Chapter 63 Neurologic Emergencies and Stabilization

Neurocritical Care Principles

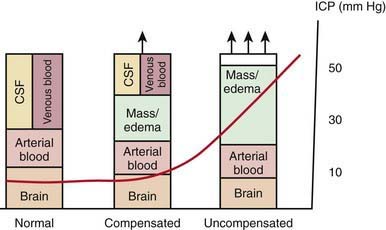

Increases in intracranial volume can result from swelling, masses, or increases in blood and CSF volumes. As these volumes increase, compensatory mechanisms decrease ICP by (1) decreasing CSF volume (CSF is displaced into the spinal canal or absorbed by arachnoid villi), (2) decreasing cerebral blood volume (venous blood return to the thorax is augmented), and/or (3) increasing cranial volume (sutures pathologically expand or bone is remodeled). Once compensatory mechanisms are exhausted (the increase in cranial volume is too large), small increases in volume lead to large increases in ICP or intracranial hypertension (Fig. 63-1). As ICP continues to increase, brain ischemia can occur as CPP falls. Further increases in ICP can ultimately displace the brain downward into the foramen magnum—a process called cerebral herniation, which can become irreversible in minutes and may lead to severe disability or death.

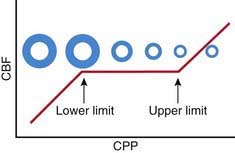

Oxygen and glucose are required by brain cells for normal functioning, and these nutrients must be constantly supplied by cerebral blood flow (CBF). Normally, CBF is constant over a wide range of blood pressures (blood pressure autoregulation of CBF) via actions mainly within the cerebral arterioles. Cerebral arterioles are maximally dilated at lower blood pressures and maximally constricted at higher pressures so that CBF does not vary during normal fluctuations (Fig. 63-2). Acid-base balance of the CSF (often reflected by acute changes in PaCO2), body/brain temperature, glucose utilization, and other vasoactive mediators (i.e., adenosine, nitric oxide) can also affect the cerebral vasculature.

Attention to detail and constant reassessment are paramount in managing children with critical neurologic insults. Among the most valuable tools for serial, objective assessments of neurologic condition is the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) (see Table 62-3). Originally developed to assess level of consciousness after traumatic brain injury (TBI) in adults, the GCS is also valuable in pediatrics. Modifications to the GCS have been made for nonverbal children and are available for infants and toddlers (see Table 62-3). Serial assessments of the GCS score along with a focused neurologic examination are invaluable to detection of injuries before permanent damage occurs in the vulnerable brain.

Traumatic Brain Injury

Laboratory Findings

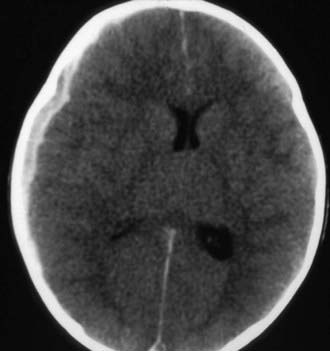

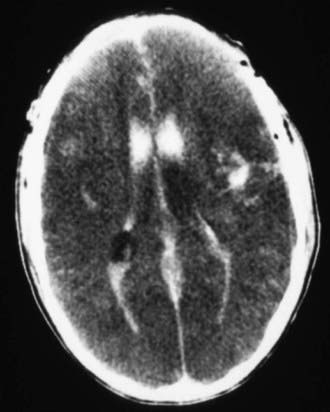

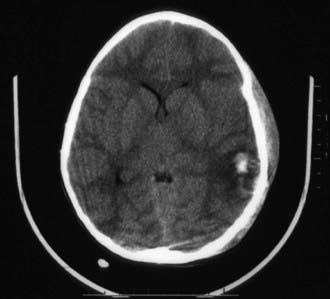

Cranial CT should be obtained immediately after stabilization (Figs. 63-3 to 63-11). Generally, other laboratory findings are normal in isolated TBI, although occasionally coagulopathy or the development of the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH) or, rarely, cerebral salt wasting is seen. In the setting of TBI with polytrauma, other injuries can result in laboratory abnormalities, and a full trauma survey is important in all patients with severe TBI (Chapter 66).

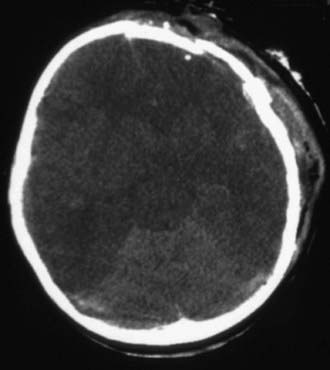

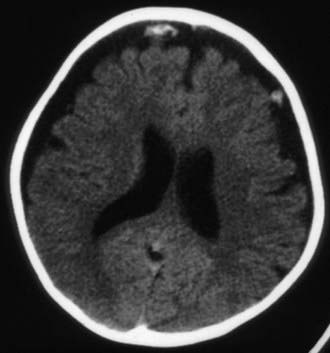

Figure 63-3 Abusive head trauma in an infant. Note the subdural fluid collections, dilated ventricles, and blood.

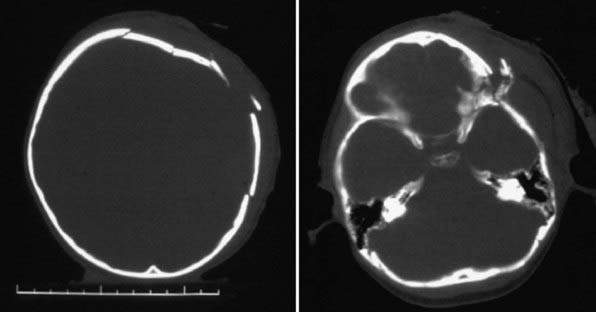

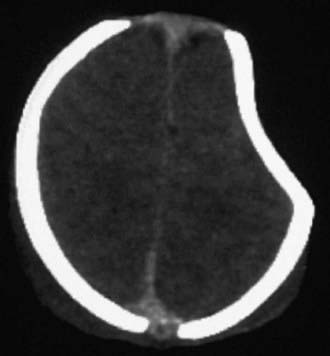

Figure 63-7 A depressed skull fracture due to traumatic delivery with forceps. Brain swelling can be seen.

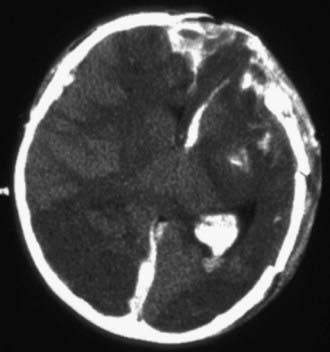

Figure 63-10 Severe traumatic brain injury with multiple depressed skull fractures and intraparenchymal hemorrhage.

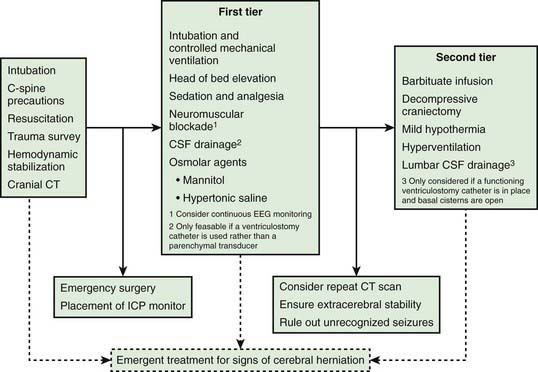

Treatment

Infants and children with severe or moderate TBI (GCS score 3-8 or 9-12, respectively) receive intensive care unit (ICU) monitoring. Evidence-based guidelines for management of severe TBI have been published (Fig. 63-12). This approach to ICP-directed therapy is also reasonable for other conditions in which ICP is monitored. Care involves a multidisciplinary team comprising pediatric caregivers from neurologic surgery, critical care medicine, surgery, and rehabilitation, and is directed at preventing secondary insults and managing raised ICP. Initial stabilization of infants and children with severe TBI includes rapid sequence tracheal intubation with spine precautions along with maintenance of normal extracerebral hemodynamics, including blood gas values (PaO2, PaCO2), MAP, and temperature. Intravenous fluid boluses may be required to treat hypotension. Euvolemia is the target, and hypotonic fluids should be rigorously avoided; normal saline is the fluid of choice. Pressors may be needed as guided by monitoring of central venous pressure (CVP), with avoidance of both fluid overload and exacerbation of brain edema. A trauma survey should be performed. Once stabilized, the patient should be taken for CT scanning to rule out the need for emergency neurosurgical intervention. If surgery is not required, an ICP monitor should be inserted to guide the treatment of intracranial hypertension.