63 Nephrotic Syndrome

Etiology and Pathogenesis

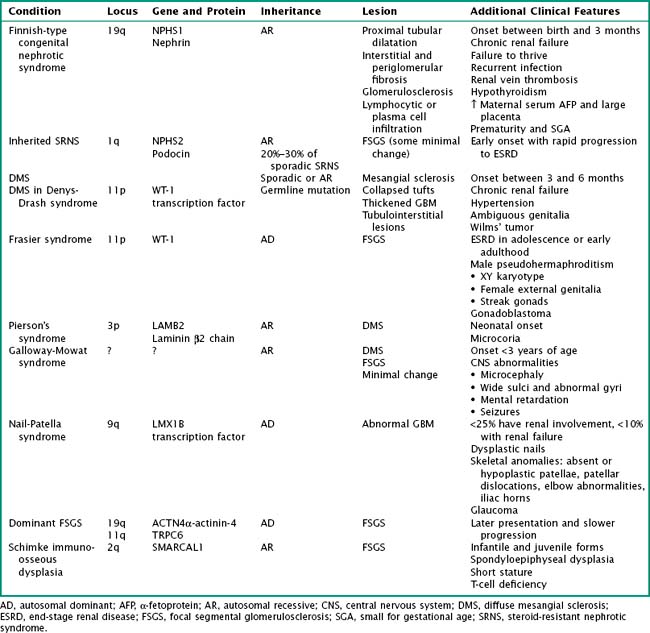

Although most often idiopathic, a variety of conditions and agents are associated with the nephrotic syndrome. These include (1) infections (e.g., HIV, hepatitis B and C, syphilis, toxoplasmosis, malaria), (2) drugs or toxins (e.g., nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, lithium, ampicillin, penicillamine, heroin, mercury), (3) malignancy (lymphoma, leukemia), (4) allergens (e.g., certain foods and bee stings), and (5) obesity. Nephrotic syndrome may also be an associated feature of several glomerulonephritides, such as lupus nephritis, membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN), and immunoglobulin A (IgA) nephropathy. With advances in molecular biology, there has been increasing discovery of genetic disorders resulting in steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome (Table 63-1). The clinical course and histopathology depend on the underlying disease process or precipitating factors.

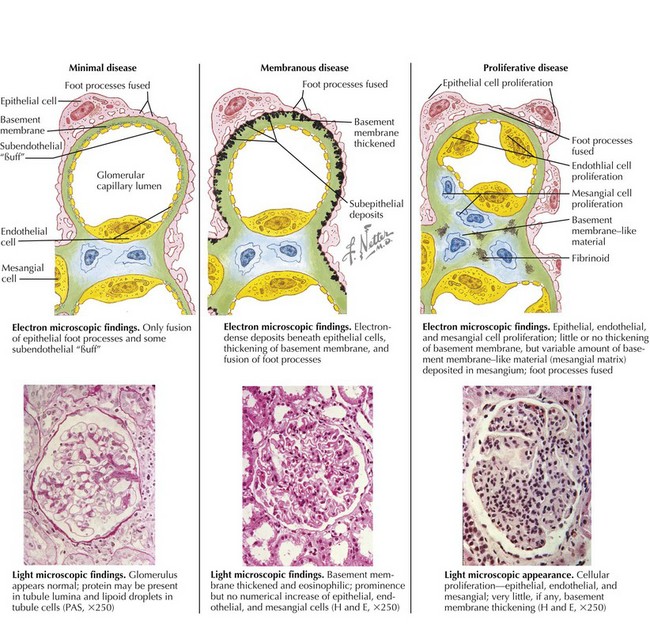

Although the pathophysiologic mechanisms responsible for nephrotic syndrome clearly involve both environmental and genetic factors and differ based on the underlying diagnosis, the unifying pathology is damage to the glomerular filtration barrier either through injury to the glomerular basement membrane (GBM) or podocytes. On electron microscopy, there is effacement, retraction, and vacuolization of epithelial foot processes, and in the unique case of membranous nephropathy, there are immune complex deposits. Light microscopy may show no abnormalities (minimal change), mesangial proliferation or matrix expansion, any of several morphologic variants of focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), or thickening of the GBM (membranous). Immunofluorescent staining results are typically negative in MCNS. There are characteristic patterns of staining in FSGS and membranous nephropathy as well as in the primary glomerulonephritides associated with nephrotic syndrome, such as lupus and MPGN (Figure 63-1). Although the histopathology is important, particularly if there is significant tubulointerstitial fibrosis and glomerulosclerosis, the response to steroid therapy is the most important predictor of clinical outcome.

Clinical Presentation

Edema

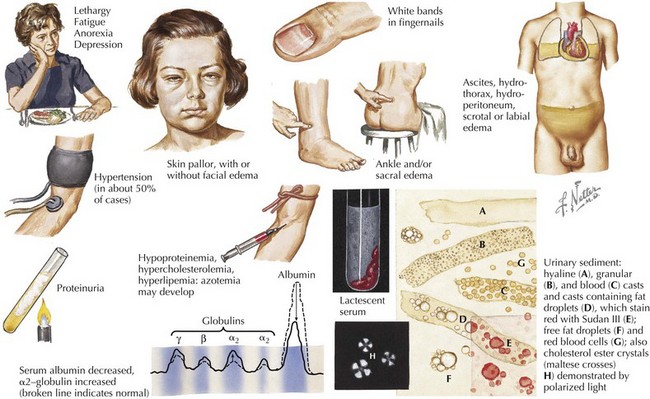

Edema is the main presenting feature, and its onset may be rapid or insidious. Edema is detectable when fluid accumulation is greater than 3% to 5% of body weight. Edema often presents in the periorbital region, is more pronounced in the morning, and is often misdiagnosed and treated as an allergic reaction or seasonal allergies. Edema may fluctuate with positional changes and activity, with lower extremity swelling being more noticeable over the course of the day. Edema develops in other dependent areas such as the sacral region and genitalia. Pleural effusions are generally asymptomatic but if large may cause respiratory compromise. Ascites may lead to umbilical or inguinal hernias as well as to more serious complications, such as spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP). Bowel wall edema may produce diminished appetite; abdominal colic; and diarrhea, which, if chronic, can lead to a protein-losing enteropathy. Skin breakdown and infection can occur in the setting of severe edema (Figure 63-2).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree