39 Neurologic Diseases

It truly takes a village to meet the complex needs faced by children with neurologic conditions and their families. Front and center to this village are the parents and day-to-day care providers of such children, the ones who see the nuances of how a specific disease or condition manifests in an individual child. Medical teams bring expertise in the spectrum of problems seen in many children with similar conditions; parents often bring expertise in how these problems look in their child. Along with the medical needs of such children, families face myriad challenges that exist in the context of their hopes, fears, beliefs, values, the uncertainty of a their child’s condition, and the community where they live. Table 39-1 is an introduction to the expertise available from palliative care and hospice teams to assist with the needs of such children and their families.

TABLE 39-1 Team Member Expertise

| These individual areas of expertise are critical to managing the multidimensional needs encountered. Though an individual of an interdisciplinary team will bring in expertise in one of these areas of need, each member will bring skills in assisting with all areas. |

| Social workers |

| Provide emotional support to family, psychosocial assessment and supportive counseling in collaboration with other providers for families adjusting to palliative care issues, link to psychosocial and mental health resources in the local community, anticipate legal and financial needs including guardianship, government programs that cover some medical expenses, and special needs trust, and direct to appropriate resources |

| Child life specialists |

| Assist siblings with the fears of having a sister or brother with complex healthcare needs, assist families with memory making and legacy of the child, provide bereavement support, provide education around appropriate grief responses of children |

| Chaplains |

| Support faith traditions and spiritual values that promote healing and hope, support families as they face loss and grief, identify religious and cultural factors that can shape how a family faces illness and suffering, provide a supportive presence for sick children and their families, provide support and advice in learning how to respond to the suffering witnessed by medical care teams |

| Nurses |

| Assist with bedside assessment of pain and other distressing symptoms, work with families and other care providers to determine what specific features in a nonverbal child with NI indicate specific distressing symptoms such as pain and dyspnea, translate this information into a care plan that is translatable to other care providers, listen in real time during times of emotional and spiritual distress for families |

| Physicians and advance practice nurses |

| Expertise in symptom management, serve as mediators between the medical teams and families, assist with advanced directives by working with medical teams and families, assist with translating goals of care to how medical interventions can or cannot meet those goals, review autopsy, tissue and organ donation, and Brain and Tissue Bank with families |

Pediatric Palliative Care and Neurologic Conditions

Pediatric palliative care teams are commonly consulted to see children who have diseases and impairments of the nervous system. Of children enrolled in a pediatric palliative care project, 44% were categorized with a primary neurologic condition (24% of those were deemed progressive neurologic, 20% were CNS damage) and 15% frequently have associated neurologic impairment (10% with congenital anomalies and 5% with metabolic).1 Recent data for the Pediatric Advanced Care Team (PACT) at Children’s Hospital Boston and Dana Farber Cancer Institute categorized 37% neurologic and 10% genetic or metabolic.2 Unfortunately, little has been written about palliative care as it pertains to children with neurologic impairment (NI) and their families.

The personal challenges experienced by children and their families exist within the larger context of societal debates regarding medical decision making for such children. These discussions are guided and influenced by ethics, morality, religion, personal values, justice, resource usage, and quality of life. Case reports in the literature highlight the variability of this debate with examples of doing everything, possibly so as to not create the impression of discrimination based on disability3 and not offering treatment out of an assumption of poor quality of life.4 As society wrestles with these challenges, we must avoid bringing this debate to the bedside and instead be guided by legal and ethical knowledge while providing compassion and support.

Patient Population

There are a broad range of conditions with NI that benefit from pediatric palliative care.5 The conditions may be:

Conditions and suggested timing of palliative care consultation are summarized in Table 39-2; assistance with symptom management can occur at any point in time.

TABLE 39-2 Neurologic Conditions and Timing of Palliative Care Consults

| Category | Conditions | Timing of consultation |

|---|---|---|

| Severe disability causing vulnerability to health complications and/or palliative after diagnosis | Recurrent illness, hospitalizations, symptoms, or decline in health and function, such as respiratory exacerbations, feeding intolerance, recurrent or chronic irritability and/or pain | |

| Intensive long-term treatment aimed at maintaining the child’s quality of life | Consideration of gastrostomy feeding tube placement. This is an opportunity to identify goals of care that will then be relevant to future decision making such as use of mechanical ventilation | |

| Curative treatment intended but may fail |

Unique experiences and challenges

Loss is a recurrent theme, starting from the time of diagnosis. This theme is often repeated when what the child cannot do and the ongoing problems that cannot be fixed are reviewed at medical appointments. This journey often includes chronic sorrow, a phrase used to describe sorrow over time in response to ongoing loss.6 Examples may include loss of functional ability, loss of ability to meet nutritional and fluid needs through eating, and loss of health. Families are also simultaneously exploring meaning and hope in the context of their values, beliefs, relationships, and supportive networks. They may find joy in little victories, outcomes that were not expected, as they navigate hope, meaning, loss, and uncertainty.

What to Expect: Life Expectancy Literature

Information about life expectancy demonstrates a wide variation. The more severe the motor disability, such as the inability to lift the head up when prone, the more likely the child will not survive to adulthood.7–12 Survival for individuals with CP that includes severe impairment in cognitive function, motor ability, vision and hearing was 50% at 13 years and 25% at 30 years.9 It is beneficial to understand that CP is not a diagnosis but a developmental label indicating impairment of motor control as a result of non-progressive impairment of the central nervous system acquired at an early age. Information and experience from CP is relevant to any disease that results in severe motor impairment.

Framework for Approaching Prognosis, Uncertainty, and Decision Making

Literature and experience demonstrates a wide range in life expectancy, yet has provided limited information on how families approach this uncertainty. Studies13,14 of the experience of families with children dying from neurodegenerative conditions identify how they navigate uncharted territory and use strategies such as seeking and sharing information, focusing on the child, reframing the experience, and promoting the child’s health. Factors influencing parental decisions to limit or discontinue medical interventions include perception of their child’s suffering, likelihood of improvement, perception of their child’s will to survive, quality of life, previous experience with end-of-life decision making for others, and financial resources.15,16

Illness trajectory as a guide to decision making

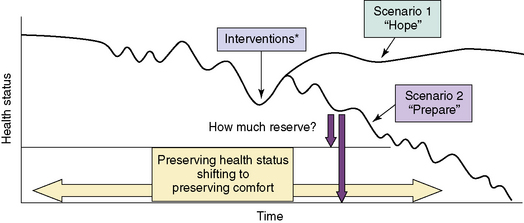

Adult literature describes illness trajectories for cancer, organ failure, and frailty.17,18 Using the latter two trajectories and experience, Fig. 39-1 provides a hypothetical framework for reflecting on and anticipating the trajectory of a child with NI. The figure is intended to guide families through decision making by using a reflection on the past benefit of interventions to anticipating the probable and possible future benefit by hoping for the best, preparing for the worst.19

The hypothetical disease trajectory highlights that many health issues in children with NI progress gradually with initial benefit and return to health and functional baseline with treatment available. Over time, less return to baseline will occur from the interventions available, reflecting the inability to fix the problems that are secondary to the permanent NI. Predicting outcome at the beginning of the trajectory before any decline in health status is seen can result in pressure of past success20 when the outcome is better than predicted. Asking a parent of a child with NI to make a decision to limit interventions before the child has had any significant decline in health may feel as if the emphasis is on limiting interventions because of the disability. By identifying associated health problems, monitoring for changes in health status, and noting any decreased benefit from treatments, we can identify individuals with NI who are at risk for life-threatening events.

Reflective questions with parents and care providers:

Advance care planning: how to hope and prepare

Areas of need as a result of slow decline include planning for future problems, avoiding interventions of limited benefit, and assistance for long-term caregivers.21 A goal is to facilitate planning by giving physicians permission to discuss what-if scenarios while giving parents permission to maintain hope. Palliative care can assist with this process by exploring psychosocial, spiritual, and physical needs that impact on decisions, such as the worry of giving up, a sense of needing to do something, and the fear that treating physical suffering will result in an early death. Given the inherent challenge of determining when goals shift from preserving health status to preserving comfort, medical, and palliative care are ideally integrated together for children with NI.22,23 Through this process of exploration with families and by integrating symptom-directed treatment into medical care plans, we can minimize the impression of choosing treatment that preserves life vs. comfort care that means giving up.

Several details about resuscitation are important for children with NI:

This is also a time to review that a decline in health is not a result of the care provided at home or a result of decisions made. Rather, it reflects the health problems that cannot be cured or fixed, while providing reassurance that interventions will be used for as long as the parents identify them as meeting goals. Several articles provide further beneficial communication strategies.24,25

Documenting, Communicating, and Coordinating Plans of Care

Symptom Management

Children with NI experience pain more frequently than the general pediatric population.26–29 Caregivers of children with severe cognitive impairment reported 44% experiencing pain each week over a 4-week interval. Pain frequency was higher in the most impaired group of children.27 In a study of nonverbal cognitively impaired children, caregivers reported that 62% experienced five or more separate days of pain and 24% experienced pain almost daily.29 In addition, children with severe-to-profound cognitive impairment were found to have elevated pain scores at baseline on two pain assessment scales.30

Other distressing symptoms commonly encountered in children with NI include: 31–33

In addition, depression and anxiety may be experienced at an increased rate by children with a muscular dystrophy (MD) such as Duchenne MD.34 Unfortunately, few studies have explored symptom management in children with NI both during life and at the end of life.

General approach

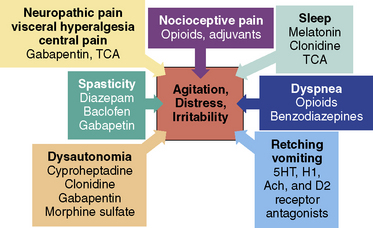

This section will outline management of distressing symptoms for children with NI (Fig. 39-2). This allows the healthcare provider to consider interventions that may benefit several problems. This can be helpful because it is not always possible to determine which symptoms or problems are the primary source of distress and which ones are the secondary manifestations in these children. Is the nonverbal neurologically impaired child irritable and in distress because of spasticity or is the spasticity secondary to underlying pain? Are the signs and symptoms of dysautonomia caused by pain, mimic the appearance of pain, or do the associated problems of dysautonomia contribute to pain? Given these challenges, it is helpful to focus on all potential sources of distressing symptoms, including neuropathy. The focus of this section will be on nonverbal children with NI given the inherent challenge with this group.

Fig. 39-2 Multidimensional symptom assessment and management.

(These symptoms are sources of agitation, distress, and irritability in neurologically impaired children.)

Assessment

The options for assessing presence and severity of pain include self-report, observational assessment of behaviors in nonverbal children, and assessment of physiological markers. Knowledge of the child’s cognitive level allows selection of a validated pain rating tool appropriate for the level of intellectual function such as The Poker Chip tool, the Oucher,35 and the Wong-Baker FACES pain rating scale36 for children at a cognitive level of 5 to 6 years.

Assessment Tools

Observational pain assessment tools assist with identifying the presence of pain and monitoring improvement in pain when an intervention is introduced. (Box 39-1).37–49 In a comparison of the revised-Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability (r-FLACC) tool, the Non-Communicating Children’s Pain Checklist-Postoperative Version (NCCPC-PV), and the Nursing Assessment of Pain Intensity (NAPI), the r-FLACC and NAPI were identified as having a higher overall clinical utility based on complexity, compatibility, and relative advantage.37 The r-FLACC was the tool most preferred by clinicians in terms of pragmatic qualities.

BOX 39-1 Pain Assessment Tools for Non-Verbal Neurologically Impaired Children

The Non-Communicating Children’s Pain Checklist-Revised (NCCPC-R)40,41

30-item standardized pain assessment tool for children with severe cognitive impairment.

Paediatric Pain Profile (PPP)42,43

Sensitivity (1.0) and specificity (0.91) optimized at a cut-off of 14/60

Available to download from the web following registration at www.ppprofile.org.uk.

Evaluation

This section discusses the sources of pain in neurologically impaired children.

Nocioceptive: Tissue Injury and Inflammation

Commonly recognized pain sources in children with NI include acute sources, such as fracture, urinary tract infection, or pancreatitis;51 and chronic sources, such as gastroesophageal reflex (GER), constipation, feeding difficulties from delayed gut motility, positioning, spasticity, hip pain, or dental pain. (Box 39-2).

BOX 39-2 Etiology of Pain/Irritability in Nonverbal Neurologically Impaired Children

Abdomen

Liver and/or gallbladder: hepatitis, cholecystitis

Renal: urinary tract infection, nephrolithiasis, neuropathic bladder, obstructive uropathy

Genitourinary: inguinal hernia, testicular torsion, ovarian torsion and/or cyst, menstrual cramps

Neuropathic: Peripheral Neuropathy and Central Pain

Neuropathic pain conditions are those associated with injury, dysfunction, or altered excitability of portions of the peripheral, central, or autonomic nervous system. It can be caused by compression, transection, infiltration, ischemia, or metabolic injury. Common features of neuropathic pain conditions include: descriptors such as burning, shooting, electric, or tingling; motor findings of spasms, dystonia, and tremor; and autonomic disturbances of erythema, mottling, and increased sweating.50

There are many reasons to consider neuropathic pain in children with NI. Experience shows that a nocioceptive pain source may not be identified or pain may continue despite treatment of an identified source. “Screaming of unknown origin” was used to describe children with neurologic disorders, severe developmental delay, neurodegeneration, or severe motor impairments with persistent agitation, distress, or screaming, acknowledging that evaluation often does not identify a specific nociceptive cause.52 Pain in children with NI is typically thought to be nociceptive in origin; however, after repeated injury or surgery, neuropathic pain may also occur.53 In one case series, 6 children with cerebral palsy developed neuropathic pain following multilevel orthopedic surgery.54 Onset of symptoms ranged from 5 to 9 days. Interventions included gabapentin in 4 children, amitriptyline in 2, and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for 5, with improvement in symptoms over variable periods of time. Although not reported, experience in nonverbal children with NI identifies development of crying spells increasing in intensity weeks to months following major surgery, such as for neuromuscular scoliosis. Medications used for neuropathic pain include opioids, tricyclic antidepressants such as nortriptyline and amitriptyline, and anticonvulsants such as gabapentin, pregabalin, carbamazepine, phenytoin, valproic acid, and lamotrigine.50

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree