10 Neurologic Emergencies

Status Epilepticus

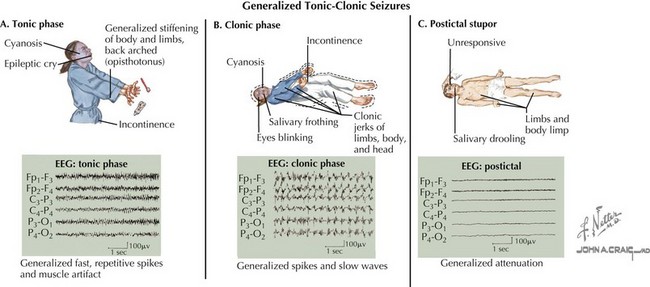

A seizure is defined as a transient, involuntary alteration of consciousness, behavior, motor activity, sensation, or autonomic function as a result of hypersynchrony and increased rate of cerebral neural discharges (Figure 10-1). Between 3% and 6% of children have at least one seizure in the first 16 years of life. Many seizures are associated with fever. Seizures can occur in individuals with underlying tendencies to seize (i.e., epilepsy) or secondary to other processes that primarily or secondarily affect the central nervous system. Seizures are discussed in detail in Chapter 74.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Common to the pathophysiology of all seizures is the hypersynchrony of neuronal discharges. The inciting cause varies and may include metabolic, anatomic, infectious, and primary neurologic processes (see Chapter 74). Uncovering the cause of SE is essential because it guides subsequent evaluation and management of a patient in SE.

Clinical Presentation

History

A brief, focused history should be obtained in the initial evaluation of a seizing patient with the goal of uncovering the precipitating event(s). Important historical features to obtain include recent head trauma, illnesses, fever, exposure to toxins, and current medications. It is important to know if the patient has epilepsy or has seized before, and if so, what antiseizure medications are prescribed, adherence to this regimen, and recent changes to the treatment regimen. Finally, it is important to know what medications, if any, have been given to stop the current seizure. It is important to know whether the seizure is associated with fever because febrile seizures are unique to children 6 months to 6 years of age and may be evaluated and treated differently than seizures not associated with fever (see Chapter 74).

Physical Examination

Other than seizure type, the physical examination in a child in SE should focus on eliciting the cause of the seizure. Fever may be a sign of infection. Meningismus and a toxic appearance can be suggestive of meningitis. A toxidrome may lead the clinician to look for potential toxic ingestions (see Chapter 9). Significant hypertension implies hypertensive encephalopathy. Although a complete neurologic examination is difficult in a seizing patient, focal neurologic signs can suggest intracranial or spinal lesions. The entire body should be examined for signs of trauma. Dysmorphic features may be associated with nervous system abnormalities.

Differential Diagnosis

There are other paroxysmal events that can mimic seizures in children that must be considered in the differential diagnosis. Breath-holding spells occur in children 6 months to 4 years of age and consist of a period of crying resulting from an inciting event, such as trauma, followed by breath holding and ensuing pallor or cyanosis. The child becomes rigid and may have twitching movements but quickly returns to a full level of alertness. Syncope, a brief loss of consciousness and muscle tone, can be differentiated from seizure by history and physical examination (see Chapter 48). Sleep disorders, such as night terrors, benign myoclonus, and sleep paralysis, can mimic seizures.

Evaluation and Management

Benzodiazepines are the first-line anticonvulsant medications for treating children with SE (Table 10-1). IV lorazepam is usually preferred, but if IV access is not available, midazolam can be given via the buccal or intramuscular route or diazepam can be administered rectally. Although these agents have similarly rapid onsets of action, lorazepam lasts much longer than other benzodiazepines (≤12-24 hours). As a result, one must be mindful to administer another agent for long-term seizure control when using other benzodiazepines as a first-line agent. If the patient does not have seizure remittance after benzodiazepine administration, phenytoin (or fosphenytoin) is widely considered the next anticonvulsant agents to use. Although phenobarbital has been used as a second-line agent in SE, phenytoin is preferred because by acting on voltage-gated sodium channels, its mechanism of action is different than lorazepam. Lorazepam and phenobarbital, on the other hand, are both GABA (γ-aminobutyric acid) receptor agonists. Phenobarbital and some newer anticonvulsant medications, such as levetiracetam, are considered third-line agents for SE. Consultation with a pediatric neurologist and/or pediatric intensivist are warranted when treatment beyond benzodiazepines is used.

Table 10-1 Suggested Treatment Algorithm for Status Epilepticus