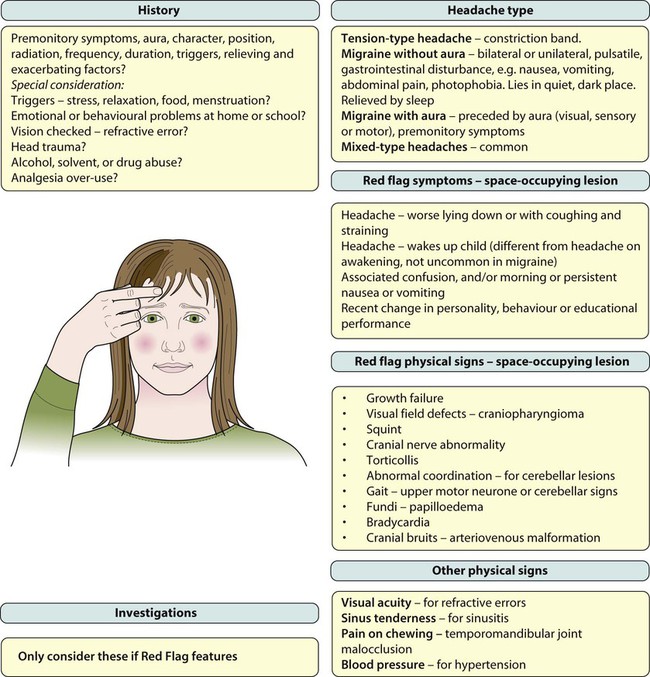

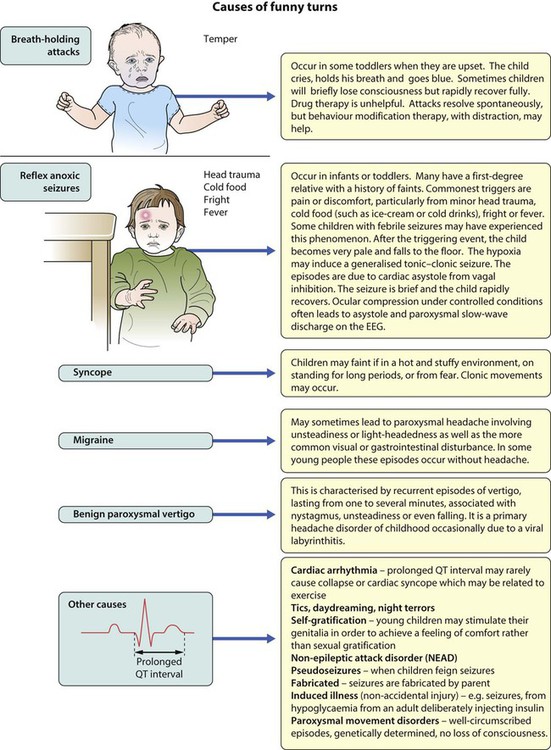

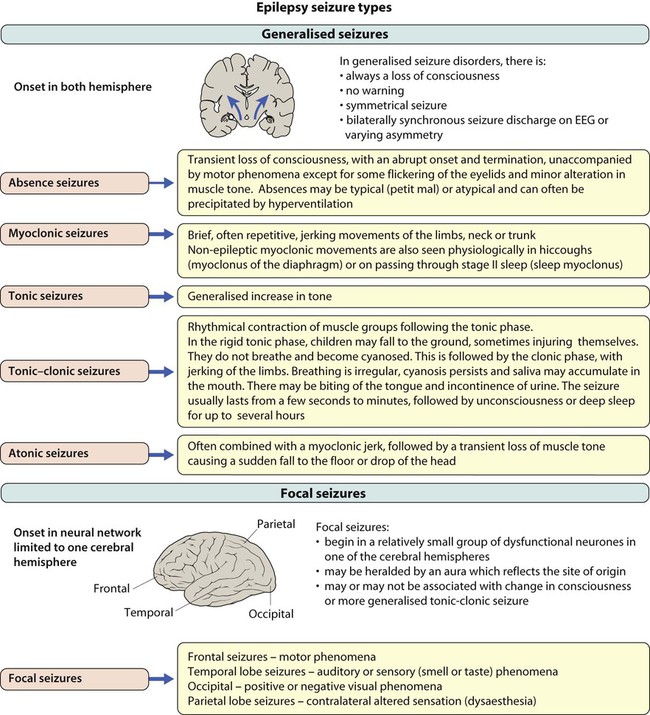

Headache is a frequent reason for older children and adolescents to consult a doctor. The International Headache Society (IHS) has devised a classification, as shown in Box 27.1, which defines: • Primary headaches: four main groups, comprising migraine, tension-type headache, cluster headache (and other trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias); and other primary headaches (such as cough or exertional headache). They are thought to be due to a primary malfunction of neurones. • Secondary headaches: symptomatic of some underlying pathology, e.g. from raised intracranial pressure and space-occupying lesions • Trigeminal and other cranial neuralgias, and other headaches including root pain from herpes zoster. The most common aura comprises visual disturbance, which may include: • Negative phenomena, such as hemianopia (loss of half the visual field) or scotoma (small areas of visual loss) • Positive phenomena such as fortification spectra (seeing zigzag lines). Rarely, there are unilateral sensory or motor symptoms. • Familial – linked to a calcium channel defect, dominantly inherited • Sporadic hemiplegic migraine • Basilar-type migraine – vomiting with nystagmus and/or cerebellar signs • Periodic syndromes – often precursors of migraine and include: – Cyclical vomiting – recurrent stereotyped episodes of vomiting and intense nausea associated with pallor and lethargy. The child is well in between. – Abdominal migraine – an idiopathic recurrent disorder characterised by episodic midline abdominal pain in bouts lasting 1–72 h. Pain is moderate to severe in intensity and associated with vasomotor symptoms, nausea and vomiting. The child is well in between episodes. – Benign paroxysmal vertigo of childhood – a heterogeneous disorder characterised by recurrent brief episodes of vertigo occurring without warning and resolving spontaneously in otherwise healthy children. Between episodes, neurological examination, audiometric and vestibular function tests are normal. • Visual field defects – from lesions pressing on the optic pathways, e.g. craniopharyngioma (a pituitary tumour) • Cranial nerve abnormalities causing diplopia, new-onset squint or facial nerve palsy. The VIth (abducens) cranial nerve has a long intracranial course and is often affected when there is raised pressure, resulting in a squint with diplopia and inability to abduct the eye beyond the midline. It is a false localising sign. Other nerves are affected depending on the site of lesion, e.g. pontine lesions may affect the VIIth (facial) cranial nerve and cause a facial nerve palsy • Torticollis (tilting of the head) • Growth failure, e.g. craniopharyngioma or hypothalamic lesion • Papilloedema – a late feature • Cranial bruits – may be heard in arteriovenous malformations but these lesions are rare. • Analgesia – paracetamol and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), taken as early as possible in an individual troublesome episode • Anti-emetics – prochlorperazine and metoclopramide • Serotonin (5-HT1) agonists, e.g. sumatriptan. A nasal preparation of this is licensed for use in children over 12 years of age. The causes of seizures are listed in Box 27.2. The acute management of seizures is described in Chapter 6. Examination should focus on the cause of the fever, which is usually a viral illness, but a bacterial infection including meningitis should always be considered. The classical features of meningitis such as neck stiffness and photophobia may not be as apparent in children <18 months of age, so an infection screen (including blood cultures, urine culture and lumbar puncture for CSF) may be necessary. If the child is unconscious or has cardiovascular instability, lumbar puncture is contraindicated and antibiotics should be started immediately. There is a broad differential diagnosis for children with paroxysmal disorders (‘funny turns’). Epilepsy is a clinical diagnosis based on the history from eyewitnesses and the child’s own account. If available, videos of the seizures or suspected seizures can be of great help. The diagnostic question is whether the paroxysmal events are that of an epilepsy of childhood or one of the many conditions which mimic it (Fig. 27.1). The most common pitfall is that of syncope leading to an anoxic (non-epileptic) tonic-clonic seizure. Epilepsy has an incidence of about 0.05% (after the first year of life when it is even more common) and a prevalence of 0.5%. This means that most large secondary schools will have about six children with an epilepsy. Epilepsy is a chronic neurological disorder characterised by recurrent unprovoked seizures, consisting of transient signs and/or symptoms associated with abnormal, excessive or synchronous neuronal activity in the brain. Most epilepsy is idiopathic but other causes of seizures are listed in Box 27.2. • Generalised – discharge arises from both hemispheres. They may be – absence, myoclonic, tonic, tonic-clonic and atonic • Focal – where seizures arise from one or part of one hemisphere. Focal seizure manifestations will depend on the part of the brain where the discharge originates: • Frontal seizures – involve the motor or premotor cortex. May lead to clonic movements, which may travel proximally (Jacksonian march). Asymmetrical tonic seizures can be seen, which may be bizarre and hyperkinetic and can be mistakenly dismissed as non-epileptic events. Atonic seizures may arise from mesial frontal discharge. • Temporal lobe seizures, the most common of all the epilepsies – may result in strange warning feelings or aura with smell and taste abnormalities and distortions of sound and shape. Lip-smacking, plucking at one’s clothing and walking in a non-purposeful manner (automatisms) may be seen, following spread to the pre-motor cortex. Déjà-vu and jamais-vu are described (intense feelings of having been, or never having been, in the same situation before). Consciousness can be impaired and the length of event is longer than a typical absence. • Occipital seizures – cause distortion of vision. • Parietal lobe seizures – cause contralateral dysaesthesias (altered sensation), or distorted body image. The main seizure types are summarised in Figure 27.2 and the epilepsy syndromes in Table 27.1. Table 27.1 Some epilepsy syndromes – arranged by age of onset *Although called benign, may be specific learning difficulties in some children. • Structural. MRI and CT brain scans are not required routinely for childhood generalised epilepsies. They are indicated if there are neurological signs between seizures, or if seizures are focal, in order to identify a tumour, vascular lesion, or area of sclerosis which could be treatable. MRI FLAIR (fluid-attenuated inversion recovery) sequences better detect mesial temporal sclerosis in temporal lobe epilepsy. • Functional scans. While it is not always possible to see structural lesions, techniques have advanced to allow functional imaging to detect areas of abnormal metabolism suggestive of seizure foci. These include PET (positron emission tomography) and SPECT (single positron emission computed tomography), which use isotopes and ligands, injected and taken up by metabolically active cells. Both can be used between seizures to detect areas of hypometabolism in epileptogenic lesions. SPECT can also be used to capture seizures and areas of hypermetabolism. Functional MRI can be used alongside psychological testing –including memory assessment – to minimise the risk of postoperative impairment. • Not all seizures require AED therapy. This decision should be based on the seizure type, frequency and the social and educational consequences of the seizures set against the possibility of unwanted effects of the drugs. • Choose the appropriate drug for the seizure. Inappropriate AEDs may be detrimental, e.g. carbamazepine can make absence and myoclonic seizures worse. • Monotherapy at the minimum dosage is the desired goal, although in practice more then one drug may be required. • All AEDs have potential unwanted effects and these should be discussed with the child and parent. • Drug levels are not measured routinely, but may be useful to check for adherence to advice or with some drugs with erratic pharmacokinetics, e.g. phenytoin. • Children with prolonged seizures are given rescue therapy to keep with them. This is usually a benzodiazepine, e.g. rectal diazepam or buccal midazolam. • AED therapy can usually be discontinued after 2 years free of seizures. Guidance regarding treatment options for different seizure types are shown in Table 27.2. Common unwanted effects of AEDs are shown in Table 27.3. Table 27.2 Choice of anti-epileptic drugs (NICE 2004) Table 27.3 Common or important unwanted effects of anti-epileptic drugs

Neurological disorders

Headache

Primary headaches

Tension-type headache

Migraine with aura

Uncommon forms of migraine

Secondary headaches

Raised intracranial pressure and space-occupying lesions

Management

Rescue treatments

Seizures

Febrile seizures

Paroxysmal disorders

Epilepsies of childhood

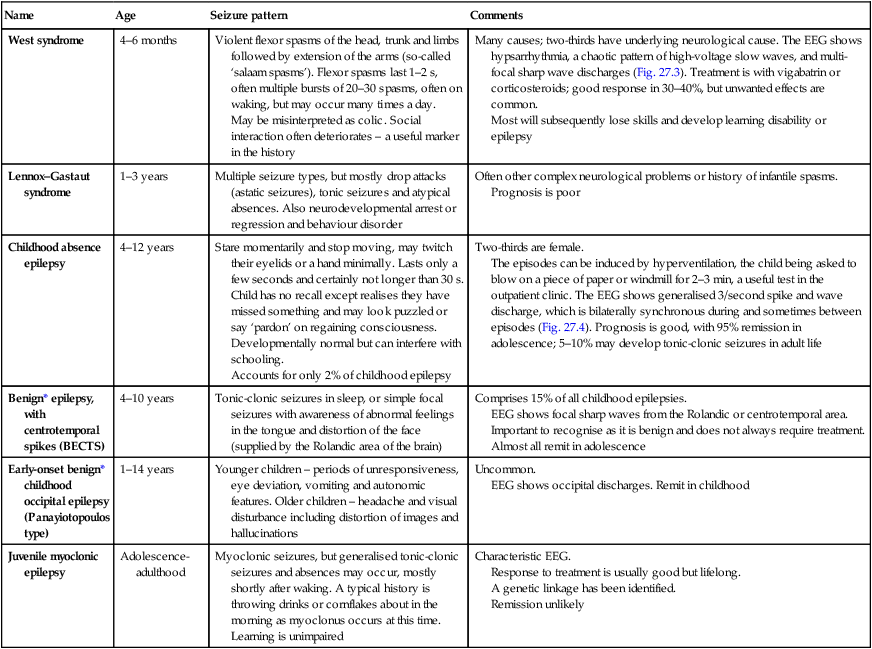

Name

Age

Seizure pattern

Comments

West syndrome

4–6 months

Violent flexor spasms of the head, trunk and limbs followed by extension of the arms (so-called ‘salaam spasms’). Flexor spasms last 1–2 s, often multiple bursts of 20–30 spasms, often on waking, but may occur many times a day.

May be misinterpreted as colic. Social interaction often deteriorates – a useful marker in the history

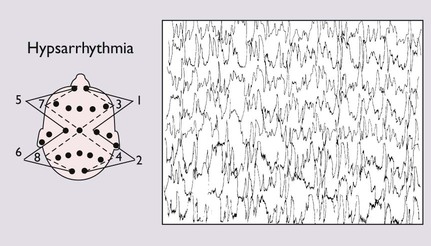

Many causes; two-thirds have underlying neurological cause. The EEG shows hypsarrhythmia, a chaotic pattern of high-voltage slow waves, and multi-focal sharp wave discharges (Fig. 27.3). Treatment is with vigabatrin or corticosteroids; good response in 30–40%, but unwanted effects are common.

Most will subsequently lose skills and develop learning disability or epilepsy

Lennox–Gastaut syndrome

1–3 years

Multiple seizure types, but mostly drop attacks (astatic seizures), tonic seizures and atypical absences. Also neurodevelopmental arrest or regression and behaviour disorder

Often other complex neurological problems or history of infantile spasms.

Prognosis is poor

Childhood absence epilepsy

4–12 years

Stare momentarily and stop moving, may twitch their eyelids or a hand minimally. Lasts only a few seconds and certainly not longer than 30 s. Child has no recall except realises they have missed something and may look puzzled or say ‘pardon’ on regaining consciousness.

Developmentally normal but can interfere with schooling.

Accounts for only 2% of childhood epilepsy

Two-thirds are female.

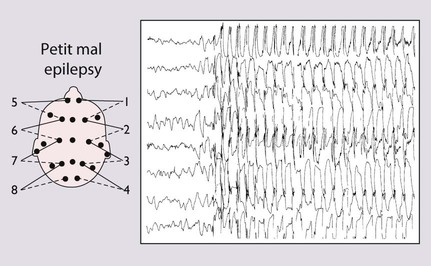

The episodes can be induced by hyperventilation, the child being asked to blow on a piece of paper or windmill for 2–3 min, a useful test in the outpatient clinic. The EEG shows generalised 3/second spike and wave discharge, which is bilaterally synchronous during and sometimes between episodes (Fig. 27.4). Prognosis is good, with 95% remission in adolescence; 5–10% may develop tonic-clonic seizures in adult life

Benign* epilepsy, with centrotemporal spikes (BECTS)

4–10 years

Tonic-clonic seizures in sleep, or simple focal seizures with awareness of abnormal feelings in the tongue and distortion of the face (supplied by the Rolandic area of the brain)

Comprises 15% of all childhood epilepsies.

EEG shows focal sharp waves from the Rolandic or centrotemporal area. Important to recognise as it is benign and does not always require treatment. Almost all remit in adolescence

Early-onset benign* childhood occipital epilepsy (Panayiotopoulos type)

1–14 years

Younger children – periods of unresponsiveness, eye deviation, vomiting and autonomic features. Older children – headache and visual disturbance including distortion of images and hallucinations

Uncommon.

EEG shows occipital discharges. Remit in childhood

Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy

Adolescence-adulthood

Myoclonic seizures, but generalised tonic-clonic seizures and absences may occur, mostly shortly after waking. A typical history is throwing drinks or cornflakes about in the morning as myoclonus occurs at this time. Learning is unimpaired

Characteristic EEG.

Response to treatment is usually good but lifelong.

A genetic linkage has been identified.

Remission unlikely

Investigation of seizures

Imaging

Management

Anti-epileptic drug (AED) therapy

Seizure type

First-line

Second-line

Generalised seizures

Tonic-clonic

Valproate, carbamazepine

Lamotrigine, topiramate

Absence

Valproate, ethosuximide

Lamotrigine

Myoclonic

Valproate

Lamotrigine

Focal seizures

Carbamazepine, valproate

Lamotrigine shown since to be most effective – but slow titration

Topiramate, levetiracetam, oxcarbazepine, gabapentin, tiagabine, vigabatrin

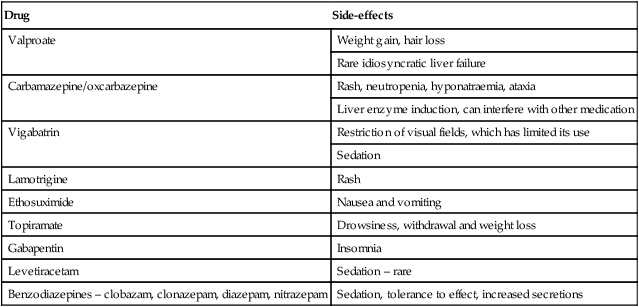

Drug

Side-effects

Valproate

Weight gain, hair loss

Rare idiosyncratic liver failure

Carbamazepine/oxcarbazepine

Rash, neutropenia, hyponatraemia, ataxia

Liver enzyme induction, can interfere with other medication

Vigabatrin

Restriction of visual fields, which has limited its use

Sedation

Lamotrigine

Rash

Ethosuximide

Nausea and vomiting

Topiramate

Drowsiness, withdrawal and weight loss

Gabapentin

Insomnia

Levetiracetam

Sedation – rare

Benzodiazepines – clobazam, clonazepam, diazepam, nitrazepam

Sedation, tolerance to effect, increased secretions

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree