10 Nutrition

• Children’s nutritional needs vary as they grow.

• Children’s nutritional needs are influenced by their state of health.

• A wide range of food choices and feeding behaviors are used to meet nutritional needs.

• Recommended dietary allowances are guidelines only.

• Parents and other caregivers are responsible for providing food choices that are nutritionally adequate and for establishing healthy eating patterns; to do so, they must be well informed.

• Family patterns of nutrition and eating are based on social, economic, cultural, and psychological dynamics. Patterns are not related to nutrients alone.

• The primary care provider is a source of information regarding nutrition, feeding patterns, and health.

• The primary care provider works with a network of specialists (e.g., registered dietitians) to manage children’s nutrition status.

Standards for Preventive Care

Standards for Preventive Care

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends exclusive breastfeeding until 4 to 6 months old, and continued breastfeeding, supplemented with appropriate foods for infants, until at least 12 months old (AAP, 2005). The AAP also recommends giving 400 International Units of vitamin D to all breastfed infants until 1 year of age and to all children and adolescents with diets deficient in vitamin D (Wagner et al, 2008). The American Medical Association (AMA) supports breastfeeding as the best infant nutrition. It recommends that providers calculate body mass index (BMI) measures in children’s routine physical examinations, “recognizing ethnic sensitivities and its relation to stature.” The AMA school health advocacy agenda includes attention to healthy eating and exercise in schools and for school-age children (AMA, 2005). The Institute of Medicine (IOM) has published ways to ensure that school food programs meet current dietary recommendations (Committee on Nutrition Standards for National School Lunch and Breakfast Programs et al, 2010). Bright Futures in Practice: Nutrition (Holt and Wooldridge, 2011) presents nutritional guidelines, discusses issues and concerns related to pediatric nutrition, and outlines tools for providers to assess and manage nutrition in children. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends that children ages 6 years and older be screened for obesity and that they be given, or referred for, comprehensive intensive behavioral interventions to improve weight (USPSTF, 2010). Nutrition standards for children emphasize that:

• Breast milk is the best food for infants.

• Children’s diets should include a wide variety of foods.

• Foods should come predominantly from plants, especially:

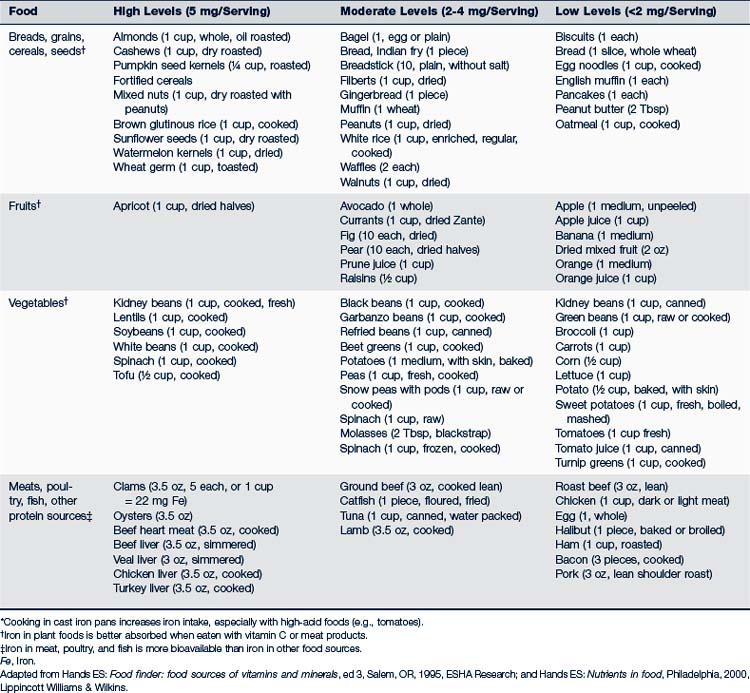

• Iron-rich foods are essential, especially for infants and adolescents.

• Fat intake, particularly saturated fats and cholesterol, should be limited. Trans fats should be eliminated from the diet.

• Simple carbohydrates (e.g., refined grains, white bread, sugar, high-fructose corn syrup, sodas) should be limited.

• Extra calcium, iron, and folic acid are important nutrients in adolescent girls’ diets.

• Children’s diets should include adequate fiber and sodium.

Nutritional Requirements and Recommended Daily Intake

Nutritional Requirements and Recommended Daily Intake

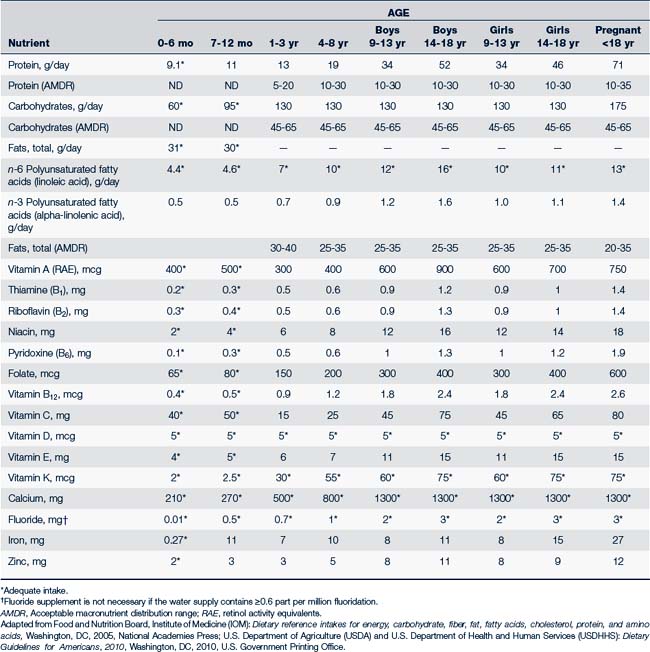

Energy

Macronutrients (protein, carbohydrates, and fats) and alcohol are all sources of calories the body uses to meet its energy needs. The body makes no distinction as to the source of calories; it will use whichever calories are consumed. It is recommended, however, that caloric intake be distributed among the three macronutrients, with each providing a certain percentage of total daily caloric intake. These recommendations are given as an acceptable macronutrient distribution range (AMDR) and are presented in Table 10-1. They are based on age for children who are of average height, weight, and physical activity level (FNB, 2005; USDA and USDHHS, 2010). If more calories than are required for energy needs are consumed, they will be converted to fat and stored. In addition to energy needs, the body requires essential nutrients for growth and health. If the food a child eats is high in calories (calorie dense) but low in nutrients (nutrient poor, often referred to as “empty calories”), the child will gain excess weight and still be undernourished. Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) from 2001 to 2004 show that more than 90% of all children ages 2 years and older had intakes of empty calories that exceeded discretionary limits (Krebs-Smith et al, 2010), contributing to overweight and obesity.

Water and Electrolytes

Water

Water loss is increased by illness, activity, high altitude, high ambient temperature, and dry air. When more than 10% of body weight is lost without replacement, dehydration can become life threatening. If a child is vomiting and has diarrhea, water loss can be significant. Children who exercise strenuously, especially in a warm, dry environment, require additional water intake. After strenuous or prolonged exercise, however, high water intake without electrolyte replacement can lead to water intoxication.

Sodium

Sodium functions primarily to regulate extracellular fluid volume. It also regulates osmolarity, acid-base balance, and the membrane potential of cells and is involved in the cell membrane transport pump, exchanging with potassium in intracellular fluid. Sodium loss occurs with vomiting, diarrhea, and perspiration. Sodium requirements vary with the rate of extracellular fluid expansion, which is most rapid in infants and very young children. It is not necessary to add sodium to the diet, even for children who exercise and perspire heavily. In fact, the typical North American diet far exceeds minimum requirements for sodium intake, with most sodium coming from salt added during food processing and manufacturing. For children 1 to 3 years, 1000 mg per day is considered an adequate intake (AI) of sodium; for children 4 to 8 years, 1200 mg per day; and for children 9 to 18, 1500 mg per day (USDA and USDHHS, 2010).

Macronutrients

Protein

Protein is a fundamental component of all body cells. Dietary protein is broken down into amino acids, which are required for the synthesis of body cell protein and nitrogen-containing compounds, some enzyme and hormone activity, cell transport, and tissue growth and development. Ten “indispensable” or essential amino acids are not synthesized by the body and must be provided in the diet (phenylalanine, leucine, methionine, lysine, isoleucine, valine, threonine, tryptophan, histidine, and arginine [arginine is required in diet for infants but not adults]). Depending on their age, children should receive approximately 5% to 30% of daily calories from proteins (see Table 10-1).

Micronutrients

Vitamins

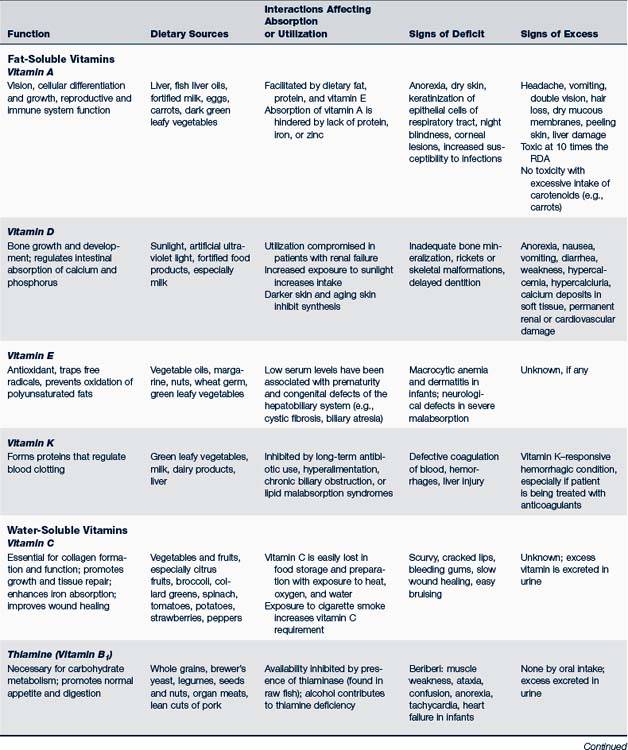

Recommendations for daily intake of fat- and water-soluble vitamins are listed in Table 10-1. Table 10-2 identifies specific metabolic functions, dietary sources, and signs of deficient or excessive intake of these vitamins.

Fat-Soluble Vitamins

• They can be stored for long periods of time in body tissues. As a result, temporary dietary deficiencies may not affect the body’s growth and development. If stores are depleted and nutritional intake is inadequate, signs of vitamin deficiency appear. If intake is excessive, as can occur when supplements are taken, toxic effects can appear.

• They are absorbed in the intestines along with fats and lipids in foods. Low-fat diets and increased intestinal motility or malabsorption syndromes may put individuals at risk for fat-soluble vitamin deficiency.

• They are fairly stable when heated, as in cooking. Food preparation does not destroy fat-soluble vitamins as readily as water-soluble vitamins.

• They require bile for absorption. Conditions that compromise the hepatobiliary system put the individual at risk for decreased vitamin absorption.

• They do not contain nitrogen and do not act as coenzymes in cellular metabolism of nutrients.

Water-Soluble Vitamins

In contrast to fat-soluble vitamins, water-soluble vitamins (C and B complexes) are stored in very small amounts in the body. If water-soluble vitamin intake is more than that needed by the body, absorption (primarily in the jejunum) decreases, and excess vitamins are excreted. As a result, daily intake of water-soluble vitamins is necessary, and there is little risk of toxicity from large doses. The B vitamins contain nitrogen and serve as essential coenzymes in the body’s metabolism of nutrients. Niacin (vitamin B3) plays a significant role in increasing high-density lipoproteins (HDLs).

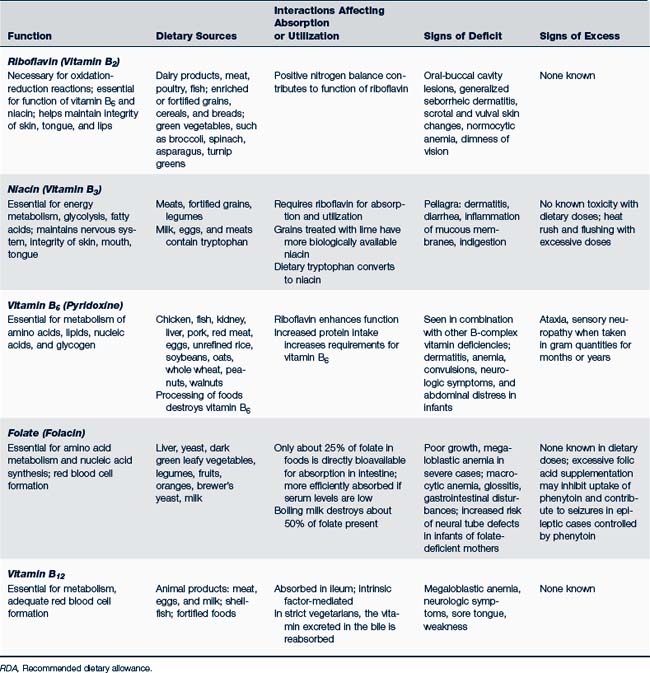

Minerals and Elements

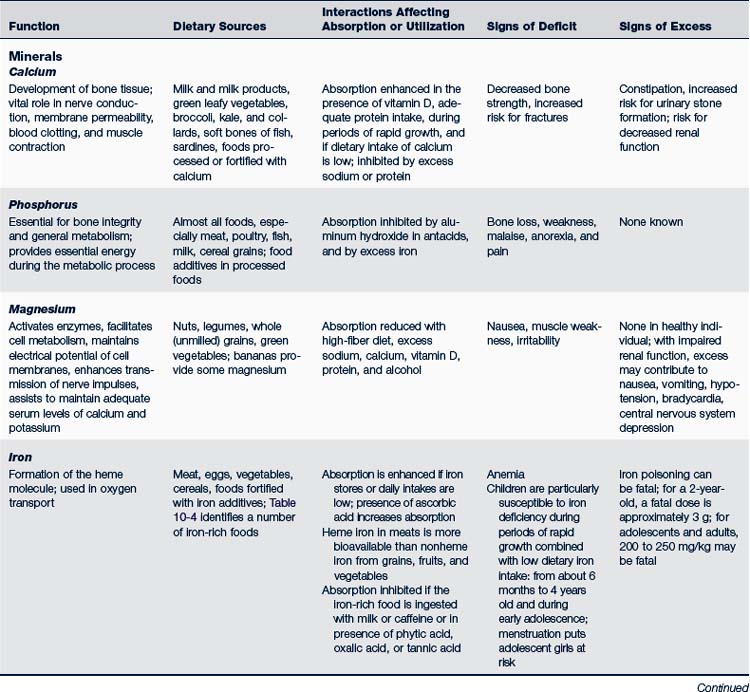

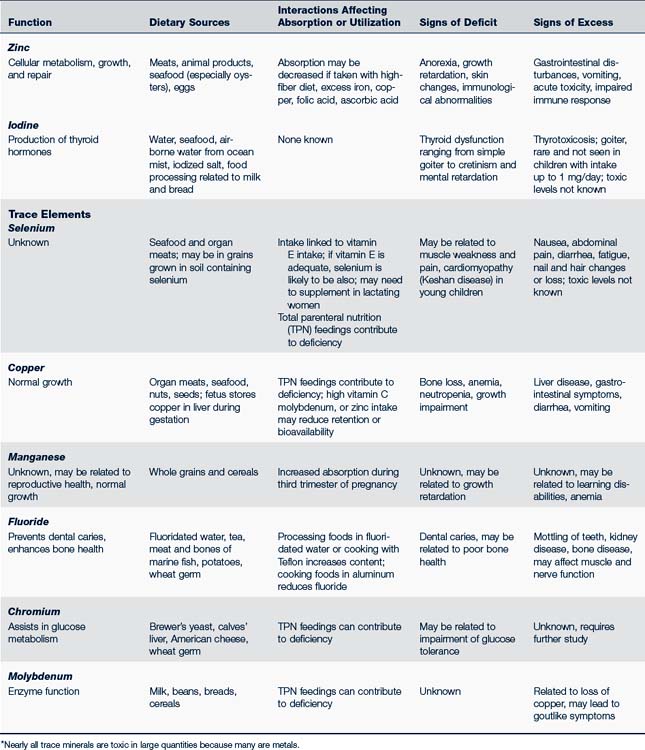

Three major minerals—calcium, magnesium, and phosphorus—are present in the body in amounts greater than 5 g. DRIs have been set for boron, calcium, chromium, copper, fluoride, iodine, iron, magnesium, manganese, molybdenum, nickel, phosphorus, selenium, silicon, vanadium, and zinc (FNB, 2005). Table 10-1 identifies recommended allowances for calcium, fluoride, iron, and zinc.

Peak bone density is directly related to calcium intake during the years of bone mineralization, primarily before 20 years of age. Bone calcification continues for several years more, however, so to ensure maximum peak bone density, dietary calcium needs to remain high until about 25 years old. Breastfed infants or those who are fed an approved infant formula receive sufficient calcium and should not be given a supplement. Minerals and essential trace elements, their functions, dietary sources, and signs of deficit or excess are presented in Table 10-3. Foods rich in iron are listed in Table 10-4.

TABLE 10-3 Minerals and Trace Elements: Function, Dietary Sources, Interactions, Deficiency, and Excess∗

Assessment of Nutritional Status

Assessment of Nutritional Status

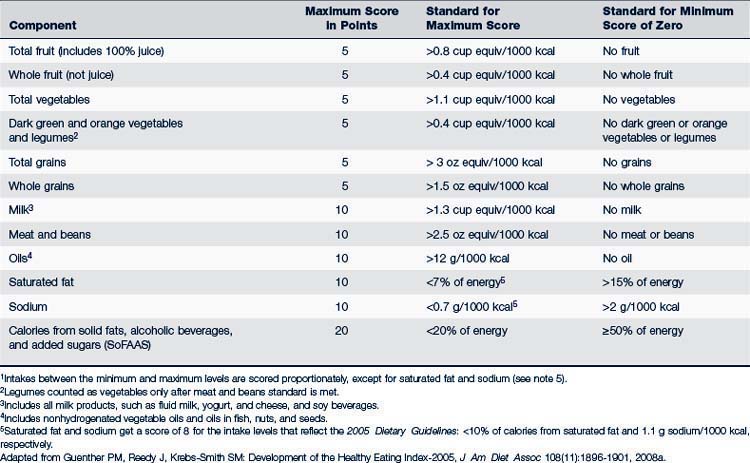

Much data can be collected in the intake interview, or using a 3-day diet recall. Providers can also use the Healthy Eating Index-2005 (HEI-2005) to assess quality of nutrient intake (Table 10-5). The HEI-2005 is based on 2005 Dietary Guidelines for Americans and the formerly used MyPyramid model and is a revision of previous Healthy Eating Indices. It lists 12 nutrient categories and gives each a score of 5, 10, or 20, with a maximum score of 100. The HEI-2005 does not require calculation of energy requirements, but measures nutrient units per 1000 kcal, an easier concept for families and children to understand and apply. To analyze individual diets, long-term intake should be assessed; a simple 24-hour recall does not adequately reflect the usual diet and can give a biased HEI number. Ideally a mean daily intake is examined over a period of time, often as long as 1 year. In population studies, HEI scores typically settle around 50 to 60, indicating significant nutritional deficit (Freedman et al, 2010; Guenther et al, 2008a,b).

History

Questions to elicit a history of nutritional status can be grouped into several categories:

• Nutritional status of mother during pregnancy

• Food and fluid intake of child and of family:

Type of feeding method used during infancy: If not breastfed, formula name and preparation. Any problems? When weaned? When solids started? Any allergies or intolerances noted?

Type of feeding method used during infancy: If not breastfed, formula name and preparation. Any problems? When weaned? When solids started? Any allergies or intolerances noted? Current nutritional intake of child (if child is still an infant, ask more specifically about frequency and amounts of feedings in a 24-hour period)

Current nutritional intake of child (if child is still an infant, ask more specifically about frequency and amounts of feedings in a 24-hour period) Amounts eaten (may use 24-hour recall, 3-day diet history, or length of time and frequency that child is at breast)

Amounts eaten (may use 24-hour recall, 3-day diet history, or length of time and frequency that child is at breast) Bottle feeding: Is bottle propped? Does child take bottle to bed at night or at naptime? Who feeds child?

Bottle feeding: Is bottle propped? Does child take bottle to bed at night or at naptime? Who feeds child? Breastfeeding: On demand or scheduled? How flexible is mother to demands of infant? Is mother working? Is breast milk frozen and fed by someone other than the mother?

Breastfeeding: On demand or scheduled? How flexible is mother to demands of infant? Is mother working? Is breast milk frozen and fed by someone other than the mother? Describe mealtimes: Does family sit down together? Are meals prepared at home? Does child eat at school? How often are “fast foods” eaten? What amount of time is spent eating? How long does it take to feed child?

Describe mealtimes: Does family sit down together? Are meals prepared at home? Does child eat at school? How often are “fast foods” eaten? What amount of time is spent eating? How long does it take to feed child?• Reactions to and attitudes about foods:

Cultural factors: What beliefs or attitudes does family have about how and what child should eat or how family should eat?

Cultural factors: What beliefs or attitudes does family have about how and what child should eat or how family should eat? Feeding abilities of child: For example, does child choke, gag, vomit, have suck or swallow difficulties, or refuse certain foods, perhaps because of texture or smell?

Feeding abilities of child: For example, does child choke, gag, vomit, have suck or swallow difficulties, or refuse certain foods, perhaps because of texture or smell?• Management of foods in the family:

Economic and environmental factors that influence how food is managed: For example, are finances adequate to supply nutritious foods? Is there a refrigerator? Does family have a car to carry larger amounts of food from store? Is there a full-service grocery store in the neighborhood? What is the socioeconomic status of family? Is food shopping budgeted? Are food stamps or other supplemental programs used?

Economic and environmental factors that influence how food is managed: For example, are finances adequate to supply nutritious foods? Is there a refrigerator? Does family have a car to carry larger amounts of food from store? Is there a full-service grocery store in the neighborhood? What is the socioeconomic status of family? Is food shopping budgeted? Are food stamps or other supplemental programs used?• Health status affected by nutrition:

Special considerations for children or family related to food: For example, does child have a chronic condition that requires a special diet, formula, or device for feeding? Are any medications being taken?

Special considerations for children or family related to food: For example, does child have a chronic condition that requires a special diet, formula, or device for feeding? Are any medications being taken? Growth, activity, and exercise pattern: For example, has child been growing as parent expects? Has there been a history of unusual weight gain or loss? Does child have energy to play? Is the child engaged in strenuous activity such as an athletic training program?

Growth, activity, and exercise pattern: For example, has child been growing as parent expects? Has there been a history of unusual weight gain or loss? Does child have energy to play? Is the child engaged in strenuous activity such as an athletic training program?Physical Examination

The physical examination should include the following:

• Height, weight, and head circumference measurements (see growth charts, Appendix B; also see table on inside cover of this text for average weight and height gains expected during childhood); arm circumference and triceps and subscapular skinfold caliper measurements for children at risk for obesity or malnutrition

• Skin condition (clear, smooth, firm, with good turgor)

• Muscle tone, posture, skeletal development (body erect, tone good)

• Hair (smooth, full, shiny; no dryness, broken ends, bare patches, or discoloration)

• Mucous membranes, eyes (moist, shiny, no dark circles, conjunctiva pink)

• Teeth (eruption appropriate to age, gums healthy, no bleeding)

• Neck (thyroid, parotid glands of normal size)

• Cardiovascular (no pathologic murmur; normal heart size; skin warm, pink, less than 3-second capillary refill; peripheral pulses equal, strong)

• Neurologic and behavior (alert, active, reflexes present, no complaints of headache, neuritis)

Management Strategies for Optimal Nutrition

Management Strategies for Optimal Nutrition

It is the providers’ responsibility to help parents and children make good decisions about nutrition and to facilitate families’ access to healthful foods. Providers may know what nutrients are necessary for healthy growth and development, but translating that information into day-to-day diet intake can be complex and confusing. What advice should be given to families when there is such a wide range of “normal” intake? What does it mean, for example, that 35% or less of energy requirements should be in the form of fats? Will it be harmful if a 3-month-old is introduced to commercially prepared fruits and vegetables? What, if any, are the benefits to eating organic foods? Should children avoid sugar or flavored milk? The questions are endless, and often without a clear answer. But the basic message providers should give parents is simple (Pollan, 2007):

• Eat food (versus processed, edible food-products that contain additives, fats, and few nutrients)

• Less of it (i.e., eat appropriate portions, do not overeat)

Nutritional Education

Age-Specific Considerations

Newborns and Infants

Infant Formulas

Breast milk is the ideal food for newborns and infants and should be promoted unless it is medically harmful to the infant. Most iron-fortified infant formulas provide adequate nutrition and, for some families, may be an appropriate alternative to breastfeeding. Box 10-1 outlines various types of commercial formulas available.

BOX 10-1 Categories of Infant Formulas∗

• Premature transitional formulas

• Nutrient-dense cow’s milk–based formulas

Similar to premature formula, but with less phosphorus and calcium; some preparations have up to 27 kcal/oz

Similar to premature formula, but with less phosphorus and calcium; some preparations have up to 27 kcal/oz• Formulas with long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids

More closely approximates human milk with content of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, an omega-3 fatty acid) and arachidonic acid (ARA, an omega-6 fatty acid)

More closely approximates human milk with content of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, an omega-3 fatty acid) and arachidonic acid (ARA, an omega-6 fatty acid) May enhance visual and mental development, especially in preterm infants (Fleith and Clandinin, 2005)

May enhance visual and mental development, especially in preterm infants (Fleith and Clandinin, 2005)• Formulas for feeding beyond 6 months of age (Step-2 formulas), usually calcium fortified, must be supplemented with solids

• Nutrient-dense formulas for older child

Higher caloric content (24-30 kcal/oz); nutrient dense; free amino acid and peptide-based formulas; lactose-free

Higher caloric content (24-30 kcal/oz); nutrient dense; free amino acid and peptide-based formulas; lactose-free• Nitrogen-free calorie supplements

Introduction of Solids

• Infants’ sucking patterns have changed sufficiently to allow mastery of chewing and swallowing.

• Infants can sit with some support, and they are able to purposefully move their heads.

• Infants are able to grasp, pick up, and bring objects to their mouths.

• Iron stores present at birth are being depleted.

• Growth demands require nutrients other than those provided in milk alone.

• Developmental needs (cognitive, sensory, and motor) are stimulated by new foods, textures, smells, tastes, and use of utensils.

Solids can be introduced in whatever sequence the family desires, often based on cultural or family customs, though nonallergenic cereals are usually the first infant foods. Dense proteins should be introduced later to allow for maturation of the renal system. Home-prepared foods, such as grains, mashed bananas, applesauce, pureed squash, cooked vegetables, and blenderized meats, can meet all the child’s nutritional needs. Although not necessary, commercial baby foods can provide adequate nutrition, but labels should be examined to determine their content, especially for calories, fats, additives, salt, and sugar. Box 10-2 lists some principles to keep in mind when beginning solids.

BOX 10-2 Principles for the Introduction of Solids into the Infant’s Diet

• Introduce one food at a time, waiting 3 to 5 days before offering another to assess for adverse reaction.

• Offer rice cereal, the least allergenic of cereal grains, as the first food.

• Introduce fruits, vegetables, and other cereals in any sequence desired.

• Feed only iron-fortified cereals.

• Prepare food appropriate to child’s developmental abilities (e.g., strained, mashed, or finger foods).

• Use home-prepared or commercially prepared foods.

Eating Habits

Parents should be counseled to respond promptly to a child’s feeding cues and to allow the child to initiate and guide the feeding interaction. Do not encourage the child to overeat. A selection of varied, healthful foods gives the older infant a chance to explore textures, smells, colors, and taste. Feeding is also a time when older infants and toddlers learn physical skills of fine motor control, cognitive skills of relationships between action and consequence (the dog will eat whatever is dropped on the floor), and skills of social exchange among family members.

Adolescents

Vitamin and Mineral Supplements

Thiamine, riboflavin, niacin, folate, iron, zinc, and calcium needs increase during adolescence (see Table 10-1). Most adolescents who eat a well-balanced diet need no supplements, but their irregular eating habits put them at risk for deficits. Adolescent girls are at risk for iron deficit when menstruation begins, and children who eat a vegan diet will need vitamin B12 supplements.

Pregnancy in Adolescence

When managing the pregnant teenager, providers should carefully assess dietary intake and counsel the adolescent to eat a varied and healthful diet. A prenatal multivitamin and mineral supplement, including iron, calcium, and folic acid, is essential. The pregnant teenager should strive for a total of 1300 to 1500 mg of calcium through diet and supplements each day (Chan et al, 2006). Daily folic acid intake of 0.4 mg is recommended for all girls capable of becoming pregnant, increased to 0.6 mg during pregnancy (FNB, 2005).

Strategies to Develop Healthy Eating Behaviors

Children Decide How Much of These Healthful Foods to Eat

Parents should be encouraged to provide the following:

• Positive examples of healthy intake; parents are the child’s role model

• An adequate supply of a wide variety of age-appropriate, nutritious foods and snacks

• Limits, but not prohibitions, on consumption of nonnutritious sugars and “sometimes” foods

• Food prepared in a form that stimulates children’s appetites

• Regular, structured mealtimes when the family sits down to eat together; this may occur only once a day

• A pleasant, relaxed environment for mealtimes

• Clear, developmentally appropriate expectations for children’s behavior at mealtimes

• Developmentally appropriate access to and instruction in the use of utensils

• Appropriate supervision during mealtimes

• Developmentally appropriate opportunities to participate in planning, preparing, and serving meals

The introduction of new foods can create tension between parents and children, with children refusing to try or rejecting new tastes or textures. Parents should be informed that this is a normal reaction for many children. Children may reject a food up to 15 to 20 times before they become accustomed to it and enjoy eating it, and parents should not be too concerned if a child rejects a particular food. Rather than force the child to try the new food or give in to the child’s feeding demands, the food should be removed without comment, then offered again at another meal. With a well-balanced diet, not eating a vegetable prepared at one meal, for example, will not compromise the child’s health. However, parents should be encouraged to avoid becoming the child’s “short-order cook,” preparing a special dish if the child rejects what has been fixed for the family. If a child chooses not to eat much at a particular meal, he or she will be hungrier at the next. Between meals, children should be offered age-appropriate snacks, but snacks should not be a substitute for meals; “grazing” or eating whenever food is available tends to override the child’s natural sense of satiety and encourage overeating (Brazelton and Sparrow, 2004).

• Offer the food when children are hungry.

• Allow children to taste a little of the food rather than eating a full portion.

• Expose children to the food by preparing and serving the food without expecting them to eat it.

• Provide an example of parents eating and enjoying the food.

• Prepare the food the way children prefer: few spices, lukewarm, recognizable.

• Associate food with pleasant experiences.

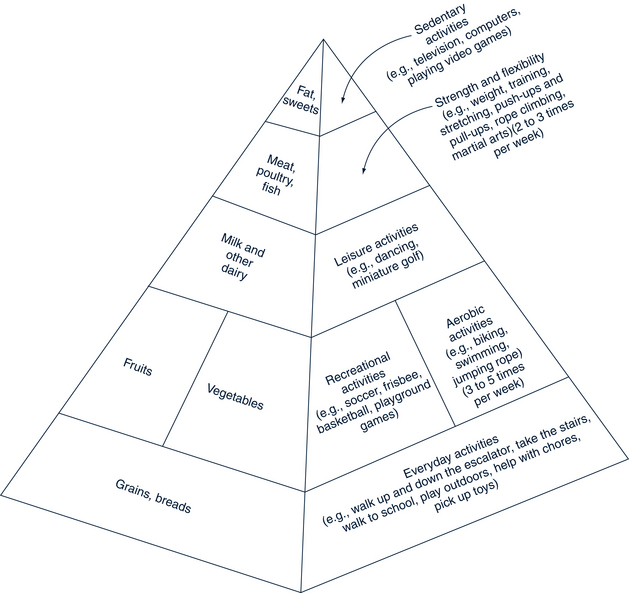

Physical Activity

Physical activity is integrally related to healthy nutrition. It is recommended that children and adolescents engage in 60 minutes of physical activity every day, most of which is moderate- or vigorous-intensity aerobic (exercise that makes them breathe hard); they should do vigorous activity at least 3 days a week and muscle- and bone-strengthening activity at least 3 days a week (USDHHS, 2009). Increased activity creates a demand for more calories and nutrients; more sedentary behavior means the body needs fewer calories, and sedentary lifestyles combined with poor eating habits can contribute to obesity. Figure 10-1 presents an integration of the food guide pyramid with a physical activity pyramid and can be used by providers to proactively counsel children about the importance of being active (see Chapter 13 for suggestions of activities).

FIGURE 10-1 Physical activity pyramid.

(Data from Reinhardt WC, Brevard PB: Integrating the food guide pyramid and physical activity pyramid for positive dietary and physical activity behaviors in adolescents, J Am Diet Assoc 102(3 Suppl):S96-S99, 2002; University of Missouri Extension: MyActivity Pyramid for Kids, 2007, Columbia, MO. Adapted from USDA MyPyramid. Available at www.extension.missouri.edu/explorepdf/hesguide/foodnut/00386.pdf [accessed May 11, 2011]).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree