Chapter 27 Neurologic Disorders

Anatomy and Physiology

Anatomy and Physiology

Anatomy

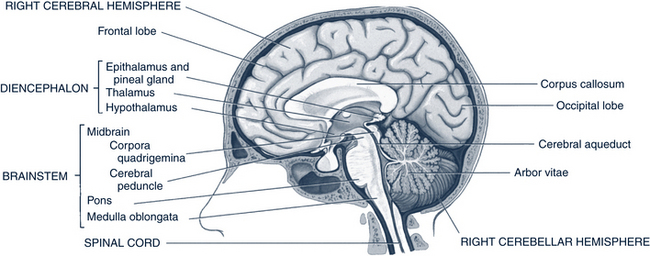

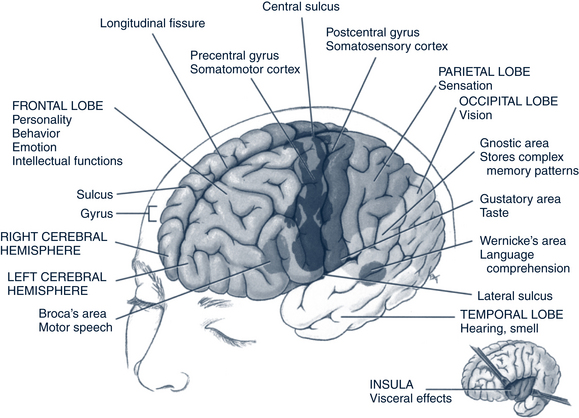

Briefly, the nervous system is divided into two parts: the CNS and the peripheral nervous system (PNS). The CNS consists of the brain and spinal cord. The PNS is made up of a network of afferent nerves and sense organs, which send information to the brain, and the efferent nerves, which send information out to the body for responses. Descending tracts from the brain to the gray matter of the spinal cord include the extrapyramidal tract, which conveys information from the cerebellum to the motor cells of the anterior column, and the pyramidal tract, which is the main motor pathway from the cerebral cortex to the spinal nerves and carries messages for voluntary movement. Most pyramidal tract fibers cross in the medulla, so the left half of the brain controls the right side of the body and vice versa. The anatomic units of the brain and their functions are listed in Table 27-1 and shown in Figures 27-1 and 27-2.

TABLE 27-1 Anatomic Units of the Nervous System and Functions

| Anatomic Unit | Functions |

|---|---|

| I. Central nervous system | |

| A. Brain | |

| 1. Forebrain—cerebrum | |

| a. Cortex (gray matter) | Posterior—motor skills |

| (1) Frontal area | Anterior—decision-making, emotions, memory, judgment, ethics, abstract thinking Broca’s area—speech |

| (2) Parietal area | Sensory integration, language, reading, writing, pattern recognition |

| (3) Temporal area | Memory storage, auditory processing, olfaction, limbic system in deep temporal lobe—arousal |

| (4) Occipital area | Visual processing |

| b. Diencephalon | |

| (1) Thalamus | Receives and sorts sensory input, modulates motor impulses from cortex |

| (2) Hypothalamus | Integrates autonomic functions |

| 2. Midbrain | Connects brain with cerebellum, pons, medulla |

| 3. Hindbrain | |

| a. Pons | Bridges cerebellum, medulla, midbrain; cranial nerves (CN) V, VI, VIII arise here |

| b. Medulla | Proximal end of spinal cord; contains reticular system—arousal; CN IX to XII arise here |

| c. Cerebellum | Coordination and movement; balance; smooth movements |

| B. Cranial nerves | Sensory and motor components; olfaction; vision; hearing; facial, tongue, pharyngeal, eye, shoulder movements |

| II. Spinal cord | |

| A. Dorsal roots | Afferent sensory fibers |

| B. Ventral roots | Efferent motor fibers |

| III. Protective layers | |

| A. Meninges | Protection of delicate nervous tissues |

| B. Ventricles | |

| C. Cerebrospinal fluid |

FIGURE 27-1 Lobes and functional areas of the cerebrum.

(From Polaski AL: Luckmann’s core principles and practice of medical-surgical nursing, Philadelphia, 1996, Saunders.)

Autonomic Nervous System

The visceral activities of the body (i.e., blood vessels, glandular secretions, gastrointestinal tract, cardiac muscle) are controlled by the autonomic nervous system (ANS). The ANS is comprised of the sympathetic system and the parasympathetic system, which are principally under the control of the hypothalamus. When the hypothalamus receives information from the cortical centers (e.g., visual, auditory, olfactory) and sensory stimuli from the various parts of the body (e.g., organs, glands), it functions as a “switchboard” between the two systems. Generally, both systems supply the same organs, glands, and smooth muscles. The sympathetic system begins in the thoracolumbar area of the spinal cord and extends distally; its function is often referred to as the “fight or flight” reaction. It is most active when an individual is physically or mentally stressed. The parasympathetic system begins in the medulla and midbrain with relays to the thalamus and higher centers. Enervation results in slowed activity, a decreased metabolic rate, and the conservation of energy; this system is active when an individual is mentally or physically relaxed. The principal sympathetic system neurotransmitters are epinephrine and norepinephrine. The parasympathetic fibers produce acetylcholine. The two systems function in balance—one excites and the other inhibits (Box 27-1). The enteric system is a component of the ANS, but does not play a role specifically in neurology. This system consists of a meshwork of nerve fibers that innervate the digestive system.

Pathophysiology and Defense Mechanisms

Pathophysiology and Defense Mechanisms

The nervous system is intimately related to functioning of the entire body; problems in any part of the system can have neurologic implications. Examples include uncontrolled firing of cerebral neurons (seizures); the inability of cerebral neurons to fire or the inability of the CNS to process stimuli and respond accordingly (coma); or the inability of peripheral nerves to respond to or receive signals through the pyramidal system of afferent and efferent nerves (paralysis). Other problems occur when special areas of the nervous system or individual nerves are damaged. Broad incapacity occurs with neurotransmitter problems. Many CNS disorders have interactive genetic, immunologic, and infectious factors that are probably causative (e.g., multiple sclerosis, cerebral palsy). Other causative factors include:

• Systemic Problems. The brain is extremely sensitive to changes in physiology anywhere in the body. Thus, any metabolic change, whether from external or internal factors (autoimmune, inflammatory, infectious causes), affects the CNS. Examples include delirium from toxins, diabetic coma, meningitis, epilepsy, ataxias, and chorea.

• Neurodegenerative Disorders. Neurodegenerative disorders result from a loss of structure or function of neurons in the brain or spine, including death of neurons. Many neurodegenerative diseases are caused by genetic mutations (e.g., multiple sclerosis, Rett syndrome).

• Genetic Problems. Many medical disorders have a genetic component that directly affects the nervous system. Some of the single-gene defects may have direct neurologic effects (such as neurofibromatosis), whereas others, typically inborn errors of metabolism, can have indirect effects via the abnormal metabolites released (e.g., phenylketonuria). Other examples of disorders with a genetic component include Tourette and Rett syndromes.

• Structural Defects. Because the CNS is structurally complex, there are many opportunities for defects to occur in utero. Examples of such defects include hydrocephaly, anencephaly, and spina bifida.

• Trauma. Head and spinal cord injuries are common and can have long-term, serious consequences for the child. Such complex neurologic tissue does not always heal in a way that results in full recovery of function(s).

• Tumors and Cancer. Benign or cancerous tumors evolve when there is a problem with cellular division. Problems with the body’s immune system can also lead to such tumors.

Assessment of the Nervous System

Assessment of the Nervous System

Assessment of the nervous system requires a careful history of the patient and family, and a detailed physical examination. The examiner needs to determine if a neurologic disorder exists and, if so, the disorder’s location and the patterns of impairment. For children with complex or severe neurologic problems, social, environmental, developmental, and family issues need thorough exploration. Historical information from patients more than 3 years old and from one or more family members provides the most accurate picture. Imaging or laboratory studies may be required.

History

Onset: When did the first symptoms appear? Was the onset insidious or sudden? Was it associated with an injury, insult, or recent exacerbating event? If yes, describe the event. Was the onset accompanied by any constitutional symptoms? How has the disorder evolved?

Onset: When did the first symptoms appear? Was the onset insidious or sudden? Was it associated with an injury, insult, or recent exacerbating event? If yes, describe the event. Was the onset accompanied by any constitutional symptoms? How has the disorder evolved? Pain and/or headache: Location and character, path of radiation, severity, extent of disability produced, effect of various activities or stimuli (including light sensitivity), relief measures, changes from day to night, effects of previous treatment, presence of pain or discomfort in other parts of the body

Pain and/or headache: Location and character, path of radiation, severity, extent of disability produced, effect of various activities or stimuli (including light sensitivity), relief measures, changes from day to night, effects of previous treatment, presence of pain or discomfort in other parts of the body Sensory deficits: Changes in hearing, vision, taste, loss of pain sensation, vertigo, dizziness, numbness, tingling

Sensory deficits: Changes in hearing, vision, taste, loss of pain sensation, vertigo, dizziness, numbness, tingling Injury: How, when (time and date), why, where, mechanism or manner in which the injury was produced: accidental or nonaccidental? Immediate treatment provided? If past injury, at what age did the injury occur?

Injury: How, when (time and date), why, where, mechanism or manner in which the injury was produced: accidental or nonaccidental? Immediate treatment provided? If past injury, at what age did the injury occur? Behavioral changes: Irritability, stupor, changes in appetite, lack of attention, random activity, emotional lability, changes in school performance

Behavioral changes: Irritability, stupor, changes in appetite, lack of attention, random activity, emotional lability, changes in school performance Prenatal history: Maternal and paternal ages, alcohol, drug ingestion (including environmental toxins, such as fish contaminated with mercury), radiation exposure, nutrition, prenatal care, injuries, hyperthermia, smoking, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or other infectious disease exposure, maternal illness, bleeding, toxemia, diabetes, previous abortions and stillbirths

Prenatal history: Maternal and paternal ages, alcohol, drug ingestion (including environmental toxins, such as fish contaminated with mercury), radiation exposure, nutrition, prenatal care, injuries, hyperthermia, smoking, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or other infectious disease exposure, maternal illness, bleeding, toxemia, diabetes, previous abortions and stillbirths Birth history and neonatal course: Place of birth, complications, labor and delivery, resuscitation, trauma, congenital anomalies, feeding history (reflux, colic, frequent formula changes), jaundice, convulsions, infection, gestational age, sleep disturbances, multiple birth. Low birthweight and failure to thrive have a strong effect on child development (Msall, 2009).

Birth history and neonatal course: Place of birth, complications, labor and delivery, resuscitation, trauma, congenital anomalies, feeding history (reflux, colic, frequent formula changes), jaundice, convulsions, infection, gestational age, sleep disturbances, multiple birth. Low birthweight and failure to thrive have a strong effect on child development (Msall, 2009). Injuries or infections: Meningitis, encephalitis, head injuries, seizures—types, frequency, medications; frequent musculoskeletal injuries (can suggest coordination or impulsive behavior).

Injuries or infections: Meningitis, encephalitis, head injuries, seizures—types, frequency, medications; frequent musculoskeletal injuries (can suggest coordination or impulsive behavior). Metabolic disorders: Diabetes mellitus, thyroid disease. Hypoglycemia causes confusion, convulsion, loss of consciousness. Hyperglycemia causes lethargy, coma. Hyperthyroidism causes tremor. Hypothyroidism causes weakness, coma.

Metabolic disorders: Diabetes mellitus, thyroid disease. Hypoglycemia causes confusion, convulsion, loss of consciousness. Hyperglycemia causes lethargy, coma. Hyperthyroidism causes tremor. Hypothyroidism causes weakness, coma. Review achievement of or loss of skills in all developmental milestone categories—language, gross motor, fine motor, social, and cognitive—and school performance. The Ages & Stages, Denver Developmental Screening Test II, and the World-class Instructional Design and Assessment (WIDA-ACCESS Placement Test [W-APT]) are useful.

Review achievement of or loss of skills in all developmental milestone categories—language, gross motor, fine motor, social, and cognitive—and school performance. The Ages & Stages, Denver Developmental Screening Test II, and the World-class Instructional Design and Assessment (WIDA-ACCESS Placement Test [W-APT]) are useful. Inquire about the effects of symptoms on all areas of health promotion and safety, nutrition, elimination, activity, communication, role relationships, values and beliefs, sexuality, sleep, coping (management style) and stress tolerance, temperament, and self-concept. The “management style” of family members is crucial to assess because it suggests how different family members may react over time to any chronic illness of their child (Shevell, 2009).

Inquire about the effects of symptoms on all areas of health promotion and safety, nutrition, elimination, activity, communication, role relationships, values and beliefs, sexuality, sleep, coping (management style) and stress tolerance, temperament, and self-concept. The “management style” of family members is crucial to assess because it suggests how different family members may react over time to any chronic illness of their child (Shevell, 2009). Inquire about the family composition (including critical family events such as additions or losses of family members); home, neighborhood, and school environment; culture and ethnicity; other stressors; strengths; resources; childcare; financial issues (socioeconomic status, poverty); identified social supports (e.g., family, friends, health professionals); and community agencies involved with the family and child.

Inquire about the family composition (including critical family events such as additions or losses of family members); home, neighborhood, and school environment; culture and ethnicity; other stressors; strengths; resources; childcare; financial issues (socioeconomic status, poverty); identified social supports (e.g., family, friends, health professionals); and community agencies involved with the family and child.

Physical Examination

The following should be noted:

• Growth pattern, including height, weight, body mass index (BMI), and head circumference

• Abnormalities of the skin (café au lait macules, angiomas, other pigmentation changes)

• Anomalies (for example, unusual facies, shape and number of digits, low-set ears)

• Cardiovascular system (including blood pressure)

• Musculoskeletal system: Gower’s sign, calf muscle hypertrophy, and muscular function

• Vision: eye problems, including cataract, corneal clouding, cherry-red spot, change of visual function

Specifics of the Neurologic Examination

Motor Examination

• Muscle strength and size. Look at muscle size, contour, and symmetry. Have the child stand from a lying position. Look for Gower’s sign (i.e., a child using the arms to push off from bent knees and gradually climbing the body and straightening up, which is common in children with muscular dystrophy). Ask the child to move extremities against resistance and to grip your fingers hard. The presence of muscular hypertrophy or hypotrophy should be noted.

• Muscle tone. Muscle tone might be considered the resting strength of the muscle. Is the trunk control and/or extremities floppy, rigid, or somewhat stiff when the child is resting or active? How difficult is it to move body parts passively? Tone may be increased or decreased all over or differ between the legs and the trunk and arms.

• Fine motor coordination. Fine motor coordination is tested by having the child pick up small pieces, write, stack blocks, copy pictures, turn book pages, put puzzles together, or do other hand activities.

• Involuntary movements. Tremors are fine involuntary movements. Chorea or choreiform movements are large, irregular jerking and writhing movements. Athetoid movements are slow writhing movements, especially of the hands and feet. Dystonia is an uncontrolled change in tone with movement and a tendency to hyperextend the joints.

• Reflexes. When a reflex is abnormal, the question is, why? Did the impulse not go through, or did the child have a problem in the ability to move responsively because of problems in efferent signals or muscle tissue contractility? (See section on reflexes that follows.)

• In an infant, assessing posture and muscle tone is fundamental. Motor testing should include observation for symmetry of movements, consistent fisting of the hands, opisthotonos, scissoring, abnormal tone, and tremors. The infant’s cry can be an indicator of several diseases (e.g., it is high pitched with increased intracranial pressure, resembles mewing in cri du chat syndrome, and is hoarse with hypothyroidism).

Reflexes

• Deep tendon reflexes include the biceps, brachioradialis, triceps, patellar, and Achilles.

• Superficial reflexes include the upper abdominal, lower abdominal, cremasteric, gluteal, and plantar.

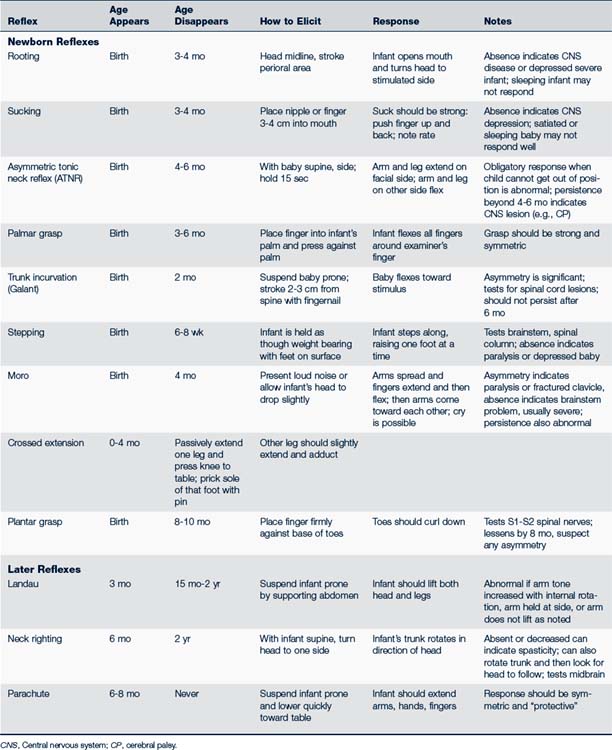

• Primitive reflexes include sucking, rooting, asymmetric tonic neck, grasp, trunk incurvation, stepping, and others found in Table 27-2. These primitive reflexes can be absent or decreased in a satiated or sleepy infant. Tendon reflexes can be tested in an older child. In older children and adults, a Babinski sign is an important sign of upper motor neuron disease.

Autonomic Nervous System

Alterations in blood pressure, sweating, or body temperature can be indicators of ANS problems.

Diagnostic Studies

• Radiographs have relatively little diagnostic value for the neurologic system since the advent of computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). CT scans display differences in density of the intracranial tissues and structures. MRI provides additional information related to aneurysms (e.g., hemorrhages, calcifications, abscesses), brain structure, and the cellular activity of various parts of the neurologic system (e.g., tumors, CNS, spinal cord, and malformations). There may be a medical need to order more specific tests, such as a magnetic resonance angiogram (used to detect blood vessel stenosis and aneurysms) or functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI—used to detect subtle metabolic changes in the brain that indicate how certain parts of the brain are working). A neurologic consultant can advise when these would be necessary.

• Laboratory studies provide indicators of systemic disease, infection, or inflammation. They are especially important for children receiving medication for seizures. Drug levels, liver function, and blood studies may need to be monitored routinely.

• Lumbar puncture provides information about metabolism, infections, and trauma.

• The electroencephalogram (EEG) provides information about the electrical activity of the CNS, which is important in assessing function rather than structure.

• Ultrasonography can be useful in infants to evaluate brain tissue.

• Other studies can include polysomnography (helps assess narcolepsy, apnea of infancy, certain movement disorders, and nocturnal seizures); electromyography (tests muscle activity); nerve conduction studies; evoked responses (brainstem—auditory, somatosensory, and visual); electronystagmography (measures eye movements to assess vertigo and postconcussion syndrome); and cerebral arteriography (visualizes cerebral blood vessels to evaluate vascular anomalies and tumors).

Management Strategies

Management Strategies

Counseling

• Impairment: Existence of a deviation from normal activity or an inability to control an involuntary movement (one can be impaired without being disabled)

• Disability: A restriction in an ability to execute a normal activity of daily living that someone of similar age could execute (all people with disabilities are impaired)

• Handicap: Existence of a disability that prevents the person from achieving a normal role in society that someone of a similar age is expected to achieve (all people with handicaps have disabilities)

• “Extra needs” versus “special needs” is a more socially acceptable and easily understood term to use when referring to a person.

Physical, Occupational, and Speech Therapy

Physical therapy (PT) can be useful to help restore or maintain function or to teach new motor skills. The physical therapist should be accustomed to dealing with children. PT services are often combined with occupational and speech therapy to promote maximal development. Early intervention programs offer such assistance in many states and are generally free to qualifying patients. Should any services be denied, families should be advised to inquire about the appeal process in their state. Federal funding is available in most states for therapy programs for children from birth through 2 years of age.

Specific Neurologic Problems of Children

Degenerative Disorders

Degenerative Disorders

Multiple Sclerosis

Description and Epidemiology

MS occurs in 5% of children before the age of 16 (Banwell, 2009). It is exceptional to have symptoms occur before a child is 10 years old (0.2% to 2% of all cases). Two to three times as many females as males are affected. It is widely believed that MS is an autoimmune inflammatory neurodegenerative disorder of the CNS. Macrophages, activated T-lymphocytes, and other destructive molecules are stimulated by yet not fully understood events. These inflammatory cells cause both CNS demyelination and axon damage within the white brain matter, including the optic nerve. Research is focused on environmental (including geography and living north of 40 degrees latitude), infectious, toxic, immunologic, hormonal, or genetic causes. No specific virus has been isolated, although the most promising agent seems to be the Epstein-Barr virus. Some scientists propose that it is multifactorial (National MS Society, 2010).

Clinical Findings

Symptoms are the same for children as for all other ages. These include (Banwell, 2009):

• Unilateral weakness or ataxia (frequent presenting symptom).

• Symptoms that last more than 24 hours.

• Headache (may be severe, prolonged, generalized).

• Vague paresthesias of lower extremities, distal portions of hands and feet, and face.

• Visual disturbance (diplopia, blurred vision, or sudden loss of vision as a result of optic neuritis).

• Concurrent optic neuritis and transverse myelitis (referred to as neuromyelitis optica or Devic disease).

• Vertigo, dysarthria, and sphincter disturbances are uncommon. Neurogenic bladder may present in acute transverse myelitis.

• Repeated episodes are frequently preceded by fever, nausea and vomiting, and lethargy may occur within months or years of each other.

Diagnostic Studies

• Neuroimaging. An MRI (gadolinium enhanced) early in the course of the disease can be important in predicting the clinical future. In children demyelination of white matter presents as well defined and perpendicular to the corpus callosum. Evidence of disturbance of the blood-brain barrier is thought to be a better predictor than the number of T2 white matter lesions for developing inflammatory MS lesions and atrophy. Gray matter lesions are believed to play a role but are undetectable using current imaging.

• Later in the course of the disease, nonconventional neuroimaging techniques (magnetization transfer imaging and imaging for whole brain atrophy) are more useful than the gadolinium-enhanced MRI for tracking the progression of disability.

• Other studies may include a lumbar puncture (may show oligoclonal bands) and visual-evoked responses.

Nondegenerative Disorders

Nondegenerative Disorders

Benign Paroxysmal Vertigo

• Acute unsteadiness; the child may fall or refuse to walk or sit; may grab on to a parent or object for steadiness.

• Nystagmus may be present; no loss of consciousness with events.

• Vomiting and nausea may be present and be quite prominent.

• Appearance of child is frightened and/or pale.

• Child may be lethargic or drowsy; some children may sleep and return to normal activities on awakening (Martin Sanz and Barona de Guzman, 2007).

• Neurologic examination is essentially negative except for abnormal vestibular function.

Cerebral Palsy

Description

There are three major types of CP: spastic, athetoid (or dyskinetic), and ataxic. Spastic is when the muscles stiffen, causing muscle tightness. Athetoid affects the muscles that enable smooth, coordinated movement and maintain body posture; without this control movement becomes involuntary and purposeless. The ataxic type affects balance and coordination. Children may exhibit varying degrees of involvement and severity; capabilities may improve over time depending on the degree of involvement and treatment. Table 27-3 lists more terms that describe CP.

TABLE 27-3 Terms Used to Describe Cerebral Palsy

| Movement Type | Description | Associated Impairments |

|---|---|---|

| Spastic | Inability of a muscle to relax | Often evident after 4-6 months; retarded speech; convergent strabismus; toe-walking; flexed elbows; delayed walking until 18-24 months; one third have seizures |

| Athetoid | Inability to control muscle movement (continuous, writhing movements) | Infant has difficult feeding as a result of tongue thrust, is initially hypotonic with head lag; increasing tone with rigidity over time; speech delay |

| Ataxic | Problems with balance and coordination | Tremors |

| Body Part Involved | ||

| Diplegic | Affects both legs more than both arms | Most have limited use of legs; can walk often with aids; walk typically “scissor-like” with knees bent in and crisscross over each other |

| Hemiplegic | Affects one side of the body (upper extremity is usually affected more than the lower extremity) | Often not detected at birth; right side often more affected than left; 50% develop seizures; growth arrest of affected limb(s); individuals usually able to walk |

| Tetraplegic/Quadriplegic | Affects all four extremities, trunk and head | Affects upper extremities more than lower; 50% with grand mal seizures; IQ impairment can be severe; most unable to walk or stand |

| Specific Problems With Movement or Function | ||

| Dystonia | Involuntary, slow, sustained muscle contraction | Abnormal posture, writhing motion of arms, legs, trunk |

| Choreic | Disorganized tone | Uncontrollable jerky movements of toes and fingers |

| Tremor | Involuntary, rhythmic movements of opposing muscles; can affect extremities, head, face, vocal cords, trunk | |

| Ballismus | Violent, jerky movements; may affect only one side of body | |

| Rigidity | Stiffness | |

Epidemiology

CP was once believed to be caused only by birth complications (neonatal or perinatal asphyxia or trauma), but the Collaborative Perinatal Project demonstrated that most children with CP were born at term without complicated labors and deliveries (Johnston, 2007). The etiology is unknown in a large percentage of cases. Small-for-gestational-age, low birth-weight (less than 1000 g), or preterm babies (less than 37 weeks of gestation), and multiple births are at greater risk for CP. Complicated labor and delivery, breech presentation, Apgar score of less than 3 at 10 minutes or more; traumatic delivery; microcephaly; exposure to maternal infection (evidenced by chorioamnionitis, inflamed placental membranes, umbilical cord inflammation, foul-smelling amniotic fluid, maternal temperature greater than 100.4° F [38° C] during labor, or urinary tract infection [UTI]); maternal vaginal bleeding (between the sixth and ninth month of pregnancy); severe proteinuria late in pregnancy; maternal hyperthyroidism, mental retardation, and seizures; intracranial hemorrhage; toxemia; preeclampsia; antepartal hemorrhage; postmaturity; fetal distress; maternal stroke; coagulation in the fetus or newborn; and neonatal seizures are considered risk factors (Menkes and Moser, 2006). Other etiologies may include intrauterine drug exposure (e.g., alcohol, cocaine, tobacco, crack cocaine), intrauterine infections (e.g., cytomegalovirus, toxoplasmosis, rubella), and congenital brain malformations. In the U.S. it is estimated that children who acquire CP postnatally account for 10% to 20% of those with the disorder. In such cases, the cause can be attributed to meningitis, encephalitis, head trauma (e.g., secondary to shaken baby syndrome or other abuse, car accidents, falls), and kernicterus (Brunstrom and Tilton, 2009).

Clinical Findings

History

The history should include pathologic, developmental, and functional health patterns.

Pathology

• Prenatal/natal history of risk factors as listed previously

• Hearing and vision or ocular problems, such as strabismus, nystagmus, optic atrophy

• Change in growth parameters, especially decreased head circumference

• Early head injury or meningitis

• Muscle tone (can be hypotonic before 6 months old then become hypertonic, as evidenced by unusual posture or favoring one side). Preterm infants with generalized, prolonged, and cramped synchronized movements are more often diagnosed with CP at a later time (Brunstrom and Tilton, 2009).

Functional Health Patterns

• Feeding history of regurgitating through the nose, inability to coordinate suck and swallow, inability to advance the diet to textured foods—in short, oral-motor coordination problems

• Irritability or depressed affect (including unusual sleepiness) as a neonate

• Difficulty with movement, cuddliness, grasp and release, self-feeding, and head control to look around; inability to change position per developmental level

• Persistent primitive reflexes

• Communication problems, either in language or speech proficiency

Physical Examination

• Skin: Dermatologic signs of syndromes, such as neurofibromatosis, may be present.

• Orthopedic examination: Scoliosis, contractures, and dislocated hip may be present.

• Neurologic examination: The following may be seen:

Tone increased, although occasionally decreased; hypotonia before 6 months old is common. Tone may also be mixed.

Tone increased, although occasionally decreased; hypotonia before 6 months old is common. Tone may also be mixed. Delayed reflexes (e.g., parachute reflex remains absent after 9 to 10 months old; side-protective reflexes remain absent after 5 months old)

Delayed reflexes (e.g., parachute reflex remains absent after 9 to 10 months old; side-protective reflexes remain absent after 5 months old)• Vision and hearing: Visual refractive errors occur in 50% of children; strabismus is found in 33%. Hearing problems may have resulted from the initial brain insult.

• Development: Assess gross motor, fine motor, language, and personal social skills. The Denver Developmental Screening Test II (Denver II) can be used for initial screening. Motor milestones are commonly delayed. Note quality of movements (e.g., smoothness of gait, grasping, clarity of speech).

• Feeding: Note a reversed swallow wave; uncoordinated suck and swallow; decreased tone of the lips, tongue, and cheeks; increased gag reflex; involuntary tongue and lip movements; increased sensitivity to food stimuli; poor occlusion; and delayed inhibition of the suck reflex.

• Evaluate the diet, height, weight, and BMI for adequate nutrition.

Diagnostic Studies

• Imaging studies. A CT scan can be obtained to identify brain malformations. An MRI will aid the visualization of structures and abnormalities that are nearer to bony structures.

• Chromosomal and metabolic studies. These studies can be done to identify genetic disorders, especially single-gene defects.

Differential Diagnosis

The first and main requirement is to differentiate central from peripheral disorders. CP is always central and is characterized by brisk deep tendon reflexes. Many other conditions can have CP motor involvement features. These conditions include sepsis from intrauterine infections, fetal alcohol syndrome, hydrocephalus, tumors, agenesis of the corpus callosum or other brain malformations, Tay-Sachs disease, phenylketonuria, Lesch-Nyhan syndrome, spinal cord injury, hypothyroidism, muscle diseases, seizures, and many genetic and metabolic disorders (e.g., cerebral folate deficiency) (Djukic, 2007; Steinfeld et al, 2009 ). Mental retardation results in delayed milestones but should not result in increased reflexes. Neuromuscular disorders are associated with signs of weakness, muscle atrophy, and decreased deep tendon reflexes. These disorders typically present with a missed milestone.

Management

• Referral of suspected cases. Children with CP should be evaluated and cared for at centers that provide interdisciplinary caregivers, including a developmental pediatrician, gastroenterologist, orthopedist, neurologist, nurse, speech pathologist, physical and occupational therapists, education consultant and psychologist, and social worker. Care may also involve an ophthalmologist, feeding clinic and nutritionist services, and genetics counseling.

• Family education about the diagnosis. Families need to understand the diagnosis and its nonprogressive but incurable characteristics. They need to understand that the extent of brain damage is not always related to the extent of disability; no one can predict what the future for a given child will be. Children who receive special services—physical therapy, speech therapy, and other interventions—have better outcomes than children who are left to develop on their own. United Cerebral Palsy has educational materials and a variety of services available.

• Family support. Generally, families grieve when given the diagnosis of CP and need support during this time. Support groups or opportunities to meet other families with affected children are often helpful. The emotional needs of siblings must not be overlooked. The social worker can be very helpful to families trying to cope with complex health problems.

• Financial resources. CP services are long term and expensive. Many children will be eligible for Supplemental Security Income or state program benefits for the severely handicapped. Respite care may be available. The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act of 1997 (IDEA) requires children with disabilities to be assessed for and instructed in the use of assistive devices along with appropriate referrals to regional centers. Some insurance companies try to avoid the costs of long-term care and therapy. Medical social workers and public health nurses can be very helpful in connecting families to appropriate services.

• Nutrition. Children with CP often have inadequate nutrition because of their problems with biting, sucking, chewing, swallowing, and self-feeding. Additionally, children with athetosis may need as much as 50% to 100% more calories to support their increased caloric needs because of their constant writhing movements. Children with spasticity, on the other hand, may need fewer calories because of their decreased movements. Occasionally, the problems are so severe that a gastrostomy is needed, sometimes with fundoplication to prevent reflux and aspiration. Special positioning, feeding therapy, and special feeding devices can help. High nutrient density is a key to providing a nutritious diet (i.e., getting more nutrients into the same volume of food) (also see Chapter 10). Feeding clinics are often helpful.

• Elimination. Constipation is common because of lack of exercise, inadequate fluid and fiber intake, medications, poor positioning, low abdominal muscle tone, and other factors. Stool softeners, such as docusate sodium, may help. Laxatives, such as senna concentrate or Milk of Magnesia, may be useful but should not be used long term. Osmotic agents may also be used (e.g., polyethylene glycol). Bladder control and urinary retention are also problems in CP; these children are three times more likely to suffer UTIs (Richardson and Palmer, 2009).

• Most children achieve bladder control between 3 and 10 years old. For some, toilet training may be difficult, especially for those with mental retardation.

• Dentistry. Orofacial muscle tone can contribute to malocclusion. Problems with oral mobility make daily dental hygiene difficult, leading to more gum disease. The side effects of some seizure medications can include swollen gums and tooth decay. A careful dental care program is necessary (see Chapter 33: Dental Care of Children with Extra Needs).

• Drooling. Inability to manage oral secretions results in drooling. Social isolation, wet clothing, skin excoriation, malodorous breath, discomfort, choking, gagging, and aspiration can make these oral secretions a serious problem. The anticholinergic, glycopyrrolate, is approved for use in those 3 to 16 years old with chronic excessive drooling from neurologic conditions. This cherry-flavored oral solution (1 mg/5 mL) is dosed at 0.05 to 1 mg by mouth two or three times daily. Side effects may be problematic (e.g., dry mouth, vomiting, constipation, flushing, urinary retention, and nasal congestion). Clinical improvement in drooling has been demonstrated in up to 78% of children and adolescents who used this drug (Waknine, 2010). Surgical intervention is a last resort and commonly involves removing the submandibular gland or nerves, or cutting or rerouting the salivary duct.

• Respiratory. Positioning problems, an increase in gastroesophageal reflux disorder, and difficulty in clearing secretions place children with CP at higher risk for respiratory problems, notably pneumonias (especially from aspiration). The duration of respiratory symptoms with upper respiratory infections (URIs) is increased in these children because they may have congenital paralysis or sleep-related obstruction (Daniel, 2006; Hill et al, 2009). A tracheotomy may be necessary in severe cases of upper airway obstruction or difficulty.

• Skin. The skin in sedentary children is more likely to break down and cause decubitus. There is an increased incidence of skin latex allergies with CP (Behrman and Adler, 2008).

• Movement and mobility. Positioning and seating, standing, transportation, bathing, dressing, mobility for play and getting to school are important to assess and manage. Occupational and physical therapists are essential to these aspects of care, and families need their help incorporating various strategies into their homes and lifestyles. The goals of therapy are to improve physical conditioning and gain maximal independence in mobility, fine motor activities, self-care, and communication by promoting efficient movement patterns, inhibiting primitive reflexes, and achieving isolated extremity movements. Bracing, postural support and seating systems, adaptive devices, and early intervention programs beginning in infancy are important. Open-front walkers, quadrupedal canes, gait poles, wheelchairs, and motorized wheelchairs are beneficial in helping children explore their environment more efficiently. Although the condition is not progressive in terms of the brain lesion, contractures, scoliosis, dislocated hips, and other deformities can develop if the child is allowed to maintain abnormal positions for long periods; range-of-motion exercises are a long-term need. Orthopedic care may be necessary. Constraint-induced therapy (the use of the more functional side is restricted) can both improve mobility function and sustain function longer than conventional physical therapy in children with CP (Taub et al, 2004).

• Medications. Antispasmodic medications (baclofen, tizanidine, diazepam, and dantrolene) may be used to minimize contractures and spasticity. They are appropriate for children needing only a mild decrease in their muscle tone or in those with widespread spasticity. For results, dosages often need to be high, and side effects can result (drowsiness, upset stomach, high blood pressure, and possible liver damage with chronic use).

• Botulinum toxin A injections are used to eliminate pain, minimize contractures, delay or prevent surgery, and maximize function (Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the Practice Committee of the Child Neurology Society et al, 2010). Although botulinum toxin A has become standard treatment in pediatrics, it is used off-label (NINDS, 2010b). Its use is dependent on the recommendation of—and after a thorough evaluation by—a pediatric physiatrist, pediatric neurologist, or pediatric orthopedic surgeon, and after input of therapists and family. It is injected directly into muscles (sometimes guided by an electromyogram or electrical stimulation). The child may experience mild flulike symptoms and transient worsening of spasticity; for this reason, injections are best followed by physical and occupational therapies that help strengthen the antagonist and agonist muscles (NINDS, 2010b). The dosage administered depends on which muscles are being selected and muscle size. Results are generally seen within 5 to 7 days and last 3 to 4 months. The toxin has been safely used in infants older than 1 month. Resistance can occur because neutralizing antibodies can develop. Therefore, only the smallest possible effective dose must be used, and at least 3 months must lapse between injections. Contraindications include diffuse hypertonia, myasthenia gravis (MG), motor neuron disease, injection into an infected muscle, caution in pregnancy (fetal complications have been seen in animal studies), and caution when it is coadministered with an aminoglycoside or another agent that interferes with neuromuscular transmission (toxin effect can be increased) (Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the Practice Committee of the Child Neurology Society et al, 2010). The numerous side effects should be thoroughly understood by care providers.

• Communication. With the combined problems of lack of oral-motor control and the high incidence of mental retardation, communication can be a problem. Speech therapy may be of assistance; augmentative devices, such as computers with voices, can allow for language development and communication of needs even without oral speech. Hearing deficits need to be identified and managed by an audiologist.

• Vision. Visual acuity, eye tracking, and binocularity are key factors to be assessed by a pediatric ophthalmologist (Brunstrom and Tilton, 2009).

• Osteopenia. Individuals with CP are at risk of bone density loss secondary to their inability to ambulate and place weight on their bones. Some medical providers prescribe bisphosphonates off-label to children (NINDS, 2010b).

• Pain. Spastic muscles, strain on compensatory muscles, and frequent or irregularly occurring muscle spasms can cause chronic and acute pain. Diazepam, gabapentin, and complementary therapies (distraction, biofeedback, relaxation, therapeutic massage) can help (NINDS, 2010b).

• Special Education. Early intervention programs and specialized educational programs through school systems are often beneficial.

• Other Treatments. Surgery is used to release contractures or to sever overactivated nerves (called a selective dorsal root rhizotomy). Selective dorsal root rhizotomy (of spinal nerves) plus intrathecal baclofen decrease spasticity and increase range of motion of affected limbs. Intrathecal baclofen uses an implantable pump to deliver the drug, a muscle relaxant. The pump is programmable with an electronic telemetry wand. Pumps have been successfully implanted in children as young as 3 years of age; this treatment has small but significant risks of complications. It is most efficacious in children who have some motor movement control and who have few muscles to treat that are not fixed or rigid (NINDS, 2010b). Intense physical therapy is an instrumental adjunct treatment.

• Strength training can help with balance and weakness. Functional electrical stimulation (involves insertion of a microscopic wireless device into specific muscles or nerves) has been used to activate and strengthen muscles in the hand, shoulder, and ankle. It should be regarded as experimental in CP and is used only as an alternative treatment if other treatments fail to relax muscles or relieve pain (NINDS, 2010b).

• Alcohol “washes” (injections of alcohol into targeted nerves) are sometimes used. Benefits can last from months to 2 years or more; side effects include significant risk of pain or numbness. Research is moving in the direction of developing chemodenervation techniques that deliver injected antispasmodic medications more precisely to target and relax muscles (NINDS, 2010b).

• “Patterning” is a controversial physical therapy (child is taught elementary movements, such as crawling, before advancing to walking skills). The American Academy of Pediatrics and other organizations do not endorse this technique because of the lack of evidence-based studies. Likewise, the Bobath technique (involves inhibiting abnormal movement patterns in favor of more normal ones) has provoked strong reservations about efficacy. Conduction education (use of rhythmic activities combined with physical maneuvers on special equipment) has failed to consistently produce improvement (NINDS, 2010b).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree