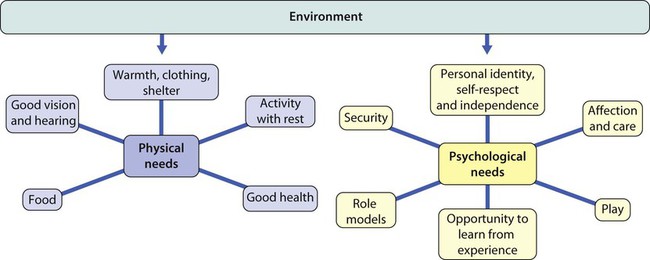

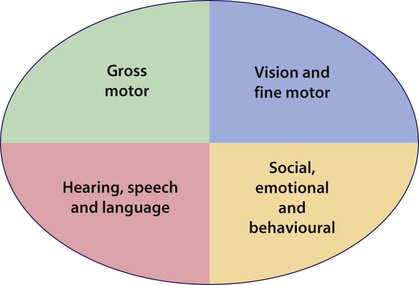

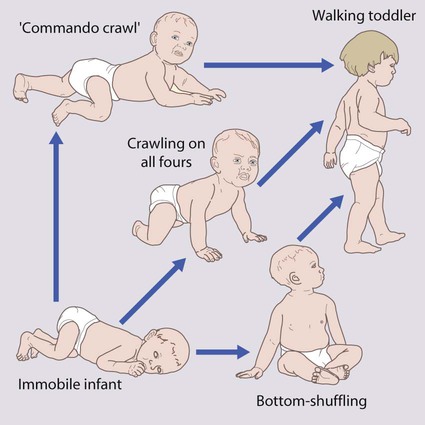

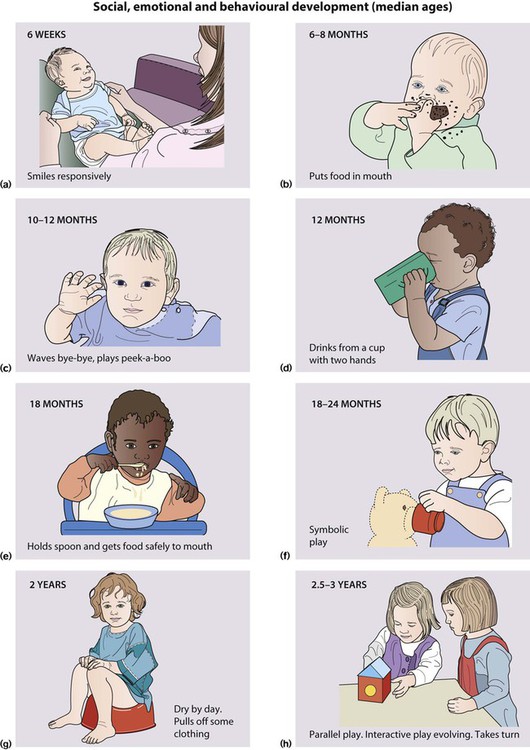

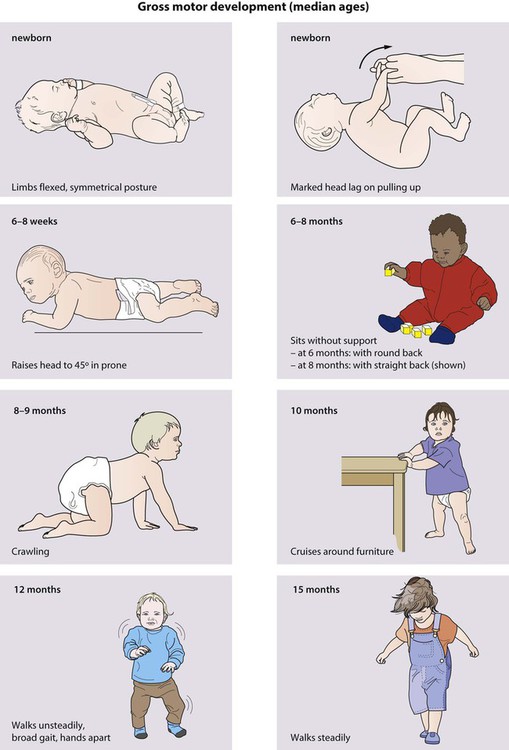

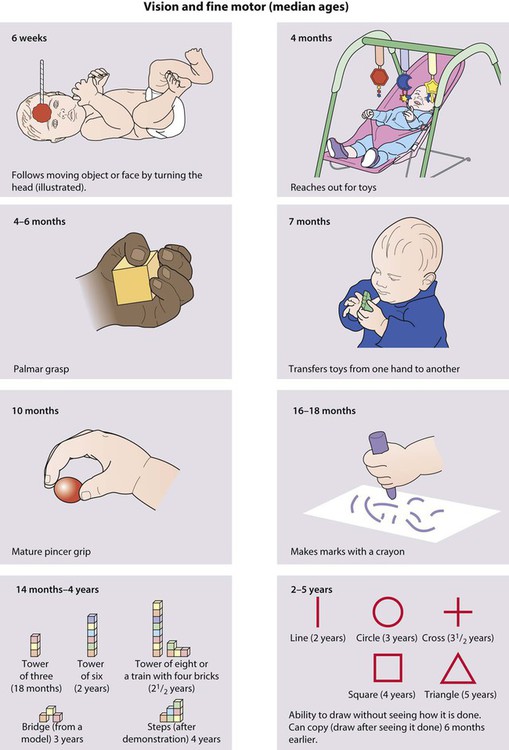

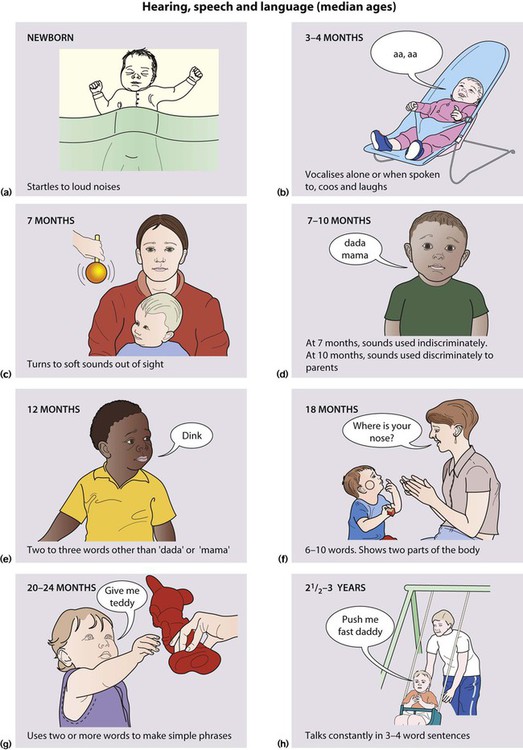

Normal development in the first few years of life is monitored: • by parents, who are provided with guidance about normal development in their child’s personal child health record and in a book Birth to Five, given to all parents in the UK • at regular child health surveillance checks • whenever a young child is seen by a healthcare professional, when a brief opportunistic overview is made. • help children achieve their maximum potential • provide treatment or therapy promptly (particularly important for impairment of hearing and vision) • act as an entry point for the care and management of the child with special needs. This chapter covers normal development. Delayed or abnormal development and the child with special needs are considered in Chapter 4. A child’s development represents the interaction of heredity and the environment on the developing brain. Heredity determines the potential of the child, while the environment influences the extent to which that potential is achieved. For optimal development, the environment has to meet the child’s physical and psychological needs (Fig. 3.1). These vary with age and stage of development: • Infants are totally physically dependent on their parents and require a limited number of carers to meet their psychological needs. • Primary school-age children can meet some of their physical needs and cope with many social relationships. • Adolescents are able to meet most of their physical needs while experiencing increasingly complex emotional needs. When considering developmental milestones: • The median age is the age when half of a standard population of children achieve that level; it serves as a guide to when stages of development are likely to be reached but does not tell us if the child’s skills are outside the normal range. • Limit ages are the age by which they should have been achieved. Limit ages are usually 2 standard deviations (SD) from the mean. They are more useful as a guide to whether a child’s development is normal than the median ages. Failure to meet them gives guidance for action regarding more detailed assessment, investigation or intervention. There is variation in the pattern of development between children. Taking motor development as an example, normal motor development is the progression from immobility to walking, but not all children do so in the same way. While most achieve mobility by crawling (83%), some bottom-shuffle and others crawl with their abdomen on the floor, so-called commando crawling (creeping) (Fig. 3.3). A very few just stand up and walk. The locomotor pattern (crawling, creeping, shuffling, just standing up) determines the age of sitting, standing and walking. When evaluating a child’s developmental progress and considering whether it is normal or not: • Concentrate on each field of development (gross motor; vision and fine motor; hearing, speech and language; social, emotional and behavioural) separately. • Consider the developmental pattern by thinking longitudinally and separately about each developmental field. Ask about the sequence of skills achieved as well as those skills to be anticipated shortly. • Determine the level the child has reached for each skill field. • Now relate the progress of each developmental field to the others. Is the child progressing at a similar rate through each skill field, or does one or more field of development lag behind the others? • Then relate the child’s developmental achievements to age (chronological or corrected). • Gross motor development (Fig. 3.4 and Table 3.1) Table 3.1 • Vision and fine motor (Fig. 3.5) • Hearing, speech and language (Fig. 3.6) • Social, emotional and behavioural (Fig. 3.7). • they are the centre of the world • inanimate objects are alive and have feelings and motives • events have a magical element • everything has a purpose. Toys and other objects are used in imaginative play as aids to thought, to help make sense of experience and social relationships.

Normal child development, hearing and vision

Influence of heredity and environment

Developmental milestones

Variation in the pattern of development

Is development normal?

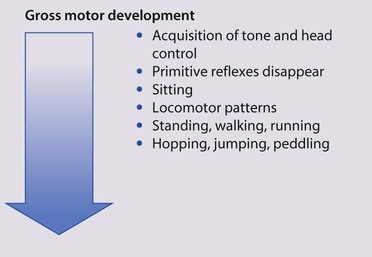

Pattern of child development

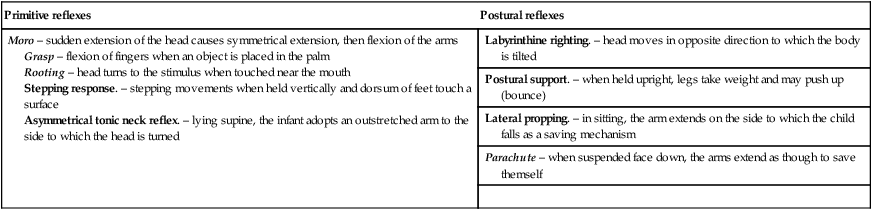

Primitive reflexes

Postural reflexes

Moro – sudden extension of the head causes symmetrical extension, then flexion of the arms

Grasp – flexion of fingers when an object is placed in the palm

Rooting – head turns to the stimulus when touched near the mouth

Stepping response. – stepping movements when held vertically and dorsum of feet touch a surface

Asymmetrical tonic neck reflex. – lying supine, the infant adopts an outstretched arm to the side to which the head is turned

Labyrinthine righting. – head moves in opposite direction to which the body is tilted

Postural support. – when held upright, legs take weight and may push up (bounce)

Lateral propping. – in sitting, the arm extends on the side to which the child falls as a saving mechanism

Parachute – when suspended face down, the arms extend as though to save themself

Cognitive development