Evaluation of abnormal bleeding

• Premenopausal anovulatory women

• Premenopausal ovulatory women

• Postmenopausal bleeding

Evaluation of infertility

• Routine infertility work-up

• Abnormal HSG

• Pre-IVF evaluation

• Recurrent spontaneous abortion

Evaluation of abnormal TVUS or SIS when endometrium is:

• Not visualized

• Indeterminate

• Indistinct

• Not visualized in its entirety

Localization of foreign body

• Lost IUD

• Migration of cerclage

Postoperative evaluation

• Inspection of cavity following hysteroscopic myomectomy or polypectomy

• Inspection of cavity following abdominal myomectomy entrance into endometrial cavity

• Difficult postpartum D&C to evaluate for Asherman syndrome

• After removal of indwelling Foley catheter following adhesiolysis

• Inspection of cesarean scar

• Inspection following septum repair

• Recurrent bleeding after endometrial ablation

• Inspection of Essure device if migration of the device suspected or for irregular bleeding

Classification of submucosal fibroids

• Class I

• Class II

• Class III

Evaluation of the endometrium following UFE

• Evaluate complaints of amenorrhea

• Evaluate complaints of post-UFE cramping

• Evaluate complaints of chronic or episodic leukorrhea

• Evaluate the endometrium for submucosal fibroids when MRI is equivocal

Evaluation of the pregnant patient

• IUD localization in early pregnancy

• Retained products of conception

• Postpartum hemorrhage

• Ectopic pregnancy (tubal or interstitial)

• Failed termination of pregnancy

• Persistent bleeding after termination of pregnancy

Endometrial cancer

• Staging

• Evaluation of cervical involvement

• Second look after nonsurgical treatment

Hysteroscopic tubal occlusion

• Determine if there is any obstruction to tubal ostia

• Determine if there are other intracavitary lesions that need removal

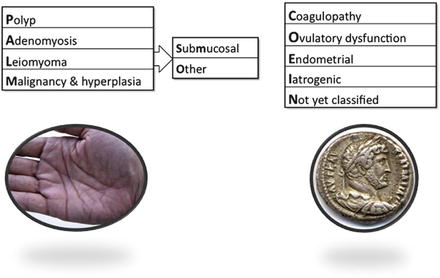

Table 7.2

PALM-COEIN basic classification system

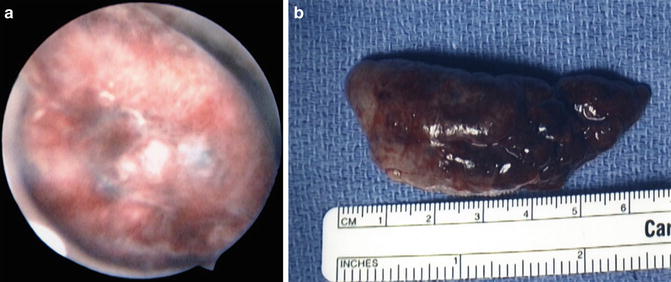

Fig. 7.1

(a) Endometrial polyp filling the endometrial cavity. (b) Gross specimen of endometrial polyp from (a)

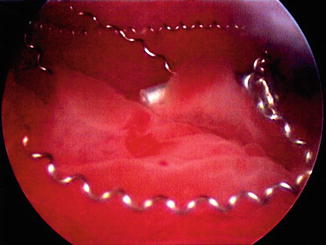

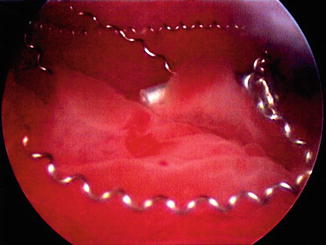

Fig. 7.2

Submucosal leiomyoma

Abnormalities of reproduction also serve as an indication of office hysteroscopic surgery. Both the evaluation of infertility or subfertility can be assisted by endometrial evaluation with hysteroscopy which may show intrauterine synechae or adhesions or a uterine septum. Evaluation of abnormal hysterosalpingography (HSG) is another indication as well as final appraisal of the intrauterine environment prior to beginning of in vitro fertilization (IVF). Also, tubal blockage may be identified and treated with office techniques. Post reproductive complications such as retained placenta postpartum or incomplete pregnancy termination can be diagnosed using office hysteroscopy. This is especially important in patients who may have a negative urine or serum hcg (human chorionic gonadotropin) level on laboratory testing but where office hysteroscopy reveals retained gestational tissue which is causing abnormal bleeding or impaired subsequent fertility.

Other indications for office hysteroscopy include inspection of the uterine cavity after operative hysteroscopy for large polyps or submucosal leiomyoma or evaluation of abnormal bleeding after global endometrial ablation. Difficult or complicated surgery for pregnancy loss with dilatation and curettage (D&C) can lead to adhesions or after D&C for postpartum bleeding in order to assess removal of all gestational tissue. Lastly, after tubal sterilization, endometrial appraisal may be helpful to assess placement or disturbance from the microcoil inserts (Fig. 7.3).

Fig. 7.3

Example of unwound Essure™ microcoils displaced throughout the endometrium in a patient with heavy menses after hysteroscopic sterilization

Uterine fibroid embolization (UFE) is increasingly becoming a procedure to decrease menstrual bleeding from symptomatic uterine leiomyomata. After the procedure, the leiomyomata and surrounding uterine muscular and secretory tissue can become hypoperfused, leading to atrophy and pale, nonviable endometrium: adhesions, fibrosis, and calcifications may also develop. All of these factors can lead to development of an onerous vaginal discharge, at times described as clear, yellow, brown, or rusty. Office hysteroscopy is the ideal tool to evaluate these complaints. The performance of this can help in diagnosis and to decide what, if any, therapy is needed. Commonly, expectant management is all that is needed but patients can respond well to operative hysteroscopic resection of the necrotic tissue [5]. Also, after UFE, one study showed that up to 22 % of patients will require subsequent surgery months or years after UFE, with many of the surgeries hysteroscopic in nature [6].

Planning for hysteroscopic resection of submucosal leiomyomata based on transvaginal ultrasound or saline infusion sonography (SIS) would benefit from office hysteroscopy prior to the operative resection: hidden pathology in the form of multiple fibroids, polyps, or adhesions can be identified and the surgical approach may be modified if needed. For instance, a multiple stage resection may be needed for large or multiple submucosal myomas if the risk of hyperosmotic fluid absorption puts the patient at risk. As noted hysteroscopist Dr. Linda Bradley recommends, “Avoid surprises in the operating room” [7].

Evaluation of postmenopausal bleeding can be easily accomplished in the office, especially when the patient may have comorbid medical conditions making operative evaluation in the OR or ASC more problematic. Bleeding can occur within the first few years after the menopause transition or may not occur until 20–25 or more years past menopause. While not all postmenopausal bleeding indicates malignancy or even endometrial hyperplasia, suspicion of this type of pathology should be increased in the face of risk factors including obesity, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and unopposed estrogen replacement therapy. Patients with these factors or those with transvaginal ultrasound showing double layer endometrial thickness of greater than 5 mm should undergo office endometrial biopsy. However, office pipelle biopsy has shown to miss focal lesions in the endometrium, with a sensitivity ranging from 83 to 98 % [8, 9]. Thus, office hysteroscopy is strongly recommended in patients who have continued postmenopausal bleeding after a negative endometrial biopsy. Focal and specific hysteroscopic directed biopsies can be performed at the time of office hysteroscopy, providing an accurate diagnosis.

Women taking tamoxifen for adjunct therapy for breast cancer also can benefit from office hysteroscopy. Tamoxifen, a nonsteroidal triphenylethylene derivative, has been shown to increase survival in patients with estrogen receptor-positive tumors. In the breast, tamoxifen works as an estrogen antagonist but in the endometrium, it has a weak estrogen agonistic effect and is thus a mixed agonist/antagonist. Women taking tamoxifen need monitoring during and after therapy for the development of atypical endometrial hyperplasia and malignancy. Routine screening with ultrasound and/or endometrial biopsy is not recommended as false positive rates are increased [10]. In patients who are currently or have ever received tamoxifen develop frank vaginal bleeding, spotting/staining or even brown or unusual vaginal discharge should undergo direct visualization of the endometrium with hysteroscopy as visualization is more accurate in diagnosing frank pathology. In these women, a variety of endometrial patterns can be seen on hysteroscopy, including pale atrophy or alternatively, a hypervascularized pattern in addition to a cystic appearance reported to be from activation of subendothelial adenomyotic glands and cysts [11, 12]. Also, the incidence of endometrial polyps is significantly increased in women receiving tamoxifen: reported incidences of 32–57 % have been reported [13] (Table 7.3).

Table 7.3

Incidence of hysteroscopically confirmed endometrial polyps in women receiving tamoxifen

Author | Year | No. patients on tamoxifen | No. patients with polyp (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

DeMuylder et al. | 1991 | 23 | 13 (57) |

Lahti et al. | 1994 | 49 | 17 (35) |

Mouritas et al. | 1999 | 22 | 7 (32) |

Leidman | 2000 | 35 | 18 (51) |

Also, evaluation of an abnormal transvaginal ultrasound result may benefit from office hysteroscopic assessment in addition to or in place of endometrial sampling. Given increasingly specific ultrasound reports, not only may double layer endometrial thickness be reported, but other endometrial findings such as endometrial or subendometrial cysts, calcifications, or endometrial fluid may be described as well as less well-defined terms such as “space-occupying lesion.” These descriptions may indicate polyps, submucosal leimyomata, malignancy or atypical hyperplasia or adenomyosis. Fluid in the endometrium has been described by many and can be associated with cervical stenosis as well as endometrial pathology. Vuento and colleagues reported that in a group of over 1,000 asymptomatic postmenopausal women, 12 % had fluid in the endometrium with 5 % of these patients having endometrial pathology, including cancer [14]. Techniques are available to assist in the office with overcoming cervical stenosis if present and then office hysteroscopy can be done along with directed biopsies and/or endometrial biopsy as indicated.

Lastly, patients will present with an intrauterine device (IUD) where the stings have been withdrawn into the endometrial cavity or are missing. Also, older models such as the Lippes loop or those from manufacturers outside the United States may not have strings attached, thus requiring either blind uterine manipulation or hysteroscopy to remove them. Alternatively, an IUD with visible strings that is difficult to remove due to cervical stenosis or possible uterine embedment will be easily assessed with office hysteroscopy. In the United States, IUD use is increasing for both contraception as well as for gynecologic treatment with the levonorgestrel releasing IUD (LNG-IUD). As such, complications with IUD can be more easily diagnosed in office with hysteroscopy. Also, if one has a sheath with an operating channel in office, utilizing the operating channel with hysteroscopic grasping forceps can be utilized to remove the IUD in one setting in the office, providing another example of a “see and treat” philosophy of office hysteroscopic surgery. The strings can be moved to the ectocervix while leaving the IUD in utero or the IUD can be removed if it has expired, is causing complications or if the patient desires pregnancy. Office hysteroscopy can also determine if the IUD is embedded into the myometrium (Fig. 7.4). At times, the initial evaluation in office can determine if removal of the embedded IUD can be accomplished in office with an operative approach or if a more involved surgery with hysteroscopy (and or laparoscopy if needed) is required to remove the impacted IUD. Other types of foreign bodies that may be retrieved with the in-office technique of hysteroscopy include lost laminarium or portions of laminaria, surgical gauze, Essure™ microcoil and fetal bone after incomplete pregnancy termination.

Fig. 7.4

Embedded levonorgestrel IUD

Contraindications to Office Hysteroscopy

There are several major contraindications to office diagnostic hysteroscopic surgery. Current pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) is the leading absolute contraindication. If PID is suspected (fever, uterine tenderness, and/or adnexal masses), the procedure should be postponed and evaluation to confirm the diagnosis and establish treatment should be initiated. Past episodes of PID may predispose to hydrosalpinx or other obstructions of the endometrium or salpinges, thus consideration of pre and postoperative antibiotics should be considered.

Recent cervical infection, if treated, is not a contraindication though if compliance with treatment is suspected, the office procedure should be delayed until negative cervical cultures are verified. Current or active herpesvirus infection is another absolute contraindication to the performance of hysteroscopy. Vigilance when obtaining a patient history is required to be certain an asymptomatic herpes infection is not present and if lesions are seen when prepping the patient, delaying the hysteroscopy is important. The presence of cervical cancer has been proposed as an absolute contraindication as concern about dissemination of malignant cells. Pregnancy is a relative contraindication to performance of hysteroscopy in the office. While a hysteroscopic procedure may be needed in early pregnancy to remove an IUD, it is suggested to perform this in the operating room under low pressure using only saline for distention (carbon dioxide poses risk of gas embolism). In the presence of heavy and profuse vaginal bleeding, office hysteroscopy may be difficult with smaller caliber hysteroscope (so-called “mini-hysteroscopes”) due to problems maintaining adequate irrigation and uterine insufflation. An uncooperative patient is another relative contraindication as patient compliance with ability to remain relatively still during the procedure and tolerate the possibility of mild discomfort is needed: discussion of the benefits of office hysteroscopy must be weighed with a patient’s ability to cooperate.

Instrumentation for Office Hysteroscopy

As mentioned, office hysteroscopy has evolved with improvements in technology and the development of small diameter hysteroscopes and improved fiberoptics and video monitoring. Instrumentation for office hysteroscopy has two options: rigid and flexible. There are documented benefits of each type of equipment in addition to the experience and training of the physician performing the office procedure.

Rigid hysteroscopy has been used the longest with reports generated from the late 1970s and early 1980s reporting on office hysteroscopy in-office. Advances since then have yielded current rigid hysteroscopes for use in office have a diameter ranging from 1.2 to 4 mm with continuous flow features as well as improved visualization and coupled with the diagnostic sheath, these scopes have a final diameter that does not exceed 5 mm (Fig. 7.5). Nagele et al. demonstrated success in outpatient diagnostic hysteroscopy in 2,500 patients of over 96 % using a 4-mm telescope with a 5-mm diagnostic sheath [2]. With these smaller diameter telescopes, there are different angled lenses that can help facilitate visualization of the endometrial cavity: 30, 12, and 0-degree objective lens angulations are available, with 12 and 30-degree being used more commonly in the office setting (Fig. 7.6a, b).

Fig. 7.5

Karl Storz rigid hysteroscope (copyright 2014 photo courtesy of KARL STORZ Endoscopy-America, Inc.)

Fig. 7.6

Example of hysteroscope with a 12° deflected view (a) and a 30° deflected view (b) (copyright 2014 photo courtesy of KARL STORZ Endoscopy-America, Inc.)

Flexible hysteroscopy utilizes zero degree lens with a bendable tip that allows a bidirectional mode allowing for up to a 120-degree field of vision along a long working sheath that includes a channel for distending media (Fig. 7.7). There are adaptors available which will create an ancillary port, which when used as an operative channel, can be used to obtain directed biopsies or to retrieve IUD strings or remove small polyps. Bradley demonstrated in over 400 women that office flexible hysteroscopy is well tolerated and cost effective for evaluation of menstrual disorders [15].