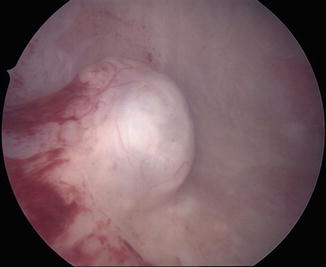

Fig. 9.1

Endometrial polyp occupying >50 of endometrial cavity

Fig. 9.2

Submucosal Type I leiomyoma seen in right cornual region of postmenopausal women

Physical Examination

Careful gynecologic examination should be included in the evaluation of all patients with the above complaints, and is useful for pre-procedure assessment and planning. Visualization of vagina and cervix are both necessary and must be easily obtainable if an office hysteroscopic procedure is to be considered. Cervix must be of normal shape and configuration without distorting features or severe stenosis. Vaginal discharge could be a symptom of pelvic inflammatory disease, which is an absolute contraindication for office hysteroscopy and must be evaluated and treated prior to procedure scheduling. The presence of cervical polyps can be an indication of endometrial polyps. Enlarged or irregular uterus may indicate the presence of uterine fibroids. Cervical pathologies such as cervical cancer must also be excluded. Bimanual pelvic examination allows assessment of the size and position of the uterus and any severe deviation or tethering which may have resulted secondary to prior cesarean sections, severe endometriosis or pelvic adhesive disease, adnexal pathology or fibroids. Severe enlargement of the uterus or deviation of the path of the cervical canal may indicate difficulty obtaining access and visualization of the endometrial cavity. Thus patients with these findings may be better suited to hysteroscopic procedures in the operating room. Patients should only be considered candidates for office hysteroscopic procedures if the cervix is easily visualized and accessible without severe distortion, deviation, enlargement, or stenosis. Endometrial cavity should also be felt to be of relatively normal positioning, shape and configuration such that the hysteroscope may be introduced into it with relative ease. If the examination indicates otherwise, then it is better to take the patient into the operating room under a deeper level of anesthesia which can allow a greater amount of manipulation of the cervix or uterus in order to accomplish the procedure.

Imaging

Assessment of endometrial and uterine pathology can benefit from well-established diagnostic tools, such as Transvaginal ultrasound (TVS) and Saline infusion sonography (SIS). Transvaginal ultrasound, in particular, is an inexpensive and noninvasive initial evaluation procedure for uterine diseases. It has sensitivity of 56 % and specificity of 72 % for the detection of any endometrial pathology. Saline infusion sonohysterography was introduced as an improved method for the diagnosis of endometrial diseases. In the evaluation of any endometrial pathology SIS has a sensitivty of 81% and a specificity of 100% [12]. For the evaluation of intracavitary masses, like submucous myomas and endometrial polyps Bonnamy et al. found sensitivities of 57 % and 95 % and specificities of 69 % and 77 % for TVS and SIS respectively [13]. The diagnosis of endometrial diseases such as hyperplasia or endometrial cancer cannot be distinguished by TVS or SIS, but can be suspected by increasing of endometrial thickness. Krampl et al. showed TVS and SIS had sensitivities of 33 % and 33 % with specificities of 88 % and 92 % respectively in the diagnosis of uterine structural abnormalities [14]. Soares et al. found TVS and SIS had sensitivities of 75 % and 50 %, specificities of 82 % and 96 % respectively [15]. Therefore, SIS is overall more benefitial for differentiating between focal lesions and diffuse endometrial thickening and is more accurate in the diagnosis of intracavitary masses (See Chap. 6 for more details on SIS).

Utilizing imaging for evaluating patients preoperatively to determine the extent of their pathology and determination of candidacy for an office procedure is extremely important. Pelvic ultrasound can show just a thickened endometrial stripe or may actually delineate a polyp or fibroid. If suspicious enough to warrant diagnostic hysteroscopy, decision to proceed with excision of polyp or fibroid can be made at the time of the hysteroscopy itself. If a small (<1 cm) submucosal fibroid or polyp is seen on ultrasound one can use SIS if readily available at the time of ultrasonography to further characterize the size and location of the polyp and the size of the pedicle of the submucosal fibroid for preoperative assessment. In general, polyps or fibroids on the anterior or posterior walls of the uterus are more accessible and thus more amenable to an office procedure versus pathology near the cornua or protruding off the fundus. Saline infusion ultrasonography is thus highly recommended for detailed assessment of endometrial pathology preoperatively in order to determine whether a case is simple enough to perform in the office, or is more complex, indicating that the operating room setting would be better suited to the case.

Patient Selection

Patients that have small polyps or single polyps or very small (<1 cm) submucosal fibroids with >80 % protrusion into the cavity are good candidates for attempt at an office procedure. Preoperative evaluation of the size and location of the pathology is very important. In addition patients must not have severely distorted cervical or uterine anatomy, a large fibroid uterus, stenotic cervix, or complex pathology in order to be candidates for office hysteroscopic operative procedures. Patients must also be motivated, have an understanding of the procedure, and able to be cooperative and patient during the procedure. Thus patients with a language barrier, high anxiety levels, or inability to understand or cooperate with the procedure should not be considered candidates for office-based surgery. Also, office hysteroscopy cannot be performed on patients with current uterine bleeding because of hindrance to adequate visualization of the cavity and pathology. In these cases, only high flow irrigation could provide satisfactory view of uterine cavity, which it is generally not possible in this setting because of small diameter of office hysteroscopes. Also, when dilatation and curettage is required, this may also be too painful to perform in the office setting. Thus, exclusion of cervical stenosis, severe cervical canal deviation, and recent uterine perforation must be undertaken prior to the procedure in order to decrease the risk of perforation. Uncooperative patients, cardiorespiratory disorders, cervical cancer, pelvic infections, and known intrauterine pregnancy are other contraindications for office hysteroscopy (Table 9.1).

Table 9.1

Contraindications to office operative hysteroscopic procedures

Contraindications for office hysteroscopy |

|---|

• Uncooperative patients |

• Cardiorespiratory disorders |

• Severely distorted cervical or uterine anatomy |

• Stenotic cervix |

• Cervical cancer |

• Large fibroid uterus |

• Current, active or heavy uterine bleeding |

• Recent uterine perforation |

• Pelvic infection |

• Intrauterine pregnancy |

Informed Consent

Once a patient is deemed a candidate for an office hysteroscopy procedure, a detailed discussion of the pathology and treatment options must be discussed with the patient. As in any surgical procedure, the reason for the procedure, risks, benefits, and alternatives to the procedure must be discussed and informed consent should be obtained; Chap. 3 provides a complete discussion of Informed Consent. Potential complications should be discussed. As the patient will be awake for the procedure, the expectations of the patient with regards to length of the procedure and any expected discomfort should be discussed. Motivation and cooperation of the patient and a desire to avoid anesthesia and the operating room setting must be present, as not all patients will wish to undergo an office procedure if given the option to go to the operating room. The patient must also know that the procedure may not be completed in the office setting and may be aborted at any point, and thus must understand that although the goal is to avoid going to the operating room, that this may still be a possibility if more extensive pathology is found.

The patient must also understand that mild cramping or bleeding after the procedure is not unusual after the office hysteroscopy, but that fever, severe abdominal pain, and heavy vaginal bleeding or discharge would be warning signs of complications or infection, and that the patient should immediately call the office or proceed to the emergency room if these develop. Although usually a safe procedure, complications including possible injury to the cervix or the uterus, infection, heavy bleeding, or side effects of medications used can occur and should be discussed with the patient.

Operative Procedure

Preop Preparation

History, physical examination, imaging, and discussion with the patient help determine what preoperative preparation, anesthesia requirements, and equipment may be required for the procedure. Adequate assessment and planning is truly what ensures the success of the procedure. Knowing what findings to expect and challenges that may be encountered allows the surgeon to anticipate and avoid difficulty or complications. For this reason, if an office procedure is desired, the extra step of performing a saline infusion sonogram in order to assess size and location of pathology can be worthwhile in most cases. Small polyps can generally be handled without energy or morcellation, whereas fibroids or larger polyps may need bipolar resection or morcellation and thus the equipment for these techniques must be readily available.

In order to reduce intraoperative pain and spasm of the uterus, preoperative treatment of the patient with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents such as ibuprofen or naproxen may be utilized to suppress prostaglandin production and thus prevent cramping and spasm of the uterus. Thus, having pre-procedural treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may improve the success of an office procedure as a common reason for aborting the procedure is Inadequate pain control. Dilation of cervix is also a painful component of the procedure and also has potential complications such as uterine perforation and cervical laceration. Difficulty with dilatation and stenotic cervix is more common in postmenopausal or nulliparous women and those receiving GnRH agonists. Numerous studies have been performed to examine the effect of preoperative administration of misoprostol to the pain and cervical dilation. They concluded that the use of misoprostol before hysteroscopy eases cervical dilation beyond 5 mm, decreases complication rates and is effective in pain reduction [16, 17]. Misoprostol also causes myometrial contractions which may reduce bleeding and facilitate resection of fibroids. Although there is no unified dosing recommendation, application regimen, or route of misoprostol use, generally administration of 400 mg misoprostol vaginally 6 h before hysteroscopy is recommended as a minimum application [18, 19]. Please see Chap. 1 for a more detailed discussion of preoperative misoprostol and other concerns for patient preparation before an office-based surgery.

Anesthesia

Anesthetic options are dependent on the patient and procedure and the agents that are available. Oral or intramuscular medications that are frequently utilized include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, narcotics, and benzodiazepine anxiolytic agents. For most patients undergoing a short procedure (<10 min) a combination of oral ibuprofen or naproxen or intramuscular ketorolac combined with a paracervical block utilizing local anesthetic agents is adequate. For longer procedures or more anxious patients the addition of an oral benzodiazepine such as alprazolam or lorazepam with or without oral narcotics such as oxycodone or hydrocodone may be useful. Some offices have the capability of intravenous sedative techniques which may include intravenous midazolam and/or fentanyl which may be used for more extensive procedures such as in patients with multiple polyps or who require resection of fibroids with energy, during which patients must be more relaxed. These sedative techniques however require special training and certification in monitored anesthesia care. In all patients the utility of a good paracervical block is essential as most of the pain control and pre-emptive prevention of postoperative pain results from blocking the nerve plexus innervating the uterus which enter at the level of the cardinal ligaments. Becoming proficient and comfortable with this technique is thus important. Please refer to Chap. 4 for procedural points on paracervical block and more details regarding anesthesia during office hysteroscopy.

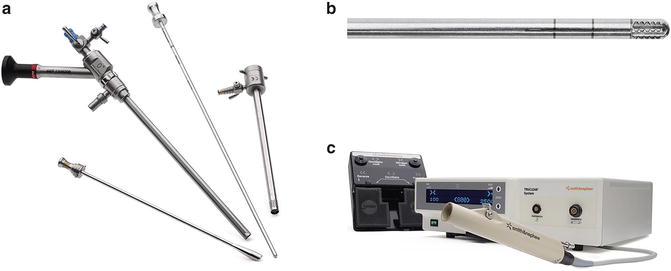

Instrumentation

Using rigid, semirigid, and flexible hysteroscopes with a small diameter gives physicians the opportunity to perform hysteroscopy without cervical dilatation. Since cervical dilatation is often the most painful part of hysteroscopy commonly causing procedure failure, this new instrumentation is allowing the increased use of office hysteroscopy for procedures beyond just diagnosis [20]. One of the first small diameter-rigid office hysteroscopes was the Office Continuous Flow Operative Hysteroscope, size 5 (Karl Storz, Tuttlingen, Germany). It consists of a 2.9 mm diameter rod-lens system with 30° vision angle and 5 mm sheath diameter. The newest version of this hysteroscope is Office Continuous Flow Operative Hysteroscope, size 4 (Karl Storz, Tuttlingen, Germany) which has thinner scope and outer diameter, 2 and 4 mm, respectively (Fig. 9.3). Both models include an oval shaped 5F operative channel through which small instruments such as graspers, biopsy forceps, or scissors can be placed (Fig. 9.4). The semirigid hysteroscope, Versascope (Gynecare, Ethicon Inc., Sommerville, NJ, USA) is characterized by 3.2 mm sheath diameter, 1.8 mm diameter, 28 cm length, 0° view scope and a single disposable outer sheath. An expandable working channel allows easy conversion from a diagnostic to a therapeutic procedure with 7F semirigid mechanical instruments or 5F bipolar electrodes. The flexible minihysteroscope is a more recent innovation. The new minihysteroscopes demonstrate similar benefits including less discomfort for patient [21]. The usefulness of flexible minihysteroscopes is restricted by higher costs for equipment; more difficult cleaning, disinfection, and sterilization; and reduced image size on the monitor screen compared with full-size standard hysteroscopy [21]. They do not yet accommodate operative instruments and thus are most useful as an initial step in evaluation of the cavity and extent of the pathology prior to proceeding with an operative procedure.

Fig. 9.3

Office continuous flow operative hysteroscope, size 4, with operating channel and hysteroscopic instrumentation (Copyright 2014 Photo Courtesy of KARL STORZ Endoscopy-America, Inc)

Fig. 9.4

Hysteroscopic scissors (top) and graspers (bottom) for use through operating channel of hysteroscope

Initial operative instruments included graspers, scissors, and biopsy forceps which can fit through a small operative channel in the office hysteroscope (Fig. 9.4). These were first used in office procedures for dealing with extremely small pathological changes such as small polyps, syncytia or directed biopsy of endometrial tissue. Development of bipolar systems of resection also benefitted office hysteroscopy. One of the newest bipolar electrosurgical systems is the Versapoint, characterized by a 1.6-mm-diameter (5-F), 36-cm-long, flexible electrode (Gynecare Inc., Somerville, NJ, USA) (Fig. 9.5). The configurations of the electrode are spring, twizzle, and ball electrodes, which are intended for vaporizing, cutting, and coagulating of the tissue, respectively. The most important advantage is its allowance of the utilization of physiological saline as a distention medium, thus reducing the risk of fluid overload and hyponatremia when compared with the use of monopolar systems with hypotonic solutions like glycine, sorbitol, or mannitol. Minimization of energy spread also makes procedures less painful and decreases the risk of skin burns at the bovine pad site [7].

Fig. 9.5

Versapoint (TM) hysteroscopic system with operating channel and 5Fr bipolar electrodes. Copyright 2014 Ethicon US LLC, Somerville, NJ, USA, Used with permission

The development of a bipolar resection system allowed for the utilization of safer bipolar energy with saline distention media for resection purposes. The use of the Gynecare Versapoint™ Bipolar Electrosurgery System has increased since its and it is the first bipolar system in the US market. It is used in combination with the Gynecare Versapoint™ Resectoscope which has a small 4 mm bore size and is available with either a 30° wide angle or a 12° lens (Fig. 9.6). By utilizing this system at the time of diagnostic hysteroscopy, it allows a single intervention to both diagnose and treat intrauterine pathology at the same time, thus reducing the cost. It can be utilized to remove submucosal myomas, polyps, intrauterine adhesions, or septa. Other bipolar resection systems are also now in development and becoming available on the market.

Fig. 9.6

Gynecare Versapoint™ resectoscope. Copyright 2014 Ethicon US LLC, Somerville, NJ, USA, Used with permission

Even more recently, the advent of mechanical hysteroscopic morcellators can eliminate the need for use of any type of energy, thus increasing the safety of the procedure. However, length of time of the procedure must be balanced with the benefit of the elimination of energy use. Despite a generally slower rate of resection, most morcellators however remove specimen fragments via suction thus eliminating the need for removal of fragments which may often be difficult in a patient who is awake. Two hysteroscopic morcellators are currently on the market in the United States. The Truclear™ hysteroscopic morcellator (Smith & Nephew, Andover, MA) (Fig. 9.7a) was approved by the US Food and drug administration in 2005 followed by approval of the MyoSure® Tissue Removal System (Hologic, Bedford, MA) in 2009. Both rely on a suction-based mechanical energy for tissue removal, rather than bipolar energy resection.

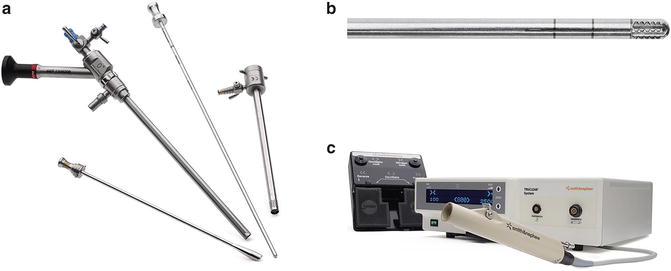

Fig. 9.7

(a–c) Truclear Hysteroscopic Morcellator: Smith & Nephew, Inc. Hysteroscopic morcellator showing basic equipment components (a), morcellator applicator with cutting window (b) and handpiece with (c) motor control unit (Copyright 2014 Smith&Nephew, Inc)

Truclear™ uses a single-use rigid metal inner tube with cutting edges that rotate and/or reciprocate within an outer tube with a side-facing cutting window at its distal end (Fig. 9.7b). The handpiece is reusable and is attached to a motor control unit (Fig. 9.7c). Suction is applied and tissue is pulled into the cutting window as the inner tube rotates at 1,100 rpm. The resected tissue is then aspirated through the device into a collecting pouch for later histopathologic analysis. For use in the office setting, rather than the original 9-mm outer diameter, rigid, continuous-flow, 0° hysteroscope, the newer 5.6 mm-diameter hysteroscope is used with the Truclear incisor plus blade 2.9. The MyoSure® system (Fig. 9.8) also relies on a suction-based, mechanical energy, rotating tubular cutter system to remove intrauterine tissue. It has a 2.5-mm inner blade that rotates and reciprocates within a 3-mm outer tube at speeds as high as 6,000 rpm and presents an outer bevel on the rotating blade edge. The blade and handpiece are combined into a single-use device that is then attached to suction and a motor control unit. An offset lens 6.25 mm, 0° continuous flow hysteroscope is used to introduce the unit into the endometrial cavity. With both devices, learning the correct resection technique, although not difficult, is of prime importance since the speed of morcellation is directly dependent on maintaining tissue contact between the cutting window and pathology, as well as the density of the pathology.

Fig. 9.8

MyoSure® tissue removal system (Hologic, Bedford, MA), courtesy of HOLOGIC, Inc. and affiliates

For polyps and Type I and Type II submucous myomas, hysteroscopic morcellation is a feasible alternative to traditional energy-based resection. Some studies have suggested that it can be both faster and easier to learn than traditional resectoscopy. Emanuel et al. showed a significant reduction in operating room time when removing polyps and Type I and Type II submucous myomas with a hysteroscopic morcellation device [22]. Ban Dongen and associates also randomized 60 patients with an endometrial polyp or a Type 0 or Type 1 myoma or Type I myoma to either hysteroscopic morcellation or loop-electrode resection by residents in training. The morcellation group demonstrated a 38 % reduction in operating room (OR) time (17 vs. 10.6 min; P = 0.008), a 32 % reduction in distention media used (5,050 vs. 3,413 mL; P = 0.041), and a marked reduction in the number of insertions and reinsertions of the hysteroscope to remove chips when the morcellator was used (number of insertions = 1 [range, 1–2]) compared with the resectoscope (number of insertions = 7 [range, 3–50]) [23]. As far as average time for procedure, Miller et al. reported average polyp morcellation times of 37 s and average myoma morcellation times of 6.4 min for Type 0, I, and II myomas with a mean diameter of 31.7 mm [24]. Given this relatively fast morcellation time, for smaller pathology and a limited number of lesions, it becomes conceivable to perform some of these procedures in the office with oral sedation and a paracervical block, thus reducing cost. The diameter of either the MyoSure hysteroscope (6.25 mm) or the smaller Truclear hysteroscope (5.0 mm) allows either system to be utilized for office-based treatments of polyps and Type 0 or I submucosal fibroids.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree