Chapter 43 Nutrition, Food Security, and Health

Malnutrition as the Intersection of Food Security and Health Security

Undernutrition is usually an outcome of 3 factors: household level food security, access to health and sanitation services, and child caring practices. A mother with few economic resources who knows how to care for her children and is enabled to do so can often use available food and health services to produce well-nourished children. If food resources and health services are available in a community, but the mother does not access immunizations or does not know how or when to properly add complementary foods to her child’s diet, that child might become malnourished (Table 43-1).

Table 43-1 THREE MYTHS ABOUT NUTRITION

From World Bank: Repositioning nutrition as central to development, 2006 (PDF). http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/TOPICS/EXTHEALTHNUTRITIONANDPOPULATION/EXTNUTRITION/0,contentMDK:20787550~menuPK:282580~pagePK:64020865~piPK:149114~theSitePK:282575,00.html. Accessed May 23, 2010.

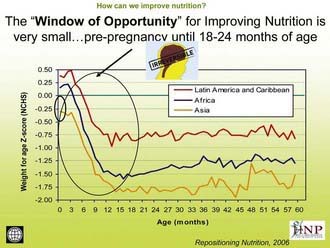

Undernutrition

The greatest risk of undernutrition occurs during pregnancy and in the first 2 years of life (Fig. 43-1); the effects of this early damage on health, brain development, intelligence, educability, and productivity are potentially irreversible (Table 43-2). Governments with limited resources are therefore best advised to focus publicly funded actions on this critical window of opportunity, between preconception and 24 mo of age. Folate deficiency also increases the risk of birth defects; this particular window of opportunity is before conception, as it is with iodine. Iron deficiency anemia is another dimension of undernutrition that has measurable risks that extend outside of the early years of life, with particular risks to the health of a mother as well as for the birth weight of her child. Anemia can also reduce physical and cognitive function and economic productivity of adults of both sexes.

Figure 43-1 The window of opportunity for improving nutrition is very small: prepregnancy until 18-24 mo of age.

(From The World Bank’s Human Development Network: Better nutrition = less poverty: repositioning nutrition as central to development: a strategy for large scale action, 2006 [PDF]. http://siteresources.worldbank.org/NUTRITION/Resources/281846-1114108837888/RepositioningNutritionLaunchJan30Final.pdf. Accessed May 23, 2010.)

Table 43-2 WHY MALNUTRITION PERSISTS IN MANY FOOD-SECURE HOUSEHOLDS

From World Bank: Repositioning nutrition as central to development, 2006 (PDF). http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/TOPICS/EXTHEALTHNUTRITIONANDPOPULATION/EXTNUTRITION/0,contentMDK:20787550~menuPK:282580~pagePK:64020865~piPK:149114~theSitePK:282575,00.html. Accessed May 23, 2010.

Measurement of Undernutrition

The term malnutrition encompasses both ends of the nutrition spectrum, from undernutrition (underweight, stunting, wasting, and micronutrient deficiencies) to overweight. Many poor nutritional outcomes begin in utero and are manifest as low birthweight (LBW). Prematurity and intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) are the two main causes of LBW, with prematurity relatively more important in developed countries and IUGR relatively more important in developing countries (Chapter 90).

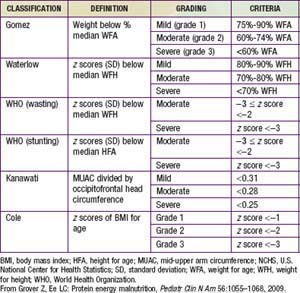

In preschool- and school-aged children, nutritional status is often assessed in terms of anthropometry. International references have been established that allow normalization of anthropometric measures in terms of z scores defined as the child’s height (weight) minus the median height (weight) for the age and sex of the child divided by the relevant standard deviation (Table 43-3). The World Health Organization (WHO) recently revised the child growth references based on data from healthy children in 5 countries. Comparisons of malnutrition rates across countries are meaningful, and these growth references are applicable to all children across the globe.

Height for age is useful for assessing the nutritional status of populations, because this measure of skeletal growth reflects the cumulative impact of events affecting nutritional status that result in stunting and is also referred to as chronic malnutrition. This measure contrasts with weight for height, or wasting, which is a measure of acute malnutrition. Weight for age is an additional commonly used measurement of nutritional status. Although it has less clinical significance because it combines stature with current health conditions, it has the advantage of being somewhat easier to measure: Current weighing scales allow a child to be weighed in a caregiver’s arms, but weight for height requires 2 different instruments for measurement. Height for age is particularly difficult to measure for the most vulnerable children <2 yr of age for whom recumbent length is the preferred indicator for height. In emergencies and in some field settings, mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) is often used for screening in lieu of weight for height (see Table 43-3).

Another dimension of malnutrition is micronutrient deficiencies. The micronutrients of particular public-health significance are iodine, vitamin A, iron, folic acid, and zinc. Iodine deficiency and its sequelae (goiter, hypothyroidism, and developmental disabilities including severe mental retardation) are assessed by clinical inspection of enlarged thyroids (goiter) or by iodine concentrations in urine (µg/L). Even mild forms of iodine deficiency during pregnancy have been implicated in poor mental and physical development among children as well as fetal losses. The public-health benchmark for eliminating iodine deficiency in a population is <20% of the population with urinary iodine levels <50 µg/L (Chapter 51).

Vitamin A deficiency is caused by low intake of retinol or its precursor, beta-carotene. Absorption can be inhibited by a lack of fats in the diet or by parasite infestations. Clinical deficiency is estimated by combining night blindness and eye changes—principally Bitot spots and total xerophthalmia prevalence. Subclinical deficiency is assessed as prevalence of serum retinal concentrations <0.70 µmol/L (Chapter 45). The greatest public-health significance of vitamin A deficiency is its association with a higher mortality among young children. Prophylactic supplementation of vitamin A among deficient populations for children <5 yr of age can reduce child mortality by as much as 23%.