CHAPTER 63 Non-HIV sexually transmitted infections

Introduction

World Health Organization (WHO) estimates suggest that more than 12 million new cases of syphilis, 62 million new cases of gonorrhoea, 92 million new cases of chlamydial infection and 174 million new cases of trichomoniasis occurred throughout the world in 1999 (World Health Organization 2001). Congenital syphilis, prevention of which is relatively easy and cost-effective, may still be responsible for as many as 14% of neonatal deaths. Up to 10% of women who are untreated, or inadequately treated, for chlamydial and gonococcal infections may become infertile as a consequence. On a global scale, up to 4000 newborn babies each year may become blind because of gonococcal and chlamydial ophthalmia neonatorum (note: ophthalmia neonatorum is a notifiable disease).

Epidemiology

WHO estimated that 340 million new cases of STIs occurred worldwide in 1999. The largest number of new infections occurred in South and South-east Asia, followed by sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean. However, the highest rate of new cases per 1000 population occurred in sub-Saharan Africa (World Health Organization 2001).

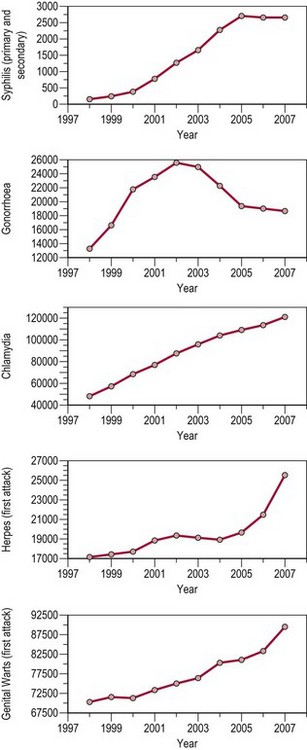

In the UK, peaks in STI diagnoses occurred in the mid-to-late 1940s (post World War II) and from the mid 1960s through to the early 1980s [from the age of sexual liberation to the advent of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)]. From 1998 to 2007, there was a substantial increase in diagnoses of most STIs (overall 6%). Cases of uncomplicated gonorrhoea increased by 42%, while chlamydia increased by 150%. Chlamydia has been the most commonly reported STI since 2001, overtaking genital warts (see Figure 63.1).

Figure 63.1 All new episodes of sexually transmitted infections seen in genitourinary medicine clinics 1998–2007.

Source: Health Protection Agency 2008 All new episodes seen at GUM clinics: 1998–2007. United Kingdom and country specific tables.

where Ro is the average number of new infections that result from one infection, β is transmissibility, c is the average rate of acquiring partners, and d is the duration of infection.

Screening

Recommendations 1 and 2: for key groups at risk of STIs

Recommendation 3: patients with an STI

Principles of Management of Sexually Transmitted Infections

History

Whilst in the UK, STIs are principally managed by specialist clinics (GUM), STIs also commonly present to the gynaecologist. The threshold at which the gynaecologist should take a sexual history is correspondingly low. The essentials are establishment of a rapport, privacy and confidence in the manner of questioning. Embarrassment on the part of the patient is quite understandable and should be dealt with empathetically. Phrases can be couched in terms such as ‘I am sorry to have to ask you this, please don’t be offended, it is important’. Essential elements of the sexual history, taken in combination with a general gynaecological and medical history, are shown in Box 63.1.

Specialist clinic tests

In the spirit of the NICE guidelines, time should be allocated to discuss modification of any high-risk activity to prevent reinfection (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence 2007). This should be non-judgmental and should be accompanied by written information on the subject to reinforce the message.

Genital Herpes

Clinical features

The first episode presents with multiple painful genital ulcers (see Figure 63.2). It is less severe in those with a history of oral herpes. Typical lesions begin as vesicles, at any or all sites from the introitus to the cervix, which become superficial tender ulcers with an erythematous halo and a yellow or grey base (Figure 63.3). Immunocompromised patients may have an atypical appearance which is an elongated ‘knife cut’ ulcer. There may be bilateral inguinal lymphadenopathy. Viral shedding continues until the lesions crust over. One-third of patients have systemic symptoms of fever and general malaise. Ten percent will experience viral meningitis with photophobia and headache. A few patients experience retention of urine, either because of pain due to passing urine over the lesions (in which case, micturating in a bath may help) or because of a viral autonomic neuritis. Involvement of other nerves may lead to hyperaesthetic buttocks, thighs or perineum for a time. Severe encephalitis is rare but may be seen more frequently in immunocompromised patients. Without treatment, the first episode lasts for 3–4 weeks.

Figure 63.2 Primary genital herpes: multiple painful ulcers are present.

From Bolognia J et al, Dermatology 2e, with permission of Elsevier.

Diagnosis

Serology

The differential diagnosis of vulval ulcers is shown in Table 63.1.

Table 63.1 The differential diagnosis of genital ulcers

| Infective | Non-infective |

|---|---|

| Herpes simplex virus | Aphthous ulcers |

| Primary syphilis | Trauma |

| Lymphogranuloma venereum | Skin disease (e.g. lichen sclerosis et atrophicus) Chancroid |

| Donovanosis | Behçet’s syndrome |

| Human immunodeficiency virus | Other multisystem disorder (e.g. sarcoidosis) |

| Dermatitis artefacta |

Treatment

Recurrent genital herpes

General advice includes saline bathing, Vaseline, analgesia and 5% lidocaine (lignocaine) ointment.

Syphilis

Clinical features

Primary syphilis

The incubation period after inoculation is 9–90 days (mean 21 days). The lesions may be extragenital and may be multiple. Chancres are usually painless, raised, well-circumscribed ulcers (Figure 63.4). There is a non-tender regional lymphadenopathy. The lesion may well go unnoticed, especially if it is intravaginal or rectal. It will heal spontaneously in 3–10 weeks.