126 Nevi

Clinical Manifestation And Management

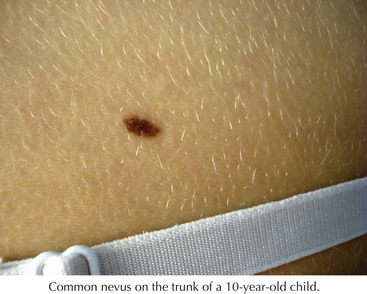

Common Acquired Melanocytic Nevi

Common nevi typically begin to develop in early childhood, and new nevi may continue to arise into the third decade (Figure 126-1). These lesions have a variety of presentations depending on where the nests of nevus cells reside, and they are named accordingly. Those with nevus cells at the dermal-epidermal junction are known as junctional nevi, and those with nevus cells in the dermis are intradermal nevi. Those with cells in both compartments are called compound. The shapes and sizes vary, but most are smaller than 6 mm in size. They are more common in sun-exposed areas, where increased sun exposure leads to more moles in these areas. In general, children with lighter pigmented skin have more nevi than those with darkly pigmented skin. Children with families with increased nevi also have more moles, suggesting a genetic component to the total number of lifetime moles acquired. Studies in first-degree relatives and twins suggest that genetic factors have a significant impact on the number of moles independent of skin color or sun exposure.

Dysplastic or Atypical Nevi

These are atypical nevi that have some asymmetry, size larger than 6 mm, variable color, and irregular borders (Figure 126-2). They frequently contain both a macular and papular component and variegated color (pink, brown, tan). They show architectural disorder histologically and are categorized by many pathologists as mildly, moderately, or severely atypical. Atypical moles typically begin to develop around puberty. The tendency to develop these nevi is genetic, with some families having multiple atypical nevi but no family history of melanoma but other families having both an increased risk of atypical moles and melanoma (familial atypical mole and melanoma syndrome [FAMM]).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree