child receiving palliative care may be a complex process. Regular pain assessment of the child receiving post-operative pain management is standard practice at most children’s healthcare facilities. It is a less-established practice that the child with progressive illness receives a regular pain assessment. Pain may still not be thought of or asked about when the child’s condition is rare, poorly understood, and/or impairs cognition; and clinicians may erroneously believe that if patients do not volunteer information about pain, then it is not a relevant clinical issue.18 In addition, children and their caregivers may not volunteer information about pain due to a fear that it may indicate progressive disease. Continually assessing a child’s pain is an essential component of competent pain management in pediatric palliative care.

Pain measurement as part of pain assessment

Unidimensional Self-Report Measures

Self-report measures of pain in children have largely focused on the assessment of acute pain severity. Generally the data support the use of visual analogue scales (VAS) or faces scales for children over the age of 5.19 VAS have been used in the assessment of pediatric cancer pain; frequently they have anchors of no pain and the worst pain possible. To use such scales, children must understand proportionality, to be able to conceptualize their pain experience along a continuum and be able to translate that understanding to the visual representations on the line and the anchors (Fig. 31-1).

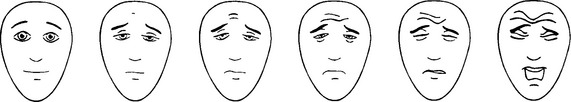

Fig. 31-1 Visual Scale for Assessment of Pediatric Pain.

(Hicks CL, von Baeyer CL, Spafford P, van Korlaar I, Goodenough B. Faces Pain Scale-Revised: Toward a Common Metric in Pediatric Pain Measurement. Pain 2001; 93:173-183. With the instructions and translations as found on the website: www.painsourcebook.ca. This figure has been reproduced with permission of the International Association for the Study of Pain® [IASP®].)

Similar strategies, such as Likert scales with anchor points of 1, no pain, and 5, extreme pain, have been used to assess pain in children with cancer.20 However, research on the use of verbal rating scales with children 9 years and older has not clearly established the utility of this approach over visual analog scales.21 Other investigators have used visual cues, such as different pictures of a child’s face that are graded from neutral or happy expressions for no pain to sad or distressed expressions for extreme pain.22,23

Behavioral Observation Measures

The subjective distress of acute pain, particularly after traumatic medical procedures, often manifests itself in certain facial expressions, verbal, and motor responses. Behavioral methods for assessing pain in children require independent raters recording the physical behaviors of children in pain, as well as the frequency of the occurrence.24 Behavioral measures of pain in children consist of observation checklists in which a trained observer records the occurrence of certain behaviors. The frequency and duration of the behaviors that occur during the medical procedures are scored to produce a numerical value that represents the child’s overall distress. This value is an integrated index of a child’s anxiety, fear, distress, and pain, but children’s behavioral scores have been interpreted as their global pain scores.25

The Gauvain-Piquard rating scale26 is an observation scale designed to assess chronic pain in pediatric oncology patients aged 2 to 6 years. The lack of operational definitions and the low kappa coefficients question the utility of this scale. The scale consists of 17 items:

Pain Measurement in Children with Neurocognitive Impairment

A substantial number of children who die have an illness that results in cognitive impairment. Many neurodegenerative diseases impact profoundly on the child’s ability to verbally communicate. The physical aspects of certain illnesses, such as grimacing or hypertonia, can mimic features or behaviors commonly attributed to pain. In one post-operative pain study, 24 children aged 3 to 19 years with cognitive impairment were rated by their caregivers and researchers as to their perceived intensity of the child’s pain pre- and post-surgery.27 Familiarity with an individual child was not necessary for observers to have congruent pain measurements. Pain cues reported by 29 caregivers of non-communicative children aged 2 to 12 years with life-threatening conditions were compared against a checklist of 203 items. This study yielded a common core set of six pain cues. These are screaming and/or yelling, crying, distressed facial expression, tense body, difficult to comfort, and flinching when touched.28

MultiDimensional Symptom Assessment Scales

The Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale 10-18, modified from an adult version, was developed for children aged 10 to 18 years with cancer. In a mean of 11 minutes, the majority of children were able to answer questions about how severe, frequent, and distressing they found their symptoms.11 For the younger child with cancer, the scale was modified and trialed in 7 to 12 year olds.12 On this scale, pain is one of many symptoms assessed in 3 dimensions: severity, frequency, and distress.

Adequate Pain Management at the End of Life is Achievable

Goals for pain management

The goals for pain management for the child receiving palliative care are:

Pain relief with what would be considered conventional analgesic doses and routes is achievable to fulfill these goals for the vast majority of children facing pain as a consequence of advanced illness. This was well documented in a 1995 study of a pediatric oncology population, where the records of 199 children and young adults dying of malignancy were reviewed. Only 6% of these patients required what would be considered massive doses of an opioid infusion, defined as 100-fold the usual post-operative opioid requirement.29 Of that small proportion of patients, there were a few instances where extraordinary doses of analgesia, the use of unusual routes such as opioid infusions given via the subarachnoid route, or the provision of sedation was required to ensure comfort at end of life.29 Similarly, regional anesthetic techniques are infrequent in treating pain at end of life for children with cancer diagnoses.30 A review conducted over a 5-year period assessed the opioid doses used in children (n = 42) dying at a pediatric hospice. The parental morphine equivalents ranged from 0.001-73.9 mg/kg/hr, with a median of 0.085 mg/kg/hr.31

Myths and misperceptions about pain in children

The myth that children either do not experience pain, or do not experience pain as much as adults, has until recently inhibited progress in pain management for children. Since the 1980s there has been a growing movement toward improved pain control for infants, children, and adolescents. This movement was partly a response to the weight of evidence indicating that poor pain control negatively influenced outcome in post-operative neonates.32 It was also partly due to improved measures of pain severity in infants and children and a critical mass of clinicians with developing expertise in this area. This latter has seen the development of interdisciplinary pain services in many pediatric centers around the world. In most cases centers have a close professional affiliation with pediatric palliative care services.

Addiction is a psychological and behavioral syndrome characterized by drug craving and aberrant drug use. Some parents fear that exposure to an opioid will result in their child subsequently becoming a drug addict. The incidence of opioid addiction was examined prospectively in 12,000 hospitalized adult patients who received at least one dose of a strong opioid.33 There were only four documented cases of subsequent addiction in patients who did not have a history of drug abuse. These data suggest that iatrogenic opioid addiction is an uncommon problem in adults. This observation is also consistent with a large worldwide experience with opioid treatment of cancer pain in childhood.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree