18.1 Gestational Trophoblastic Disease

EXPLANATION OF CONDITION

Gestational trophoblastic disease (GTD) is a spectrum of pregnancy related tumours arising from trophoblastic proliferative disorders without a viable fetus. At the benign end of the disease spectrum there is hydatidiform mole and at the malignant end of this continuum spectrum there is the metastatic gestational trophoblastic neoplasia (GTN).

- Complete hydatidiform mole (CM) – is associated with a chromosomal anomaly. This is often diploid and androgenetic in origin. This condition develops from abnormal fertilisation and abnormal development of the placental tissue. It presents as a collection of fluid-filled cysts that develop when the chorion surrounding the embryo degenerates in early pregnancy

- Partial hydatidiform mole (PM) – they are usually paternally derived triploid conceptions in which embryonal development occurs in association with trophoblastic hyperplasia

- Choriocarcinoma – this is an invasive hydatidiform mole that has the potential to metastasise

- Placental site trophoblastic tumours – only complete hydatidiform mole have been shown to develop into tumours. These are extremely rare but have a variable prognosis

Risk factors:

- Increased maternal age2

- Previous hydatidiform mole3

- Grand multiparas3

- Ethnicity (women from Asia have a higher incidence)4

- Socioeconomic status2

- Environmental exposure3

COMPLICATIONS

Abnormal trophoblastic tissue is commonly associated with vaginal bleeding, particularly in the first trimester5. The medical history and examination often reveals an excessive nausea and vomiting (hyperemesis gravidarum) associated with an abnormally high beta human chorionic gonadotrophin (βhCG) level and a uterus which is larger than expected for the gestational age. Other associated complications may include anaemia, thromboembolism or hyperthyroidism, but these are less commonly seen, especially in developed countries because there is widespread use of sensitive pregnancy tests and early diagnosis of pregnancy and viability by high quality ultrasound. However, early onset of pre-elampsia in the second trimester is a recognised presentation in developing countries in particular where access to these facilities is limited.

With the availability of ultrasonography and in particular transvaginal sonography in the first trimester6 such abnormalities can usually be confirmed. However, the diagnosis of complete hydatidiform moles is more reliable ultrasonographically than diagnosing partial moles as this can be more complex1. Approximately 50% of women with an abnormal ultrasound scan will have a hydatidiform mole confirmed by histology7.

Molar pregnancy recurs in about 1 in 80 subsequent pregnancies8.

TREATMENT AND CARE

Suction curettage is the preferred method of evacuation regardless of the size of the uterus in women, who desire to preserve their fertility9, and precautions need to be taken against massive blood loss. A second evacuation is not usually required unless the woman has persistent bleeding and ultrasound shows significant abnormal residual tissue. The avoidance of oxytocic agents should be considered due to speculative risk of causing disseminated trophoblastic disease. Histological examination of the products of conception is recommended in both the cases where a diagnosis of GTD is suspected but also from medical or surgical management of all failed pregnancies1.

Hysterectomy is a reasonable option for women who do not wish to preserve their fertility10. However, women should be counselled that although this procedure stops the risk of local invasion, it does not eliminate the possible need for chemotherapy or the need for monitoring of βhCG concentrations after the procedure.

All women in the UK with GTD should be registered with the Trophoblastic Disease Registration and Surveillance scheme11. Women are followed up with serial serum and urinary βhCG levels to identify those women with persistent trophoblastic tissue either localised to the uterus or disseminated elsewhere such as in choriocarcinoma. This tissue is highly sensitive to chemotherapy with high rates of remission expected.

Chemotherapy is the treatment of choice especially for choriocarcinoma. The need for chemotherapy following a complete mole is 15% and after a partial mole is 0.5%12. Treatment is used based on the International Federation of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (FIGO) scoring system13.

Women who receive chemotherapy treatment for choriocarcinoma are likely to have an earlier menopause and are at risk of developing secondary cancers if their choriocarcinoma is classified as high risk1.

Psychological support is important for women with a diagnosis of GTD as this can have a profound effect on a woman and therefore when discussing the management and care required it is also essential to acknowledge this disease is associated with not only the loss of a pregnancy but also the concerns regarding malignancy14. Women may experience feelings of anxiety, anger, confusion, sexual dysfunction and concerns for future pregnancies10.

PRE-CONCEPTION ISSUES AND CARE

The risk to women of having a further molar pregnancy is relatively low at a rate of 1 in 801. If a further molar pregnancy occurs it is usually of the same histological type8. Women are advised to avoid conception while they are on active follow-up because the monitoring process relies on the use of βhCG levels to detect persistent trophoblastic disease. Obviously if a further pregnancy occurs the βhCG levels will rise, causing confusion in the follow-up process.

Both early pregnancy and hormonal contraception may increase the risk of persistent trophoblastic disease and choriocarcinoma so effective use of barrier methods of contraception is recommended1.

- Pregnancy viability can be determined using a combination of ultrasound (transvaginal) and serial βhCG levels for management of first trimester bleeding15

- Significant fetomaternal haemorrhage may occur following an early pregnancy loss or threatened miscarriage of a viable fetus. In this situation rhesus negative women should have anti-D immunoglobulin administered to reduce the risk of iso-immunisation

- Obviously a twin pregnancy that is affected by GTD will be classified as high risk and a multidisciplinary approach will be taken

- It is important to be alert to the signs and symptoms of GTD but at the same time be mindful that such symptoms could be related to a multiple pregnancy

- The majority of pregnancies following a molar pregnancy can be managed as low risk under the care of community midwifery.

- Accurate record keeping is essential to make sure subsequent pregnancies are observed closely with a referral mechanism if required

- If a subsequent pregnancy has continued uneventfully to term after a molar pregnancy it is not necessary for obstetric input into the labour provided progress and fetal monitoring are satisfactory17.

- Normal midwifery care in labour is appropriate following a molar pregnancy

- The placenta and membranes should be sent for histological assessment after birth to rule out evidence of GTD

- The regional Trophoblastic Disease Screening Centre should be informed of the fact that a woman who has previously been registered with them has delivered so they may organise for her to provide postnatal urine samples for βhCG concentrations to rule out any recurrence of the disease11

- If there is any suspicion of recurrent GTD the obstetric team should liaise appropriately with the regional Trophoblastic Disease Screening Centre17

- Appropriate contraceptive advice should be offered with avoidance of hormonal contraception and utilisation of barrier contraception encouraged until βhCG levels are within normal limits

- To provide information regarding contraception and refer to the woman’s GP

- Normal postnatal care should be provided with careful monitoring of uterine involution and lochia as poor involution and excessive lochia or irregular bleeding could indicate evidence of GTD

- Women may require extra support if there is a need to attend the regional Trophoblastic Disease Screening Centre if serial βhCG levels are not returning to normal at an appropriate rate

18.2 Cervical Cancer

EXPLANATION OF CONDITION

Cervical cancer is the eleventh most common cancer in women in the UK and the third most common gynaecological cancer1. In the UK it is rare for young women to die from cervical cancer; over 80% of all cervical cancer deaths are women over 45 years old. Incidence has almost halved in the last 20 years1. However, mortality rates increase with age, with the highest number of deaths occurring over 75. Less than 6% of cervical deaths occur in women under 351.

Types

Cervical cancer is malignant neoplasm of the cervix uteri or cervical area. There are two main types:

- Squamous cell cancer

- Adenocarcinoma2

The most common type of cervical cancer, squamous cell cancer, arises in the squamous cells covering the outer surface of the cervix whilst adenocarcinoma arises in the glandular cells which are normally in the cervical canal. While the overall incidence of cervical cancer is falling in the UK as a result of an effective screening programme, adenocarcinoma is becoming relatively more common. Cervical cancer if left untreated invades the normal tissue of the cervix, the tissues around the cervix and vagina, the body of the uterus, the bladder towards the front and the rectum behind. If the tumour is allowed to grow to the pelvic side wall it will obstruct the ureters causing hydronephrosis and obstructive renal failure. The more extensive the tumour the greater is the chance the lymph glands in the pelvis and para-aortic chain will be involved with metastatic cancer.

Symptoms

Cervical cancer is often asymptomatic at an early stage and detected when women attend the colposcopy service with an abnormal smear. Most of these women can have local treatment to the cervix which is curative. As cervical cancer becomes more established abnormal vaginal bleeding such as post-coital bleeding (bleeding after intercourse), intermenstrual bleeding (unprovoked bleeding between periods) or postmenopausal bleeding is common3,4.

Other symptoms may include an offensive vaginal discharge or discomfort or pain during sex. However, both of these symptoms are more likely to be due to other causes not related to cancer.

In advanced cervical cancer there may be symptoms of systemic malaise such as tiredness, lethargy and nausea. This may be related to obstructive renal failure causing uraemia and electrolyte disturbances.

Human papillomavirus (HPV)

Oncogenic (cancer forming) human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is believed to be the cause of both invasive cervical cancer and the premalignant change in the cervical epithelium (cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, CIN). There are more than 150 types of HPV acknowledged to exist although not all of these predispose to cervical cancer2. Some HPVs cause benign skin warts or papillomas, which is the origin of the name of the virus.

There are approximately 40 types that affect the genital area and these are sub-divided into two groups; low risk and high risk cervical cancer. Low risk types are responsible for genital warts (serotype HPV-6 and HPV-11) and high risk types occurring most frequently in cervical cancer are mainly serotypes HPV-16 and HPV-18. Together these account for over 70% of squamous cell cervical cancers3. HPV-18 is also thought to account for approximately 50% of all adenocarinomas2.

HPV is transmitted sexually but is not considered a sexually transmitted disease so women who have been treated for CIN or cervical cancer should not feel stigmatised. Eighty percent of sexually active people will show serological evidence of exposure to oncogenic HPV during their lifetimes but it is believed that it is only those individuals who have persistent infection who develop CIN and then cervical cancer5. The majority of people exposed to oncogenic HPV just have a transient infection which does not cause long-term harm. It is reassuring that there is a long latent period between exposure to oncogenic HPV and developing cervical cancer. Because most infections are transient cervical screening (Figure 18.2.1 and Table 18.2.1) is not recommended in England before the age of 25 years as it is expected this will reduce the incidence of treatment in young women who would otherwise have reverted back to normality spontaneously.

Clearly, factors which affect the immune response are critical to the development of CIN and cervical cancer. Smoking is associated with increased risk in the development of premalignant and malignant changes in the cervix, although it is unclear as to which compounds in cigarette smoke are actually responsible for this action. A number of prescribed drugs, including long-term use of steroids for various autoimmune diseases or immunosuppressive drugs administered in transplantation patients, are associated with an increased risk of CIN and cervical cancer. Systemic illness such as HIV infection causes immunosuppression and increases the risk of cervical cancer. This link is so well established that diagnosis of cervical cancer in an HIV-positive patient is considered to be an AIDS defining condition.

There appears to be other factors that could also increase the risk of cervical cancer:

- Experiencing sexual intercourse from an early age

- Multiple sexual partners

- Having intercourse with a male partner who has had multiple sexual partners

- Oral contraceptive pill for more than 4 years has a theoretical link6

Staging

Staging is by the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO)7. This is based on clinical findings rather than surgical findings. Once cervical cancer has been identified it is then divided into stages.

A broad overview is below:

- Stage I – Carcinoma is strictly confined to the cervix

- Stage II – Carcinoma invades beyond the cervix into the immediate surrounding tissues including the upper two-thirds of the vagina

- Stage III – Carcinoma extends to the pelvic wall and involves the lower third of the vagina

- Stage IV – Carcinoma extends beyond the pelvis with involvement of the bladder and rectum, or more distant organs such as the lungs

NON-PREGNANCY TREATMENT AND CARE

Treatment for Abnormal Cells

There are several different treatments for pre-cancerous/abnormal changes (CIN) in the cervix. They all aim to remove or destroy abnormal cells. This can be done by freezing (cryotherapy), with heat from a laser (laser ablation) or a hot probe (cold coagulation – this is a misnomer, the probe is regulated to 140 °C), or by treating the abnormal area with electric cautery. Either electric diathermy may be used to ablate an area or a large loop excision of the transformation zone (LLETZ) may be used with electric cautery. This later technique has the benefit of providing a sample of tissue which can be sent for histological assessment to confirm the exact nature of the lesion.

Treatment for Cervical Cancer

Stage 1a cervical cancer (microinvasive disease) is mostly treated with local excision of the lesion from the cervix which, provided there is evidence of normal tissue from around the area of invasive disease, should not require further treatment. To rule out evidence of early spread of disease full cancer staging is performed with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and examination under anaesthetic in most cancer centres. These women retain normal fertility but may be at increased risk of pre-term birth in pregnancy.

Clinically visible cancers confined to the cervix (stage Ib) mostly require more extensive treatment. The risks of lymph node metastases increases with the grade of tumour and size of the primary. Patients who have lymph node metastases diagnosed on MRI, laparoscopic lymph node sampling or after radical surgery are recommended to have combination treatment with chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Those women who are lymph node negative who wish to retain fertility with small cervical cancers may be offered a radical trachelectomy operation. The cervix is resected with the surrounding tissues, including a cuff of vagina, and pelvic lymphadenectomy is performed. The body of the uterus is retained and an artificial cervix is created with a permanent non-absorbable suture inserted in the base of the body of the uterus. For women not wishing to retain fertility or those with larger tumours either confined to the cervix or just extending outside the cervix into the surrounding tissues or vagina (stage IIa) the standard treatment is radical hysterectomy with pelvic lymphadenectomy. The benefit of this over combination treatment with chemotherapy and radiotherapy in premenopausal women is the women can retain their ovaries. They will remain premenopausal and could potentially provide eggs for IVF and a surrogacy program if they wished to have a baby in the future which is of their own biological make up. For women with more advanced disease, combination treatment with chemotherapy and radiotherapy is recommended but this treatment renders premenopausal women infertile, postmenopausal and with a high incidence of sexual dysfunction due to vaginal narrowing and dryness.

PRE-CONCEPTION ISSUES AND CARE

Pre-invasive abnormalities (CIN) should not preclude a pregnancy but repeated treatments put the woman at risk of pre-term birth. If there has been conservative fertility sparing treatment for early cervical cancer, pregnancy is possible but again the women should be counselled to the risks of premature labour.

Pregnancy is not an option for women who have undergone a hysterectomy or radiotherapy for invasive cervical cancer. If the ovaries have been retained and the woman remains premenopausal ovulation induction for an IVF cycle and surrogacy could be possible.

- Women with cervical cancer during pregnancy often present with vaginal bleeding. Despite vaginal bleeding usually being associated with pregnancy, this should not be presumed and cancer should be considered a possibility

- If there are any early stages of cervical cancer, these can be treated in the form of a suitably tailored cone biopsy. Although LLETZ is a more conservative method it has been shown to cause less complications8

- Colposcopic and cytological surveillance of cervical lesions during pregnancy appears to be safe in pregnancy

- If the tumour is at an advanced stage, radical surgery, chemotherapy or radiotherapy may need to be considered. Therefore this will depend on the stage of the disease and gestation, and appropriate delivery considered

- A detailed medical and obstetric history should be documented

- On vaginal examination ensure the cervix and vagina can be visualised to identify any abnormalities

- Cervical cytology is not usually performed in pregnancy, unless there are specific reasons such as a ‘poor attender’ in which case they might be performed up to 12 weeks gestation

- If confirmed vaginal bleeding consider anti-D prophylaxis in cases of Rhesus negative women beyond 10 weeks gestation

- Cervical cerclage to prolong the pregnancy may be necessary if there is evidence of cervical shortening on serial cervical length measurements

- If possible delay any treatment until after 32 weeks to minimise the risk of prematurity

- Ensure a thorough booking history, that identifies past or present gynaecological symptoms and treatment, and a referral should be made for obstetric review

- In the event of vaginal bleeding this should warrant referral for a medical examination and review

- Women who feel stigmatised by the link between sexual activity and cervical cancer should be supported, counselled and educated to the reality of risk of exposure of oncogenic HPV in our society

- Vaginal delivery is possible if CIN is under surveillance, but there is a higher risk of haemorrhage if there is a cervical tumour9. There is also risk of cervical dystocia due to scar tissue, and caesarean section may be necessary for failure to progress in labour

- In cases of advanced cancer, which are rare in pregnancy, a caesarean-radical hysterectomy may be necessary. At the time of surgery the ovaries may be preserved

- Active monitoring of progress in labour is important as cervical dystocia may cause poor progress in labour. Augmented labour in this situation with oxytoxic drugs could increase the risk of uterine rupture

- Obstetrician and oncology team should consider timing and type of caesarean section. A classical caesarean section under certain circumstances would minimise the risk of disturbing the tumour; this could be followed by a radical hysterectomy or combination treatment with chemotherapy and radiotherapy depending on the stage of disease

- A multidisciplinary approach is imperative in the woman’s care

- In cases of CIN only, the labour can be managed normally by the midwife if vaginal delivery is anticipated

- Be aware that slow progress in the first stage of labour could be due to cervical dystocia, hence regular assessment of the progress of labour should be made with judicious completion of the partogram

- Be alert for intra-partum bleeding, particularly in established labour

- There should be an increased awareness that a cervical lesion could be the cause of postpartum haemorrhage particularly if the uterus is found to be well contracted

- The puerperium could be a period of anxiety, as the woman may have concerns about future cancer treatment and prognosis. There may be relationship tensions if the woman has experienced post-coital bleeding or feels traumatised

- In pregnancy and puerperium the cervical cytology (if they were deemed necessary) should be interpreted and evaluated as in a non-pregnant state10

- Contraception is advised and prescribed as normal

- Seen within 3 months post-delivery

- Review every 3 months for 1 year post-treatment

- Review every 4 months for second year post-treatment

- Review every 6 months for third, fourth and fifth year post treatment

- Women should be informed about the potential impact of cervical procedures on future pregnancies/fertility

- After the treatment of a caesarean-radical hysterectomy women will need to be seen at regular intervals by the oncology team. Complex management is necessary, which cannot be addressed within the confines of this textbook and further sources should be consulted

- Normal postpartum care, being alert for secondary postpartum haemorrhage

- Midwifery care of any surgical procedures as above

- Observe blood loss

- Encourage and support the woman to attend follow-up appointments

- Consider thrombo-prophylaxis

18.3 Cervical Screening

EXPLANATION OF SCREENING

Cervical cancer is preventable and curable if detected in its pre-malignant stage or at an early stage of invasive disease2. Cervical screening does not test for cancer but, using cervical cytology, detects pre-malignant changes which, if untreated, could lead to cervical cancer. Women who have abnormal cells identified are referred to the colposcopy service for further assessment and if necessary treatment (Figure 18.2.1). HPV is transmitted through sexual activity but is not considered a traditional sexually transmitted disease because 80% of people have serological evidence of exposure to the virus. Persistent infection can result in cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) a premalignant condition which over a long latent period may progress to invasive carcinoma. Primary prevention is aimed at prophylactic vaccines against high risk HPV3.

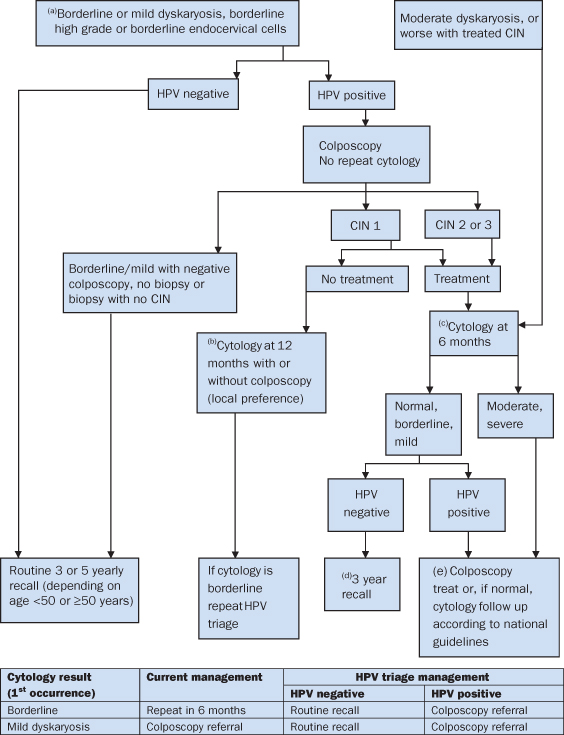

Figure 18.2.1 Human papilloma virus (HPV) triage and test protocol for women aged 25–64 years (reproduced with kind permission from the NHS Cancer Screening programme, August 2011. This algorithm may be updated at regular intervals, so check the NHSCSP website). (a) If sample is unreliable/inadequate for the HPV test, refer mild and recall borderline for 6 month repeat cytology. At repeat cytology HPV test if negative/borderline/mild. If HPV negative return to routine recall: if HPV positive, refer. Refer moderate or worse cytology. (b) Follow up of 12 month cytology only should follow normal NHSCSP protocols. (c) Women in annual follow up after treatment for CIN are eligible for the HPV test of cure at their next screening test. (d) Women >50 who have normal cytology at 3 years will then return to 5 yearly routine recall. Women who reach 65 must still complete the protocol and otherwise comply with national guidance. (e) Women referred owing to borderline or mild or normal cytology who are HR-HPV positive and who then have a satisfactory and negative colposcopy can be recalled in 3 years.

This figure is downloadable from the book companion website at www.wiley.com/go/robson

The UK NHS Cancer Screening Programme4 announced it would introduce human HPV testing in 2012 to supplement the existing cervical cytology testing. The benefit is that those women with low grade cytological abnormalities, if found to be negative for oncogenic HPV, may return to routine cytology screening. Previously they would have attended colposcopy services for repeat assessments until cervical cytology returned to normality. This new development is based on evidence resulting from extensive research and assessment into the utility of HPV testing4.

For any screening programme to be successful it relies on the targeted population to respond to an invitation to be screened. In the case of the cervical screening programme there is a long latent phase which lends itself to repeated opportunities for the pre-malignant changes to be detected and acted upon. Through a combination of public awareness campaigns and support from primary health care providers there has been a high uptake of screening in eligible women. This has facilitated the success of a screening programme reducing overall morbidity and mortality in the general population.

Despite HPV being common within the first 10 years5 of women becoming sexually active, the NHS in England raised the age of commencement of screening from 21 to 25 years6 to acknowledge the long latent phase between HPV infection and development of cervical cancer. Many will have a transient infection with associated changes on the cervix (CIN) which in many cases resolves spontaneously. The delay in commencement of screening will reduce the number of colposcopy treatments in this group reducing potential morbidity relating to cervical incompetence and pre-term labour.

The Process of Cervical Sampling

The cervical screening programme consists of a cytopathological examination of a cell sample taken from the cervix. Liquid-based cytology (LBC) is a relatively new way of preparing cervical samples for examination in the laboratory. The original technique described by Papanicolaou used a wooden spatula to sample cells on the cervix which were smeared onto a microscopic slide. Liquid-based cytology uses a specially designed brush to sample cells from the cervix. The head of the brush, where the cells are lodged from the sampling, is detached and placed into a small vial containing preservative fluid. The sample is sent to the laboratory where the cells are re-suspended. A sample of the fluid is used to prepare a glass slide. This method provides a more even preparation of cells which can be stained and assessed by the cytologist. This method is superior to the original technique because the fixation process causes the red blood cells to lyse reducing the chance of the sample being unsuitable for assessment. The cellular preparation is more uniform with less cellular grouping, lending itself to easier and more accurate assessment and potentially more automated assessments.

Cervical cytology is used to identify abnormal or dyskaryotic cervical cells which may indicate the presence of CIN, an established precursor for cervical cancer. Women who have abnormal cervical cytology are requested to attend the colposcopy service where any areas of abnormality can be further assessed and if necessary treated. Any tissue removed is sent for histological assessment to confirm the presence of CIN and to identify any evidence of invasive cancerous disease. Although not all CIN progresses to invasive cancer, persistent mild abnormalities increase the risk of developing cervical cancer in later life7.

The Statistics

NHS cervical screening statistics1 for 2010–2011 indicate that in almost 98% of cases English women are receiving results more quickly than before. However, only 79% of eligible women were screened, indicating that 21% of women are unscreened.

Effectiveness of a screening programme is the percentage of women in the target group who have been screened in the last 3 years (under 50s) or 5 years (under 50–64 years old). The NHS Screening Programme Annual Review 2010–20111 states ‘the overall number of 3 351 127 women taking part has increased by over 70 000 compared with 2009–2010’. However, this number is still lower than the figure in 2008–2009 which reached a peak of 3 607 373 due to the high profile of celebrity Jade Goody’s death. Table 18.2.1 illustrates the results of adequate tests for women aged 25–64 years (2010–2011)8.

Table 18.2.1 NHS Cervical Screening Programme: percentage of tests in the year by type of invitation and result, 2010–2011 (all ages)

| Result | Percentage |

| Inadequate | 2.8 |

| Negative | 90.0 |

| Borderline changes | 3.9 |

| Mild dyskaryosis | 2.1 |

| Moderate dyskaryosis | 0.5 |

| Severe dyskaryosis | 0.6 |

| ?Invasive carcinoma | 0.0 |

| ?Glandular neoplasia | 0.1 |

NON-PREGNANCY AND PRE-CONCEPTION CARE

- A primary prevention programme involves HPV vaccination for two groups, all 12–13-year-old girls (ideally before they are sexually active) and a ‘catch-up’ group of 17–18-year-old girls. This later group will be discontinued when the vaccinated 12–13-year-old girls reach 17–18 years. This caused controversy with issues of parental consent. Gillick competence was raised, and some groups complaining this promotes a promiscuous society

- UK eligibility for NHS cervical screening is:

| Age Group (Years) | Frequency of Screening |

| 25 | First invitation |

| 25–49 | 3 yearly |

| 50–64 | 5 yearly |

| 65+ | Those who have not been screened since 50 years or have had recent abnormal tests |

If a woman is planning to become pregnant, her GP should check that her cervical screening is up to date, to enable pre-pregnancy treatment.

- Mechanisms that compromise cervical function such as cervical excisional procedures may be associated with cervical incompetence and adverse pregnancy outcomes9

- Pregnancy after cervical surgery has a theoretical risk of a pre-term birth, but the risk only becomes significant if more than one excisional treatment has been performed

- Women who have CIN in pregnancy have a very low risk of progression to cancer during the pregnancy so a conservative approach is usually agreed with surveillance followed by any necessary treatment approximately 12 weeks post-delivery

- Only if there is a very high suspicion of invasive cancer would a biopsy be considered because during pregnancy there is a risk of haemorrhage and infection with a small chance of miscarriage or pre-term birth10

- Cervical cerclage is still an option if cervical incompetence has been demonstrated usually by serial cervical length measurement by ultrasound

- Counselling of women who require cervical procedures must include the risks and benefits of ablative and excisional methods

- Accurate dating of the pregnancy is important as this information may be critical later in the pregnancy in the decision-making process

- A thorough booking history is taken and a referral is made to be delivered within a consultant lead unit

- Midwifery support ideally in a specialist pre-term birth clinic is essential as many women who have had more than one colposcopy treatment are very anxious about the risks of pre-term birth during the antenatal period

- If CIN has been diagnosed in pregnancy this should not significantly affect labour

- If cervical cancer has been diagnosed in pregnancy early, and is believed to be at an early stage without lymphovascular invasion a vaginal delivery is acceptable with therapeutic conisation in the postpartum period

- If the stage is IB1 or IB2 a caesarean-radical hysterectomy should be considered or caesarean followed by chemoradiotherapy

- A caesarean section is the preferred route of delivery to prevent fatal recurrences in the episiotomy scar11 and catastrophic life threatening haemorrhage

- To develop a plan of management and treatment in respect of cervical findings

- Establish a multidisciplinary team approach

- Ensure there is good communication between all disciplines

- Discuss birth plan and provide optimal care as previous cervical treatment may affect the ability of the cervix to dilate in labour

- Obstetric team to liaise with the oncology team if required

- Patients who have been diagnosed with CIN should have further colposcopy and possible further treatment but not before 3 months postpartum

- Normal midwifery postpartum care

- Organise any follow-up appointments, explaining the benefits of screening and prompt commencement of treatment if required

18.4 Breast Cancer

EXPLANATION OF CONDITION

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women and is the leading cause of death in women aged between 35 and 54 years. Fifteen percent of cases are diagnosed before the age of 45 years and therefore this affects almost 5000 women of child-bearing age.

Pregnancy associated breast cancer is defined as a carcinoma that is diagnosed during pregnancy or within one year postpartum. The median age of these women is 33 years, ranging from 23 to 47 years3.

Pregnant women are at a higher risk of presenting with more advanced disease than non-pregnant women as small lumps cannot be detected as well due to natural tenderness and engorgement of the breasts during pregnancy and lactation.

Most women present with painless masses, with up to 90% of cases being detected by self-examination. Other symptoms may be enlarging masses, nipple or skin retraction, other skin changes or axillary lymphadenopathy.

Screening by mammography detects around 68% of cancerous changes but this can be challenging in pregnancy. The use of ultrasound can detect around 93% of changes in pregnant women.

Diagnosis may be confirmed by using fine needle aspiration under local anaesthesia. However, the normal hyperplastic epithelial changes in breast tissue during pregnancy make interpretation of the specimen more difficult requiring a pathologist with particular expertise to make an accurate assessment.

In the absence of a positive fine needle aspiration a diagnostic excisional biopsy with either general or local anaesthetic is performed. Once a diagnosis of cancer is confirmed an assessment of stage of the disease is required.

Breast Cancer Stage Grouping4

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree