27 Neurological Symptoms

We have scotch’d the snake, not kill’d it.

She’ll close and be herself, whilst our poor malice Remains in danger of her former tooth.

Neurological symptoms present particular difficulties for those working in pediatric palliative medicine. The evidence base for most symptom interventions derives largely from work done in adults. Historically, adult palliative medicine has largely addressed the needs of patients with cancer, while it is in the large group of children with non-cancer conditions that neurological symptoms occur most commonly.1 Typically, they are neurodegenerative conditions in which deterioration to death occurs over years or decades, and are characterized by severe neurological symptoms that may be difficult to treat.

General Principles

Multidimensional

In considering the impact of neurological symptoms, professionals need to consider not only their physical effects, but also their influence on psychosocial, emotional, and spiritual issues. In focusing on reducing the frequency of seizures, for example, professionals should not lose sight of the need to allow a child to engage meaningfully with his or her family. This can lead to the involvement of a potentially large and extended team with varying but, at times, over-lapping roles (Box 27-1).

BOX 27-1 The Interdisciplinary Team

Rational

In establishing that a given intervention is in the child’s best interest, it is clearly necessary to be aware of the existing evidence. In an age where evidence-based medicine is a professional requirement,2 it is important that practice is not just based on anecdotes and experience, but also is justified with research. Critical appraisal and clinical reasoning must underpin practice. Systematic reviews or meta-analyses, where they exist, are authoritative sources of such evidence. Individual carefully designed double-blind trials are also powerful evidence. Anecdote and case history, however, are not indicators of effectiveness. They are important signposts to studies that should take place, but should not result in an uncritical change of practice by themselves.

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) ap- proaches should be used in conjunction with conventional medicine to aim to provide better symptom control and meet the cultural, spiritual, and psychosocial needs of the child and family.3 Many neurological symptoms are exacerbated by depression, anxiety, and/or fatigue. There is evidence to suggest these are ameliorated by some CAM approaches, including massage,4–12 acupuncture,8,10,13–16 and transcutaneous electrical stimulation (TENS)8,17 can offer some assistance with this. The effectiveness of TENS is unclear18,19 but it is well tolerated by most patients. Music therapy and hydrotherapy are naturally enjoyable interventions for children (Fig. 27-1).

Symptoms

For a summary of doses and indications of medications in this chapter, see Table 27-1.

TABLE 27-1 Doses and Indications for Medications Mentioned in This Chapter

| Medication | Indication | Dosage |

|---|---|---|

| Midazolam | Status epilepticus and terminal seizure control. Breakthrough anxiety, such as panic attacks. Adjuvant for pain of cerebral irritation. Dyspnea | |

| Diamorphine | As for morphine. Useful where large doses need to be dissolved in small volume | Relative potency parenteral preparations 3x that of oral morphine. |

| Phenobarbital | Adjuvant in pain of cerebral irritation. Control of terminal seizures. Sedation | Child 1 mo-12 yrs, 1-1.5 mg/kg twice a day, increased by 2 mg/kg daily as required (usual maintenance dose 2.5-4 mg/kg once or twice a day) |

| Diazepam | Short-term anxiety relief. Relief of muscle spasm. Treatment of status epilepticus | |

| Levomepromazine | Antiemetic where cause is unclear, or where probably multifactorial. Secondary effects include sedation and analgesia | Analgesic: May be of benefit in a very distressed patient with severe pain unresponsive to other measures |

| Fentanyl | Severe pain (synthetic opioid analgesic), particularly as rotation from morphine or if patch formulation desirable | |

| Hydromorphone | Severe pain (opioid analgesic) especially if diamorphine unavailable and solubility is an issue | |

| Tizanidine | Muscle spasm | |

| Baclofen | Chronic severe spasticity of voluntary muscle | |

| Melatonin | Sleep disturbance caused by disruption of circadian rhythm (not anxiolytic) |

Seizures

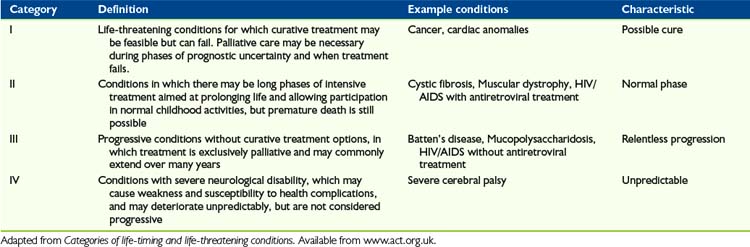

Children with life-limiting conditions in ACT categories III and IV (Table 27-2), which are often chronic neurological conditions, are likely to have seizures that have been difficult to control for some time. The result is typically that, at the time it is clear a palliative phase has been entered, children are on a large number of different anticonvulsants.

The solution to this is to use the buccal route. Small volumes of water soluble drugs such as midazolam and diamorphine can be administered between the cheek and the gum. They are absorbed rapidly through the oral mucosa, effectively providing an alternative parenteral route without needles. This is increasingly used for management of breakthrough seizures in neurology20 and is ideally suited to their management in the terminal phase.

Phenobarbital is rarely used in seizure disorders because of the risk of adverse effect in long-term use. In the palliative phase, however, where these are unlikely to be a significant consideration, it has a number of potential advantages over many other anticonvulsants, though not all are proved. It is anxiolytic, rather than simply sedative,21 effective against cerebral irritation; is sedating it may have some activity against neuropathic pain.22 It can also be given orally or through a gastrostomy tube.

It does, however, also have some disadvantages:

Midazolam is a short-acting benzodiazepine. It is often used by neurologists for breakthrough seizures, but rarely for background control because of its short half-life. In the palliative phase, Midazolam is usually given by continuous subcutaneous infusion although there is no reason in principle why it should not also be given intravenously. It can be mixed with other medications in the same syringe driver, including diamorphine, morphine, levomepromazine, and other medications commonly used in the final days of life. It is easy to titrate against symptoms due to its short half-life; 23 powerfully anxiolytic, amnestic and sedating; and has a broad range of anticonvulsant activity. Midazolam is widely used in pediatric palliative care, so it has reasonable clinical experience and evidence base. Also, it is highly soluble so can be given by buccal route.

Midazolam’s disadvantages are that paradoxical agitation can occur in some children24 and its short half-life makes it inappropriate for background control of seizures except by parenteral infusion. The drug can cause confusion; and in cognitively aware children, loss of memory may be a disadvantage, particularly if it impairs family relationships.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree