13 Nutritional Requirements and Growth

Nutritional Requirements

Calories

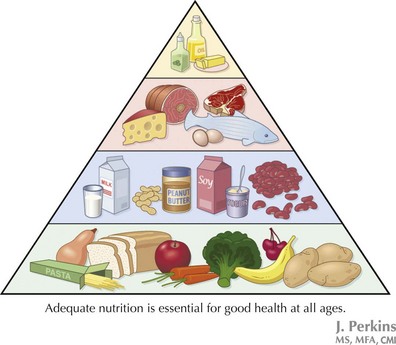

Neonates need approximately 110 to 120 kcal/kg/d for appropriate growth. Calorie requirements steadily decrease to approximately 90 kcal/kg/d in toddlers. After 3 years of age, calorie requirements vary by gender, age, weight, and activity. Children with very low levels of activity, such as children with profound mental or motor disability who receive tube feedings, usually have significantly lower energy requirements than healthy children. When offered but not forced to take food, most infants and children are able to self-regulate their calorie, or energy, intake to optimal levels over time. Children are generally able to increase their calorie intake when needed, such as during brief periods of rapid weight gain in infancy and pubertal growth spurt and then decrease their intake back to appropriate levels for typical growth. If a toddler is gaining weight well, parents of picky eaters should provide healthy food options and can be reassured that the child is appropriately regulating his or her calorie intake (Figure 13-1).

Micronutrients

This section briefly discusses three of the most important micronutrients and the problems that can arise when they are deficient. Chapter 16 addresses these and other deficiencies in more detail.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree