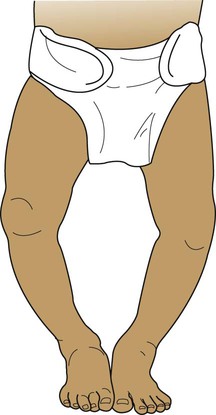

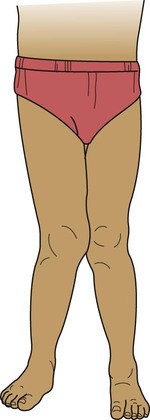

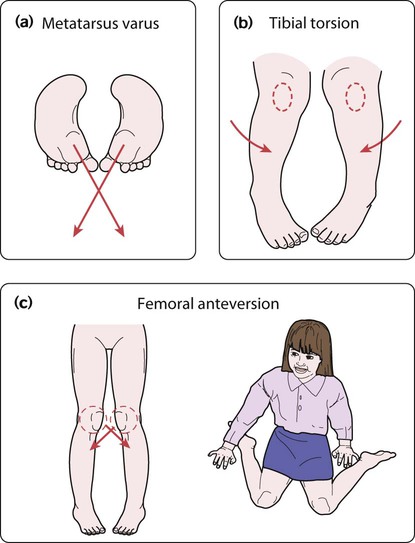

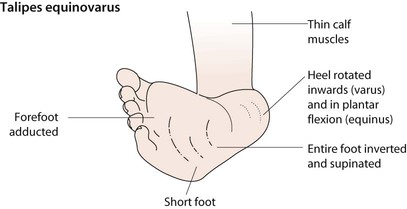

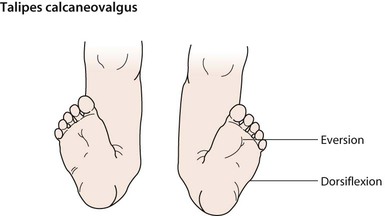

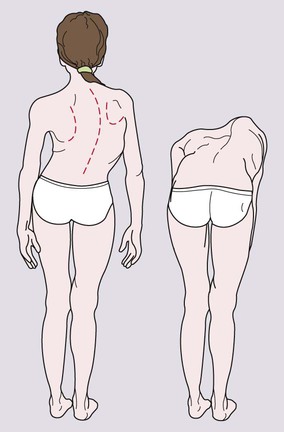

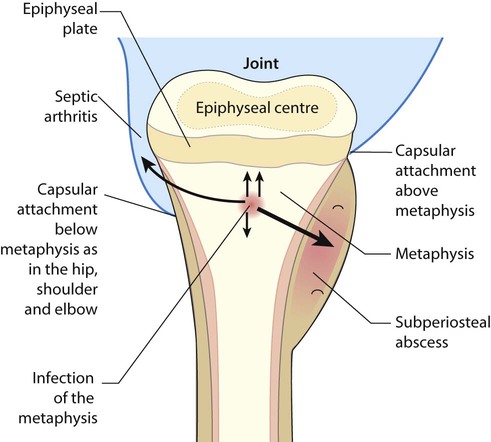

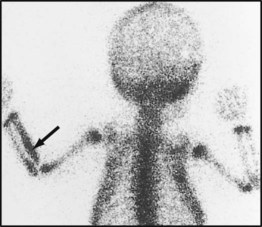

Features of musculoskeletal disorders in children are: • Although musculoskeletal presentations are common and often benign and self-limiting, they can be caused by a serious underlying condition such as infection, malignancy or non-accidental injury • Many concerns of parents about their children’s posture are variations of normal alignment in the growing skeleton • Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is the most common cause of chronic arthritis in children. This should, as a minimum, include the pGALS (paediatric Gait, Arms, Legs, Spine) screen (see p. 25) to identify and localise musculoskeletal problems; any suggestion of a musculoskeletal problem should be followed by more detailed regional musculoskeletal examination (called pREMS, see p. 26). The normal toddler has a broad base gait. Many children evolve leg alignment with initially a degree of bowing of the tibiae, causing the knees to be wide apart – best observed while the child is standing with the feet together (Fig. 26.1). A pathological cause of bow legs is rickets; check for the presence of other clinical features (see Ch. 11). Severe progressive and often unilateral bow legs is a feature of Blount disease (infantile tibia vara), an uncommon condition predominantly seen in Afro-Caribbean children. Radiographs are characteristic with beaking of the proximal medial tibial epiphysis. Toddlers learning to walk usually have flat feet due to flatness of the medial longitudinal arch and the presence of a fat pad which disappears as the child gets older (Fig. 26.3). An arch can usually be demonstrated on standing on tiptoe or by passively extending the big toe. Marked flat feet is common in hypermobility. A fixed flat foot, often painful, presenting in older children, may indicate a congenital tarsal coalition and requires an orthopaedic opinion. Symptomatic flat feet are often helped with footwear advice and, occasionally, an arch support may be required. There are three main causes of in-toeing: • Metatarsus varus (Fig. 26.4a) – an adduction deformity of a highly mobile forefoot • Medial tibial torsion (Fig. 26.4b) – at the lower leg, when the tibia is laterally rotated less than normal in relation to the femur • Persistent anteversion of the femoral neck (Fig. 26.4c) – at the hip, when the femoral neck is twisted forward more than normal. The clinical features are described in Box 26.1. Out-toeing is uncommon but may occur in infants between 6 and 12 months of age. When bilateral, it is often due to lateral rotation of the hips and resolves spontaneously. Talipes equinovarus is a complex abnormality (Figs 26.5, 26.6). The entire foot is inverted and supinated, the forefoot adducted and the heel is rotated inwards and in plantar flexion. The affected foot is shorter and the calf muscles thinner than normal. The position of the foot is fixed, cannot be corrected completely and is often bilateral. The birth prevalence is 1 per 1000 live births, affects predominantly males (2 : 1), can be familial and is usually idiopathic. However, it may also be secondary to oligohydramnios during pregnancy, a feature of a malformation syndrome or of a neuromuscular disorder such as spina bifida. There is an association with developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH). This is a spectrum of disorders ranging from dysplasia to subluxation through to frank dislocation of the hip. Early detection is important as it usually responds to conservative treatment; late diagnosis is usually associated with hip dysplasia, which requires complex treatment often including surgery. Neonatal screening is performed as part of the routine examination of the newborn (see Fig. 9.15), checking if the hip can be dislocated posteriorly out of the acetabulum (Barlow manoeuvre) or can be relocated back into the acetabulum on abduction (Ortolani manoeuvre). These tests are repeated at routine surveillance at 8 weeks of age. Thereafter, presentation of the condition is usually with a limp or abnormal gait. It may be identified from asymmetry of skinfolds around the hip, limited abduction of the hip or shortening of the affected leg. Scoliosis is a lateral curvature in the frontal plane of the spine. • Idiopathic. The most common, either early onset (<5 years old) or, most often, late onset, mainly girls 10–14 years of age during their pubertal growth spurt • Congenital. From a congenital structural defect of the spine, e.g. hemivertebra, spina bifida, syndromes (e.g. VACTERL association – Vertebral, Anorectal, Cardiac, Tracheo-oEsophageal, Renal and Limb anomalies). • Secondary. Related to other disorders such as neuromuscular imbalance (e.g. cerebral palsy, muscular dystrophy); disorders of bone such as neurofibromatosis or of connective tissues such as Marfan syndrome, or leg length discrepancy, e.g. due to arthritis of one knee in JIA. Examination should start with inspection of the child’s back while standing up straight. In mild scoliosis, there may be irregular skin creases and difference in shoulder height. The scoliosis can be identified on examining the child’s back when bent forward (Fig. 26.8). If the scoliosis disappears on forward bending, it is postural although leg lengths should be checked. Older children or adolescents with hypermobility may complain of musculoskeletal pain mainly confined to the lower limbs, often worse after exercise. Joint swelling is usually absent or is transient. Hypermobility may be generalised or limited to peripheral joints (such as hands and feet). There is symmetrical hyperextension of the thumbs and fingers that can be hyperextended onto the forearms (Fig. 26.9), elbows and knees can be hyperextended beyond 10°, and palms can be placed flat on the floor with knees straight. Lower limb findings associated with hypermobility are hyperextensibility of the knee joint and flat feet with normal arches on tiptoe, which are over-pronated secondary to ankle hypermobility. In osteomyelitis, there is infection of the metaphysis of long bones. The most common sites are the distal femur and proximal tibia, but any bone may be affected (Fig. 26.10). It is usually due to haematogenous spread of the pathogen, but may arise by direct spread from an infected wound. The skin is swollen directly over the affected site. Where the joint capsule is inserted distal to the epiphyseal plate, as in the hip, osteomyelitis may spread to cause septic arthritis. Most infections are caused by Staphylococcus aureus, but other pathogens include Streptococcus and Haemophilus influenzae if not immunised. In sickle cell anaemia, there is an increased risk of staphylococcal and salmonella osteomyelitis. Infection may be from tuberculosis; although rare in the UK, it needs to be considered, especially in the immunodeficient child.

Musculoskeletal disorders

Assessment of the musculoskeletal system

Variations of normal posture

Bow legs (genu varum)

Flat feet (pes planus)

In-toeing and out-toeing

Abnormal posture

Talipes equinovarus (clubfoot)

Developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH)

Scoliosis

The painful limb, knee and back

Hypermobility

Acute-onset limb pain

Osteomyelitis

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Musculoskeletal disorders