- Polygenic (e.g. epilepsy, intelligence)

- Single gene defects (e.g. tuberous sclerosis)

- Chromosome abnormality (e.g. Down syndrome)

- Drugs (e.g. alcohol)

- Infections (e.g. rubella, HIV)

- Extreme prematurity

- Metabolic disturbances (e.g. hypoxia)

- Infections (e.g. meningitis)

- Trauma.

17.1 Seizures

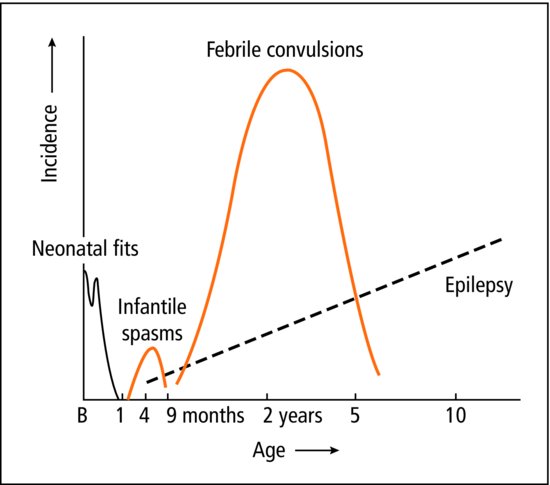

A seizure is the result of an abnormal paroxysmal discharge by cerebral neurones. The terms seizure, fit and convulsion are interchangeable. The pattern and prognosis varies with age (Figure 17.1). A seizure is a symptom, it has many potential causes and it may indicate epilepsy.

Fits are common in childhood

- 1 in 20 febrile convulsion

- 1 in 200 school age epilepsy

- 1 in 2000 severe epileptic disease.

17.1.1 Febrile convulsion

Febrile convulsion: a seizure without other known cause occurring between 6 months and 6 years of age with fever.

Febrile convulsion: a seizure without other known cause occurring between 6 months and 6 years of age with fever.Almost 5% of pre-school children have had a seizure; the most common cause by far is a febrile convulsion. A family history of febrile seizures is often present. They are precipitated by febrile illness and tend to occur at the start of the illness. Upper respiratory tract infections are the most common association. The seizures are generalized, with clonic movements usually lasting less than 5 min. There are no neurological signs after the seizure.

Temperature should be reduced to normal. Remove excess clothing or covers and in some tepid sponging is used. Paracetamol is usually given. Most commonly, shortly after the fit, the child appears well, while parents who thought their child might die may be desperately worried. One-third will have further febrile convulsions with future illnesses, but only 1–2% will develop epilepsy.

Management includes explanation of the relatively benign nature of febrile seizures. We need to make sure the family know about: recognition and management of fever (temperature control by removing clothing); future seizures (first aid, and when and how to seek emergency assistance). Antipyretics are not now recommended routinely (since they do not prevent further convulsions) but may be given to treat discomfort. Long-term prophylactic anticonvulsant therapy is occasionally used with recurrent febrile convulsions.

PRACTICE POINT

PRACTICE POINT17.1.2 The child with fits

Non-febrile seizure in a previously healthy child should prompt consideration of epilepsy. In between attacks, most children are perfectly well. It is exceptional for the doctor to have an opportunity to witness a fit, and the diagnosis rests principally on the history. A video on the parent’s phone can be very helpful.

PRACTICE POINT

PRACTICE POINTCareful examination and appropriate investigation are essential; the EEG is abnormal in 60%. Diagnosis can be difficult and it is important not to diagnose seizures without good reason. If the episodes are not typical, ask yourself ‘are these really fits?’ It is unusual for serious brain disease or metabolic abnormality to present solely with a fit in a child with no other neurological or developmental abnormality.

TREATMENT Management of fitting

TREATMENT Management of fitting- Call for help, this is a potentially serious situation

- Recovery position

- Semiprone with slight neck extension so that secretions drain out of the mouth.

- If respiratory distress

- Open the airways by gently extending the neck, lifting the jaw forward

- Do not put anything in the mouth

- Give O2 if available.

- Open the airways by gently extending the neck, lifting the jaw forward

- If fit continues >5 min, escalate up through these steps:

- Buccal midazolam or IV lorazepam (repeat after 10 mins if need)

- IV diazepam

- IV phenytoin (or if on phenytoin maintenance, phenobarbitone)

- Rectal paraldehyde

- Anaesthesia with thiopental and intensive care

- Buccal midazolam or IV lorazepam (repeat after 10 mins if need)

- Always check blood sugar

17.1.3 Epilepsy

Epilepsy is a common set of variable conditions with recurrent seizures.

Epilepsy is a common set of variable conditions with recurrent seizures.Epilepsy classification provides a helpful basis to approach therapy and support. Children with epilepsy should only be managed by a doctor trained to do so. The full classification is key in complex disease or where fits are hard to control. In infants and children there are 3 main axes of classification:

- Seizure type. This includes description of precipitating factors in reflex epilepsy.

- Epilepsy syndromes, patterns of disease with recognized characteristics. No single syndrome is common, but up to half of childhood epilepsy may be placed in a syndrome (e.g. West syndrome with infantile spasms; benign centrotemporal (Rolandic) epilepsy).

- Aetiology or cause. This includes genetic disease and importantly seizures symptomatic of other disease.

An additional axis describes impairment and relates to the impact of the condition on the child’s functioning, disability and health. The section below will focus on the main seizure types you should be able to recognize, but will not cover the other axes.

17.2 Seizure types

- Generalized

- tonic clonic

- absences

- myoclonic

- atonic

- infantile spasms

- tonic clonic

- Focal

- sensory

- motor

- with secondary generalization

- ± impaired consciousness

- sensory

- Precipitating factor

- e.g. flickering lights

17.2.1 Generalized seizures

17.2.1.1 Tonic–clonic

These fits comprise a tonic phase (continuous muscle spasm) which may start with a cry and, if prolonged, lead to cyanosis: then a clonic phase (jerking) which may be associated with tongue-biting and frothing at the mouth: then relaxation, unconsciousness and a period of drowsiness and/or confusion. Children often sleep after an attack. Recurrent episodes which are regularly followed by sleep suggest epilepsy. Most occur for no apparent reason. Flashing lights trigger fits in some children, usually when they are watching a malfunctioning TV screen or sitting very close to the TV. The EEG may show bilateral, slow-wave, subcortical seizure discharges. Major fits can last from less than 1 min to over 30 min (status epilepticus). Uncontrolled prolonged fits can cause hypoxia, and may lead to brain damage, especially in the temporal lobes.

17.2.1.2 Absences

Typical absence seizures (petit mal) begin in childhood. Most affected children are otherwise healthy with normal intelligence. An attack consists of a very brief absence of awareness lasting less than 5 s and accompanied by blinking. The eyes may roll up. The child does not fall down. He may present with school difficulties because of ‘daydreaming’ or inattention.

Absences may be provoked by encouraging the child to hyperventilate for 2 min. The characteristic EEG shows a three per second spike and wave pattern.

Atypical absence seizures tend to be longer, and associated with other movements, sensations or altered awareness of consciousness. The prognosis is less good than typical absences.

17.2.1.3 Myoclonic

The sudden brief jerks affect one part of the body, commonly an arm or leg. They are a common feature in children who have other neurological disorders. Single jerks as we fall asleep are normal (physiological myoclonus).

17.2.1.4 Atonic

Atonic (astatic) seizure are known as drop attacks. Sudden decrease in muscle tone makes a child lose postural control and drop to the floor.

17.2.1.5 Infantile spasms

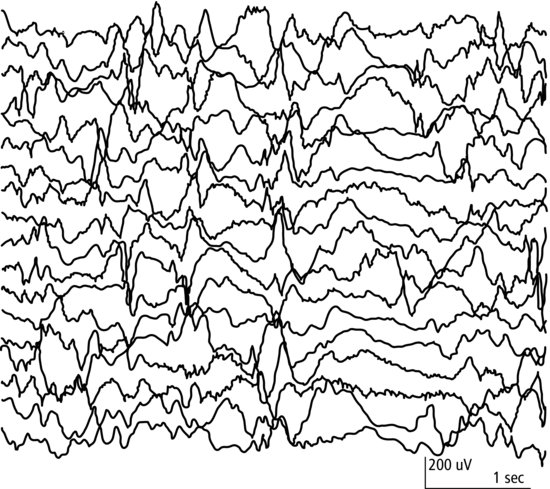

Infantile spasms are a rare and serious form of seizure usually at age 1–6 months. The infant doubles up, flexing at the waist and neck, and flinging the arms forward – a flexor spasm; less commonly it is an extensor spasm. Associated developmental delay is common. The EEG usually shows a characteristically disorganized picture – hypsarrhythmia (Figure 17.2). Anticonvulsants or corticosteroids may suppress the fits. The final outcome is related to the cause, which may be metabolic, malformation or cerebral damage. The single most common cause is tuberous sclerosis. Idiopathic infantile spasms is West syndrome.

17.2.2 Focal seizures

The seizure discharge starts in a focus in the brain. Sometimes the focus is at the site of previous cerebral damage. Focal (also known as partial) seizures may be motor (e.g. twitching of one limb), sensory (e.g. paraesthesia), autonomic (e.g. pallor) or psychic (e.g. strange thoughts or funny smells). Diagnostic problems are common and EEG and brain imaging are used.

Focal seizures may occur with or without loss of consciousness and awareness.

17.2.2.1 Temporal lobe epilepsy

Motor, sensory or emotional phenomena occur singly or in combination, together with impaired consciousness. These seizures vary widely in description, but in each child the pattern is usually the same each time. The diagnosis is confirmed by temporal lobe discharges on EEG.

17.2.2.2 Benign centrotemporal (Rolandic) epilepsy

Short focal fits, characteristically at night, affect the face or arms. School age children most commonly have a small number and the condition resolves. Frequent or numerous attacks may need treatment.

17.2.3 Neonatal seizures

Seizures are common in the first month as a result of birth injury, metabolic and infective causes or developmental abnormalities (Section 8.4.5).

17.2.4 General management of epilepsy

Epilepsy is the most common cause of childhood seizures, but it is important to search for a primary cause through careful history and examination. Seizures can be caused by space-occupying lesions, meningitis, hypoglycaemia, hypertension and many other factors.

Prophylactic anticonvulsant therapy is given to children with recurrent seizures, usually until the child has been fit-free for at least 2 years. The lowest dose of the safest drug that suppresses fits is used. The prognosis is good for children who are otherwise healthy, have a normal EEG and respond promptly to preventative therapy: less good for those with learning problems or cerebral palsy, with persistent seizure activity on EEG, and in whom a variety of drugs, alone or in combination, fail to give adequate control. Children’s epilepsy should be managed by team with appropriate expertise, often offering support through a specialist nurse.

TREATMENT Prophylactic anti-epileptic drugs (AED)

TREATMENT Prophylactic anti-epileptic drugs (AED)- Valproate–generalized (tonic–clonic, absence, myoclonic)

- Carbamazepine–focal and generalized (tonic–clonic, focal)

Most children with epilepsy attend normal school: it is important that teachers know how to recognize and deal with any seizure. Children should take part in most activities but may need extra supervision for swimming, and it may be wise to prevent them from doing activities such as fishing, rope or rock climbing, and canoeing. Some doctors forbid cycling in traffic if the child has had a seizure in the previous 2 years, though seizures are uncommon during concentrated activity.

RESOURCE

RESOURCE17.3 Conditions which may be mistaken for seizures

Many children have unusual periodic events as a result of other conditions (Table 17.1). A careful history from more than one observer should lead to an accurate diagnosis (Table 17.2).

Table 17.1 Other episodic events.

| Age 1–4 | Reflex anoxic seizures (brief cardiac asystole from vagal inhibition — pain) |

| Breath-holding attacks | |

| Gastro-oesophageal reflux, writhing or back arching | |

| Age 4–8 | Benign paroxysmal vertigo |

| Night terrors | |

| Age 9–16 | Faints |

| Migraine | |

| Habit spasms (tics) | |

| Behavioural disorders — psychosomatic |

Table 17.2 Features differentiating a seizure from a faint (syncope)

| Seizure | Faint | |

| Age | Any | 8–15 years |

| Timing | Day or night | Day |

| Situation | Commonly during inactivity | Standing (school assembly) |

| Prodrome | Brief (twitching, hallucinations, automatisms) | Long (dizziness, sweats, nausea) |

| Duration | Variable | Under 5 min |

| Tonic–clonic movement | Common | Rare |

| Colour change | May be cyanosis | Pallor |

| Injury (e.g. tongue-biting) | Common | Rare |

| Incontinent of urine | Common | Rare |

| After event | Drowsiness, confusion or headache | Quick full recovery |

| Rarely partial paralysis | Never paralysis |

17.3.1 Habit spasms (tics)

There may have been a reason for the movement initially – a twist of the neck in an uncomfortable collar, a forceful blink because of eyelid irritation – but the movement persists when the reason has gone. Reassurance that it is likely to improve with time, and a low-key supportive approach is usually all that is necessary.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree