Chapter 10 Obstetric Hemorrhage and Puerperal Sepsis

Antepartum Hemorrhage

Antepartum Hemorrhage

It is critical for the well-being of both the mother and the fetus that the patient who presents with third-trimester bleeding be evaluated and managed emergently. The differential diagnosis of third-trimester bleeding is listed in Box 10-1.

Abnormal Placentation

Abnormal Placentation

CLASSIFICATION

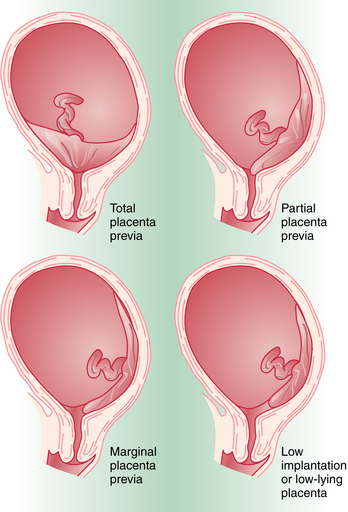

Placenta previa is classified according to the relationship of the placenta to the internal cervical os (Figure 10-1). Complete placenta previa implies that the placenta totally covers the cervical os. A complete placenta previa may be central, anterior, or posterior, depending on where the center of the placenta is located relative to the os. Partial placenta previa implies that the placenta partially covers the internal cervical os. A marginal placenta previa is one in which the edge of the placenta extends to the margin of the internal cervical os.

Abruptio Placentae

Abruptio Placentae

PREDISPOSING FACTORS

Factors associated with an increased incidence of abruption are noted in Box 10-2. The most common of these risk factors is maternal hypertension, either chronic or as a result of preeclampsia. The risk for recurrent abruption is high: 10% after one abruption and 25% after two.

Uterine Rupture

Uterine Rupture