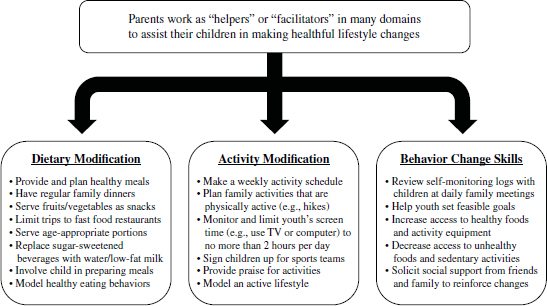

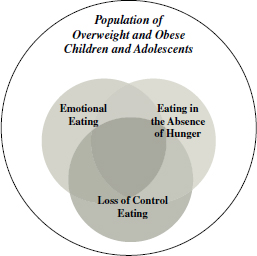

Chapter 22 Anna Vannucci and Marian Tanofsky-Kraff Obesity among children and adolescents is a pressing public health concern. Rates of pediatric obesity saw staggering increases over the past several decades. Although the overall prevalence of obesity appears to have stabilized in recent years, it remains high. Estimates from 2009 to 2010 indicate that more than one third of children and adolescents in the United States are overweight (body mass index [BMI] ≥ 85th percentile for age and sex) or obese (BMI ≥ 95th percentile) (Ogden, Carroll, Kit, & Flegal, 2012). Of serious concern, rates of extreme obesity (BMI ≥ 99th percentile) are increasing disproportionately faster than the rates of moderate levels of obesity (BMI between the 95th and 98th percentiles) (Koebnick et al., 2010). Obesity in youth has been linked to numerous medical conditions. Pediatric obesity is not only associated with cardiovascular disease risk factors such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, carotid artery atherosclerosis, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes (Freedman, Dietz, Srinivasan, & Berenson, 2009; Rosenbloom, Joe, Young, & Winter, 1999; Weiss et al., 2004), but it is also predictive of coronary artery disease and early death during adulthood (Baker, Olsen, & Sorensen, 2007; Franks et al., 2010). Orthopedic problems, asthma, and allergies are more common in obese youths as compared to their nonobese peers (Halfon, Larson, & Slusser, 2013). Pediatric obesity also is associated with a poor health-related quality of life (Fallon et al., 2005; Schwimmer, Burwinkle, & Varni, 2003; Tsiros et al., 2009). In addition to adverse medical sequelae, pediatric obesity has detrimental effects on psychosocial functioning. Overweight and obese children and adolescents are more likely than nonoverweight children to report symptoms of depression, anxiety, disordered eating, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (Kalarchian & Marcus, 2012). Obese youth frequently have a negative body image and low self-esteem (Puder & Munsch, 2010). These emotional issues may be linked to the social problems reported by this vulnerable population, including stigmatization, social discrimination and exclusion, and teasing and bullying (Gundersen, Mahatmya, Garasky, & Lohman, 2011). This chapter puts forth the rationale for the early identification of and intervention regarding eating- and weight-related problems in youth and reviews the current evidence-based guidelines for the screening and treatment of pediatric overweight and obesity. This review summarizes the key components of family-based behavioral interventions, a treatment modality that has the greatest evidence base, as well as the role of parental involvement. In addition, we describe common adaptations of family-based behavioral interventions. Novel targeted interventions that address aberrant eating patterns associated with childhood overweight and are currently under development are discussed. Common measures of treatment outcome are reviewed. Finally, clinical cases are reviewed that highlight the heterogeneity of youth presenting with weight problems and the distinct intervention recommendations. Despite the sobering statistics linking pediatric obesity to numerous medical and psychological problems, prospective data indicate that the pediatric obesity-related consequences can be prevented or potentially reversed. One study following individuals for 23 years found that obese children who developed into nonobese adults had a similar cardiovascular profile to adults who were never obese (Juonala et al., 2011). Weight reduction has also been associated with improvements in socio-emotional outcomes among youth (Lloyd-Richardson et al., 2012). However, the reality is that pediatric obesity does not spontaneously resolve with age, as childhood overweight is a robust predictor of obesity during adolescence and young adulthood (Nader et al., 2006). The tendency for obesity to track across the life span starts as early as 6 months of age (Taveras et al., 2009), which underscores the need for early identification and intervention of pediatric weight problems. Childhood is an ideal point of behavioral intervention for four reasons. This section reviews the current evidence-based guidelines for the screening and treatment of pediatric overweight and obesity and the key components of family-based behavioral interventions, which have the greatest evidence base for improvements in weight outcomes. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (Barton, 2010) and the American Academy of Pediatrics (Barlow, 2007) have published expert guidelines for the screening, prevention, and treatment of pediatric obesity. The importance of identifying at-risk youth as early as possible is stressed so that targeted interventions may be explored before more costly, intensive treatments are needed (Barlow, 2007). It is recommended that primary care and child health providers track BMI percentiles (Barton, 2010) and assess children’s medical and behavioral risk factors for obesity (Barlow, 2007). The American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines encourage providers to deliver obesity prevention messages to all youth (i.e., guidelines for fruit and vegetable intake and daily activity) and to provide specific behavior change targets for families with overweight children (Barlow, 2007). Finally, providers should establish procedures for making referrals to community resources that can provide the treatment appropriate for children’s level of adiposity and risk factors (Barlow, 2007; Barton, 2010). The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends that overweight and obese children receive specialty treatment of moderate to high intensity that incorporates behavioral counseling targeting diet and physical activity (Barton, 2010). Many pediatric obesity interventions use a “lifestyle change” approach, which refers to the notion that weight-related behaviors should be modified in a manner that is compatible with daily living so that healthful changes may be more sustainable over time (Wilfley, Vannucci, et al., 2010). According to Task Force recommendations (Barton, 2010), parents are expected to play a pivotal role in treatment. Family-based behavioral weight loss treatment is one example of a lifestyle intervention, and it is currently considered the first line of treatment for pediatric overweight and obesity (Wilfley, Vannucci, et al., 2010). There is also evidence that preventive interventions targeting modifiable risk factors, such as disordered eating patterns, may be effective (Tanofsky-Kraff, 2012). The use of pharmacotherapy or surgical options is recommended for older children and adolescents with extreme obesity and severe medical comorbidities (Barlow, 2007). Although orlistat, roux-en-Y gastric bypass, and laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding have demonstrated efficacy for the reduction of BMI in severely obese adolescents (de la Cruz-Muñoz et al., 2010; Viner, Hsia, Tomsic, & Wong, 2010; Widhalm et al., 2011), there are high rates of side effects and complications and cogent concerns about strict adherence to dietary regimens and the continued cost of medical management. It must be emphasized that pharmacologic and surgical options should be considered only if good adherence to an intensive lifestyle intervention for 3 to 6 months was ineffective at reducing weight or improving medical comorbidities (Barlow, 2007). The implementation of intensive behavioral lifestyle interventions and targeted interventions for obesity risk factors is still indicated alongside the use of pharmacotherapy and surgical options. Family-based behavioral interventions are often considered the first line of treatment for pediatric overweight and obesity due to their demonstrated efficacy in reducing adiposity (Wilfley, Vannucci, et al., 2010). The most efficacious family-based interventions incorporate these components: dietary modification, changes in energy expenditure, behavior change techniques, and parental involvement across all levels of change. Treatment is time-limited in scope; weekly sessions are comprised of separate parent and child groups as well as brief individual family meetings, which occur for 4 to 6 months with trained leaders. The general aim of dietary modification strategies is to induce an overall negative energy balance, as obese children consume greater overall calories and have a higher fat intake than nonobese youth (Davis et al., 2007). The most widely studied dietary modification approach to achieve such a caloric deficit is the Traffic Light Diet (Epstein & Squires, 1988), which classifies foods into three categories: red (low in nutrients, high in calories), yellow (high in nutrients and calories), and green (high in nutrients, low in calories). Families are taught that “red” foods signal “stop”; any foods containing 5 grams or more of fat per serving, sugary cereals, and fast food items should be eaten sparingly and limited to no more than 10 to 15 servings per week (Epstein, Paluch, Beecher, & Roemmich, 2008). Decreases in specific “red” foods known to be associated with excess weight gain—sugar-sweetened beverages and unhealthy snacks, such as fried potato chips—are also recommended (Davis et al., 2007). Families learn that “green” foods signal “go,” and increased consumption of fruits and vegetables is often targeted (five servings daily are recommended) (Epstein, Paluch, et al., 2008). “Yellow” foods are items that are highly nutritious, contain “good” fats, or have high fiber but are also high in calories, such as fish or raisins. Families are not discouraged from consuming “yellow” foods but learn to eat them in moderation. In addition to modifying the types of foods consumed, limiting portion sizes to age-appropriate standards is also crucial (Orlet Fisher, Rolls, & Birch, 2003). These strategies—when tested independently and in combination—have been shown to reduce energy intake and adiposity in children and adolescents (Wilfley, Vannucci, et al., 2010). Changes in activity patterns are critical to induce an overall caloric deficit needed for sustained weight management success. Children are encouraged to work toward engaging in approximately 60 minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity every day, and engagement in muscle- and bone-strengthening exercises, which includes activities involving jumping or climbing, is recommended to prevent a loss of muscle mass during weight loss efforts (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2008). Parents are encouraged to find activities that their children enjoy, are age appropriate, and offer variety. Inactive children should gradually increase their level of exercise and be monitored closely to prevent injuries. Evidence suggests that increasing lifestyle activity (e.g., taking the stairs instead of the elevator) is effective for sustaining weight loss (Davis et al., 2007). Decreasing the time that children and adolescents spend engaging in sedentary behaviors—those that burn a minimal number of calories, such as television watching and computer time—to no more than 2 hours per day also has a potent impact on weight loss efforts (Epstein, Paluch, Gordy, & Dom, 2000; Epstein, Roemmich, et al., 2008). Notably, reductions in sedentary behaviors have been associated with less overall energy intake (Coon, Goldberg, & Rogers, 2001), since many children snack while watching television. Interventions that incorporate behavior change strategies are more effective at achieving weight loss and the prevention of excess weight gain in youth than approaches that offer primarily psychoeducation (Wilfley, Tibbs, et al., 2007). Working with families to set feasible, specific goals is central to being successful in making behavior changes (Wilfley, Kass, & Kolko, 2011). Goals should be determined collaboratively between families and providers, and they should change gradually throughout treatment to accommodate for progress in children’s eating and activity behaviors. Parents and children are also taught to engage in regular self-monitoring, a practice that is a strong predictor of long-term weight loss maintenance (Theim et al., 2012). Families learn to pay close attention to their daily dietary and activity behaviors and to record their patterns in a log. Through weekly weight monitoring, children learn the association between their energy balance behaviors and changes in their weight (Wilfley, Vannucci, et al., 2010). It is also helpful to set up a family-based reward system to reinforce behavior changes; families develop a list of acceptable rewards or privileges, and parents provide contingent rewards to their children for achieving behavioral goals (Epstein, Paluch, Kilanowski, & Raynor, 2004). It is strongly recommended that food not be used as a reward, as it can promote overeating in a subset of vulnerable youth. Stimulus control—defined as restructuring the environment to increase desired behaviors—within the home setting also supports healthful behavior change (Epstein et al., 2004). The inclusion of parents in lifestyle interventions is critical for successful child weight outcomes. Greater degree of parental involvement in behavioral weight loss treatment leads to greater child weight loss and maintenance outcomes (Heinberg et al., 2010; Wadden, Butryn, & Byrne, 2004). Parents are actively involved at all stages of family-based behavioral lifestyle interventions (see Figure 22.1). Parents play a crucial role as key agents of change in a child’s daily life (Wilfley, Vannucci, et al., 2010). Therefore, parents most often are conceptualized in a “facilitator” role. They are taught to encourage their children in making healthy choices and to create “healthy eating and activity zones” by modifying the shared home environment. Parents play a particularly important role in controlling the availability of healthful foods, access to unhealthy foods, and the amount of physical activity and screen time. Teaching parenting skills is also required to enforce healthful changes (Young, Northern, Lister, Drummond, & O’Brien, 2007). Figure 22.1 Examples of Parent Involvement in Family-Based Behavioral Interventions Targeting healthful behavior changes and weight loss in parents is an important component of family-based behavioral interventions. Findings indicate that targeting both the parent and the child directly is associated with more robust child weight loss outcomes than targeting the child alone (Epstein, Wing, Koeske, Andrasik, & Ossip, 1981; Golan & Crow, 2004). Moreover, the degree of parental weight loss is positively correlated with child weight loss (Wrotniak, Epstein, Roemmich, Paluch, & Pak, 2005). During family-based behavioral interventions, parents participate in group sessions focused on teaching them how to use the Traffic Light Diet, increase their activity levels, and implement behavior change techniques for themselves. The same material is covered in separate parent and child groups each week, and the individual family meeting allows for the discussion of how parents and children will implement what they have learned into their daily routines. Family-based behavioral interventions have demonstrated their efficacy in achieving long-term improvements in weight outcomes. However, the intensive nature of involving the entire family may not be feasible in many real-world settings. Additionally, despite the success of family-based interventions, there is a sizable subset of youth who have difficulty making sustained behavior changes and do not achieve sufficient weight loss during treatment. To address these concerns, several adaptations of family-based behavioral interventions have been developed and tested. As discussed earlier, parents play a critical role as agents of lifestyle change to support child weight control (Wilfley, Vannucci, et al., 2010). Relative to family-based interventions targeting both parents and children in treatment, interventions that target parents only in childhood obesity treatment have the potential to provide more flexibility for families and be more cost effective for providers (Janicke et al., 2009). Parent-only interventions comprise the same components as family-based interventions, with the only difference being that all of the information is provided to the parent, who applies newly learned skills to the children and within the household (Golan, Kaufman, & Shahar, 2006). Some studies have shown that obese children assigned to parent-only interventions exhibited greater weight loss than family-based interventions (Golan et al., 2006), whereas other studies demonstrated no differences in child weight outcomes when comparing parent-only and family-based interventions (Boutelle, Cafri, & Crow, 2011; Janicke et al., 2008). Parent-only interventions may be most appropriate for use in very young children who developmentally assume only very limited responsibility for their behavior management. To overcome the challenge of weight loss and its maintenance presented by genetic vulnerability and the obesogenic environment, family-based interventions have expanded the focus of sustained behavior change beyond the individual and home (Wilfley, Van Buren, et al., 2010). This family-based behavioral social facilitation treatment builds on the lifestyle change skills learned in family-based behavioral interventions by extending treatment duration and practicing new skills across contexts (Wilfley, Van Buren, et al., 2010). Individual barriers to sustained self-regulation (e.g., impulsivity) are identified and addressed with tailored evidence-based strategies (for review, see Vannucci & Wilfley, 2012). Empowering families to build social support systems that promote healthy lifestyle choices is also a critical focus, as is increasing families’ awareness of environmental cues for making sustainable lifestyle changes (Wilfley, Van Buren, et al., 2010). These strategies have been shown to be effective in sustaining weight loss maintenance following participation in a traditional family-based behavioral intervention (Wilfley, Stein, et al., 2007; Wilfley, Van Buren, et al., 2010). Despite the success of family-based behavioral interventions, approximately 50% of youth either do not lose weight during treatment or regain weight soon after treatment cessation (Wilfley, Vannucci, et al., 2010). This is unsurprising, as the causes of obesity are heterogeneous in nature. Numerous risk factors that may predict excessive weight gain are not addressed in family-based interventions. Therefore, there has been a call for targeted interventions for youth who either exhibit a poor treatment response or report modifiable obesity risk factors (Ma & Frick, 2011). Targeting reductions in such aberrant eating patterns linked to obesity—including loss-of-control eating, eating in the absence of hunger, and emotional eating—may be important for achieving weight maintenance and obesity prevention (Shomaker, Tanofsky-Kraff, & Yanovski, 2010). Indeed, obese children and adolescents who are engaging in aberrant eating behaviors prior to the start of behavioral weight loss treatment may exhibit poorer weight outcomes in the short term (Wildes et al., 2010). Moreover, a sizable proportion (~30%–45%) of obese youths report these aberrant eating patterns (see Figure 22.2; Shomaker, Tanofsky-Kraff, & Yanovski, 2010). Although many novel targeted interventions are under development, three programs focused on reducing aberrant eating patterns during adolescence, middle childhood, and early childhood are reviewed briefly here. Figure 22.2 Proportion of Overweight and Obese Youth Reporting Aberrant Eating Patterns

Overweight and Obesity

OVERVIEW OF THE PROBLEM

Importance of Early Intervention

EVIDENCE-BASED APPROACHES

Expert Treatment Guidelines

Family-Based Behavioral Intervention

Dietary Modification

Energy Expenditure Modification

Behavior Change Techniques

PARENT INVOLVEMENT IN TREATMENT

ADAPTATIONS AND MODIFICATIONS

Adaptations of Family-Based Lifestyle Interventions

Parent-Only Interventions

Family-Based Behavioral Social Facilitation Treatment

Novel Targeted Interventions

Interpersonal Psychotherapy for the Prevention of Excess Weight Gain

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree