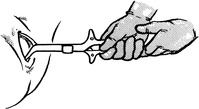

Making an incision in the perineal body at the time of delivery.

Indications

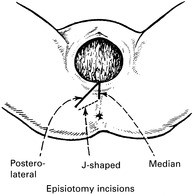

Types of Incision

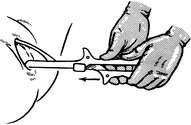

Technique

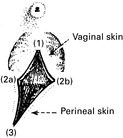

Repair

FORCEPS DELIVERY

Indications for the use of forceps

Conditions for forceps delivery

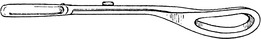

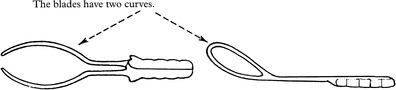

OBSTETRIC FORCEPS

Low Forceps

Mid Forceps

Wrigley’s Forceps

Anderson’s (Simpson’s) Forceps

Kielland’s Forceps

FORCEPS DELIVERY

Preparations

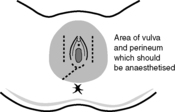

Anaesthesia

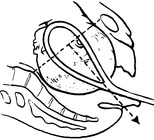

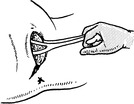

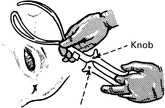

Pudendal Nerve Block

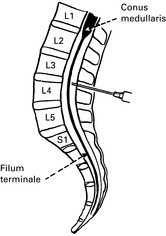

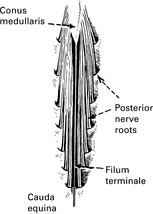

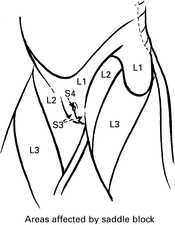

Physiology of Spinal Anaesthesia

Circulatory Effects

LOW FORCEPS DELIVERY

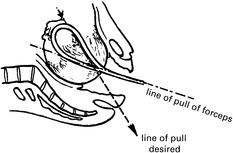

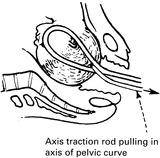

MID FORCEPS DELIVERY

DELIVERY WITH KIELLAND’S FORCEPS

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree