106 Neonatal Resuscitation

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Fetal Circulation

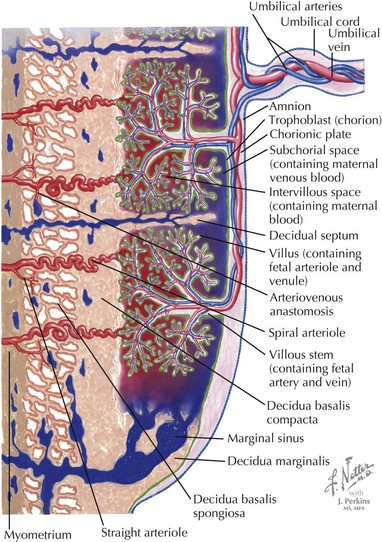

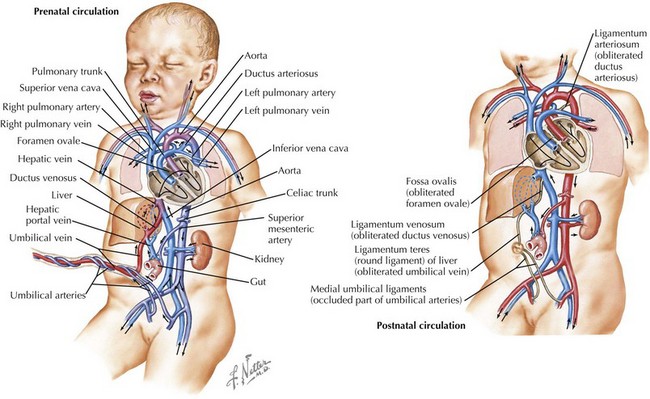

In fetuses, the placenta performs the primary gas exchange function rather than the lungs, and several circulatory adaptations exist to facilitate flow of oxygenated blood through the body and placenta. Deoxygenated blood from the body of the fetus flows to the placenta via the umbilical artery and becomes oxygenated through gas exchange with maternal blood. The oxygenated blood then flows back to the fetus via the umbilical vein (Figure 106-1). The umbilical vein deposits the blood to the inferior vena cava via the ductus venosus, which subsequently delivers it to the right atrium of the heart. In the right atrium, the blood partially mixes with blood from the superior vena cava, and the majority of it streams across the foramen ovale to the left atrium because of the high pulmonary vascular resistance. From the left atrium, blood flows through the left ventricle to the aorta, thereby delivering the most oxygenated blood to the brain via the carotid arteries. The remaining blood in the right atrium, largely from the superior vena cava, flows into the right ventricle and then into the pulmonary artery. A small amount of blood perfuses the lungs and then travels to the left atrium via the pulmonary veins. Most of the blood, however, is diverted across the ductus arteriosus to the descending aorta, where it joins the blood from the left ventricle. From the aorta, the blood is distributed via branches off the aorta and ultimately reaches the umbilical artery and the low pressure placenta again (Figure 106-2).

Transition to Neonatal Circulation

This system changes dramatically when the infant is born. Because of the stress of labor and delivery, the baby experiences a catecholamine surge at birth. Catecholamines regulate fluid resorption in the lungs, surfactant release into the alveoli, temperature, glucose mobilization, and blood flow to the brain and vital organs. When the umbilical cord is clamped, the placenta is removed from the circulation, causing a large increase in systemic vascular resistance. When the infant takes his or her first breath, the pulmonary vascular resistance decreases precipitously, causing blood to travel through the right atrium to the right ventricle and then the lungs rather than through the foramen ovale to the left atrium. The lower pulmonary pressures also result in less blood flow across the ductus arteriosus and more flow from the pulmonary artery to the lungs. The ductus venosus, ductus arteriosus, and umbilical vessels eventually constrict, leaving the infant with a fully intact neonatal circulatory system (see Figure 106-2). The initial breaths taken by the infant also must inflate the lungs and effect a change in vascular pressures so lung water is absorbed into the pulmonary arterial system and cleared from the lung.

Asphyxia

In some cases, the fetal reserve is not enough to protect the infant from difficulties with transition. Neonatal asphyxia can result from multiple factors, both maternal and fetal (Table 106-1), and may begin in utero. The initial response to asphyxia is a brief period of rapid breathing followed by “primary apnea.” During primary apnea, stimulation such as drying or slapping the feet will restart breathing. If the apnea is prolonged, the infant loses muscle tone and becomes cyanotic and then bradycardic. After a few gasping respirations, the neonate enters “secondary apnea.” At this point, ventilatory support must be provided for the newborn to survive. In this situation, an infant requires resuscitative efforts to aid in the transition to extrauterine life.

Table 106-1 Conditions Predisposing to Neonatal Asphyxia

| Maternal | |

|---|---|

| Uterus | Uterine malformations, hypertonus, rupture |

| Infection | Chorioamnionitis |

| Blood | Anemia, hemoglobinopathy |

| Vascular | Diabetes, hypertension, preeclampsia, hypotension |

| Medications Placenta | Narcotics, magnesium Uteroplacental insufficiency, placental abruption, placenta previa, postmature placenta |

| Fetal | |

|---|---|

| Umbilical cord | Compression, prolapse, knot, nuchal cord, thrombosis |

| Blood | Anemia |

| Other | Infection, fetal hydrops, malformations, multiple gestations, inborn error of metabolism |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree