3.4 Obesity

Introduction

• Obesity is a chronic disorder of energy imbalance – focus upon both sides of the energy balance equation: energy in and energy out.

• Measure body mass index (BMI) and plot on a BMI-for-age chart. Measure and record waist circumference, and calculate waist : height ratio.

• In pre-pubertal children, weight maintenance or reduction in the rate of weight gain, may be appropriate goals of therapy. Weight loss is often necessary for moderately obese younger children, and for adolescents.

• For younger children, focus upon the parents as agents of change. Adolescents will require a different, developmentally sensitive, approach.

• Long-term behavioural change is required, involving an increase in incidental physical activity, a reduction in sedentary behaviour and a sustainable change to a lower energy intake.

• There is a role for drug therapy in adolescents who have moderately severe obesity, or those with clinical insulin resistance.

• Prevention of obesity requires a whole-of-system approach in which many aspects of the broader food and physical activity environment are targeted.

How is paediatric overweight and obesity defined?

Body mass index – a measure of total body fatness

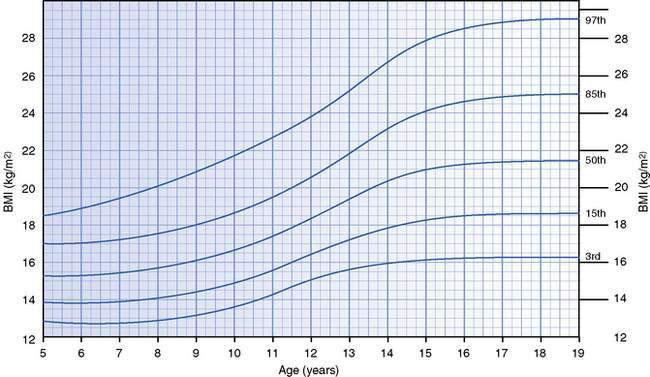

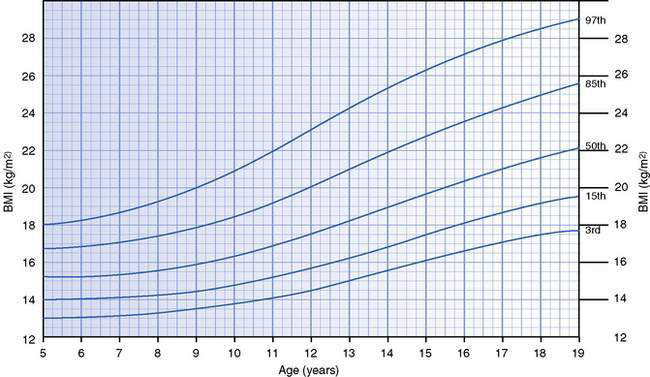

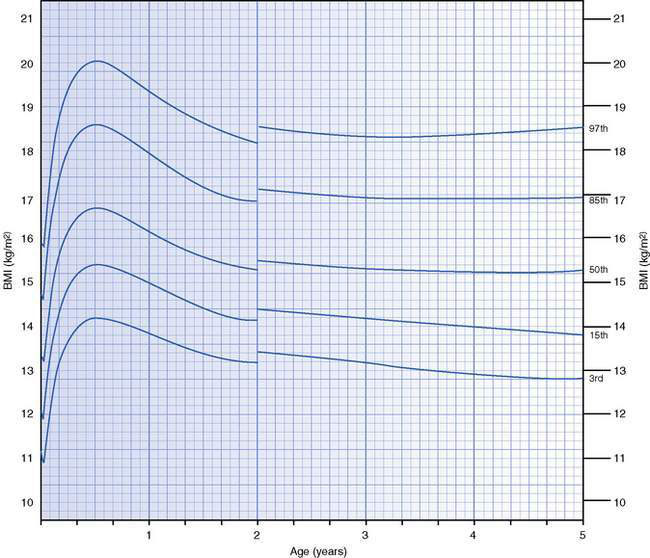

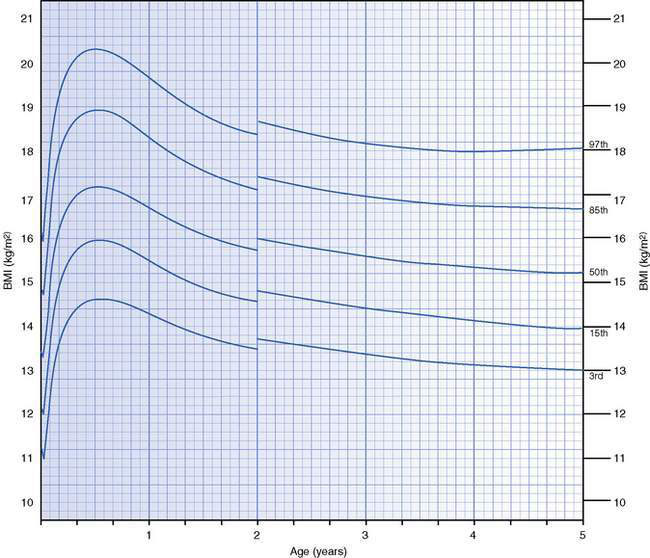

Body mass index (BMI; weight/height2; kg/m2) is a simple measure of body fatness. BMI varies dramatically with age and sex during childhood and adolescence: it increases in the first year, falls during preschool years, and then rises once more into adolescence. The point at which BMI starts to increase again, between 4 and 7 years of age, is termed the point of ‘adiposity rebound’ (Figs 3.4.1–3.4.4).

Fig. 3.4.1 Body mass index-for-age chart for girls aged 5–19 years.

Source: 2007 World Health Organization Reference. Available at: http://www.who.int/growthref/cht_bmifa_girls_perc_5_19years.pdf

Fig. 3.4.2 Body mass index-for-age chart for boys aged 5–19 years.

Source: 2007 World Health Organization Reference. Available at: http://www.who.int/growthref/cht_bmifa_boys_perc_5_19years.pdf

Fig. 3.4.3 Body mass index-for-age chart for girls aged 0–5 years.

Source: World Health Organization Child Growth Standards. Available at: http://www.who.int/childgrowth/standards/cht_bfa_girls_p_0_5.pdf

Fig. 3.4.4 Body mass index-for-age chart for boys aged 0–5 years.

Source: World Health Organization Child Growth Standards. Available at: http://www.who.int/childgrowth/standards/cht_bfa_boys_p_0_5.pdf

Several countries have their own BMI-for-age growth charts that can be used clinically to chart an individual’s BMI and monitor changes over time. The World Health Organization has also developed BMI-for-age charts for international use for children aged 0–5 and 5–19 years (see Figs 3.4.1–3.4.4). Until further research helps establish the relation between BMI-for-age cut-points and health outcomes in childhood and adolescence, the decision as to which specific centile lines denote overweight and obesity in clinical settings ultimately remains arbitrary.

What is the prevalence of paediatric overweight and obesity?

What are the complications of paediatric obesity?

The complications of obesity among children and adolescents may be immediate or may not manifest until the medium- to long-term. They affect many body systems, as outlined in Table 3.4.1.

Table 3.4.1 Potential obesity-associated complications in children and adolescents

| System | Health problems |

|---|---|

| Psychosocial | Social isolation and discrimination, decreased self-esteem, learning difficulties, body image disorder, bulimia Medium and long term: poorer social and economic ‘success’, bulimia |

| Respiratory | Obstructive sleep apnoea, asthma, poor exercise tolerance |

| Orthopaedic | Back pain, slipped femoral capital epiphyses, tibia vara, ankle sprains, flat feet |

| Hepatobiliary | Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, gallstones |

| Reproductive | Polycystic ovary syndrome, menstrual abnormalities |

| Cardiovascular | Hypertension, adverse lipid profile (low HDL cholesterol, high triglycerides, high LDL cholesterol) Medium and long term: increased risk of hypertension and adverse lipid profile in adulthood, increased risk of coronary artery disease in adulthood, left ventricular hypertrophy |

| Endocrine | Hyperinsulinaemia, insulin resistance, impaired glucose tolerance, impaired fasting glucose, type 2 diabetes mellitus Medium and long term: increased risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus and metabolic syndrome in adulthood |

| Neurological | Benign intracranial hypertension |

| Skin | Acanthosis nigricans, striae, intertrigo |

HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein.

Complications during childhood and adolescence

Endocrine complications

Overweight children are much more likely to have raised fasting insulin concentrations (indicative of insulin resistance), impaired fasting glucose or glucose intolerance than their lean peers. Although still rare among children and adolescents, the incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus is increasing and is inextricably linked to the prevalence of obesity among young people. Type 2 diabetes is more common in adolescents and those who are obese, have acanthosis nigricans (thickened pigmented skin at the base of the neck and in flexures, characteristic of insulin resistance; Fig. 3.4.5), have a family history of type 2 diabetes or are female.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree