Chapter 10 Nutrition

What Nutritional Issues Should I Discuss with Families?

Parents ask questions about breast-feeding, formula, food choices, the readiness of a child for new foods, the value of vitamin supplements, feeding behaviors, food allergy, and inadequate or excessive weight gain. To answer the questions, you need to know about the nutritional needs of human growth (see Chapter 8) and the child’s developmental capabilities at different ages (see Chapter 9). Be sure to ask about nutritional beliefs that guide family eating as well as ethnic, cultural, or health-related dietary issues. Inquire about family risk factors for early cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Obesity is the most prevalent nutritional disorder in the United States, so the weight of family members, eating habits, and growth patterns (including body mass index [BMI]) will be important information. Adults who have large waist circumference are at high risk for metabolic complications associated with obesity. Recent evidence supports a similar risk for children who have a waist circumference-to-height ratio (WC:Ht) > 0.50. In other words, keeping waist circumference below half of the height is an important message. Poor weight gain occasionally causes concern for an infant or young child, and parents will need guidance to improve nutrition. Toddlers present challenges because of behavior. Adolescents need nutritional advice for topics ranging from the high-calorie needs of athletes to the severely restricted diets of individuals with eating disorders. You must be prepared to discuss the risks of obesity and of fad diets with teenagers. Disease presents nutritional challenges for acute problems, such as gastroenteritis, and chronic diseases such as diabetes mellitus, inflammatory bowel disease, cystic fibrosis, celiac disease, and chronic kidney disease. Unsubstantiated “nutritional” information from the Internet often links food with disease and vague health problems. Your best response is to provide reliable sources of information such as the Web sites of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) or the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP).

INFANTS

How Are Newborns and Young Infants Fed?

Approximately 70% of U.S. mothers begin breast-feeding at birth, but most breast-fed infants are switched to formula before 6 months. Active encouragement of breast-feeding and support from clinicians, family, and friends, plus accommodations for lactating women in the workplace, will enhance the likelihood that a mother will choose to nurse her newborn and persist with breast-feeding until the infant is at least 6 months old. Mothers who choose to formula feed or cannot breast-feed also need support, plus information about appropriate formulas. In addition, most parents begin to diversify the diets for their infants by adding “baby foods” after ages 4 to 6 months and will need advice about appropriate foods. “Whole” cow milk is not appropriate for infants younger than 12 months because it often produces occult gastrointestinal bleeding and leads to iron deficiency anemia (Chapter 63). Cow milk also has excessive protein and poorly absorbed fat and iron.

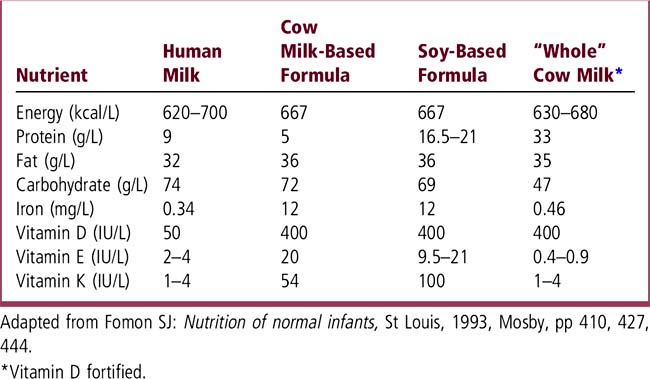

How Do Human Milk, Formulas, and Cow Milk Differ?

Table 10-1 provides a comparison of human milk, formulas, and whole cow milk. All have the same energy content, 20 kcal/oz (667 kcal/L), although human milk varies somewhat. See the nutritional formulary at your hospital or a resource such as The Harriet Lane Handbook for more detailed information. You can also find information about formulas designed to meet the needs of premature infants and infants with a variety of metabolic and nutritional disorders.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree