15 Obesity

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Clinical Presentation

BMI is calculated using a formula (weight (kg) ÷ [height (m)]2) or by using a BMI calculator, such as that provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (http://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/index.html.) BMI should be calculated and plotted on the appropriate standardized graph to ascertain the BMI percentile at every well-child visit.

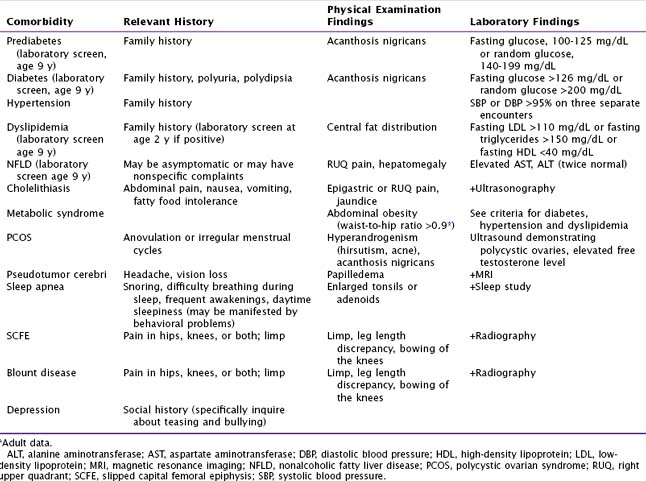

Laboratory evaluation such as fasting glucose, liver enzymes (alanine aminotransferase [ALT], aspartate aminotransferase [AST]), and fasting lipids are used to screen patients for the common comorbidities associated with obesity. Additional tests should be ordered based on the history and physical examination (Table 15-1).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree